Analysis: Canada’s banks are outpacing community foundations in launching new donor advised funds. What does it mean for your charity and for the philanthropic sector?

Why It Matters

Donation patterns are changing. Affluent Canadians, whose gifts form a growing share of the overall charitable pie, are increasingly giving through donor advised funds affiliated with banks and wealth management firms.

This journalism is made possible by the Future of Good editorial fellowship covering the social impact world’s rapidly changing funding models, supported by Future of Good, Community Foundations of Canada, and United Way Centraide Canada. See our editorial ethics and standards here.

Last year, in the days leading up to Christmas, Kate Bate sold her design and animation business and decided with her husband to donate a portion of the profits to charity.

The impulse to give wasn’t new for the Toronto couple, who live on the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee, the Huron-Wendat and the Ojibwe-Chippewa people. About five years before, Bate and her husband, Patrick Marshall, co-founded a charity with a group of others, called Together Project, which supports refugees with integration into the community. The pair also regularly give — both when friends ask them to chip in a few bucks for a charity ride and to support organizations working on education and humanitarian causes.

But this time was different. Though the profit from the sale of the business “wasn’t ginormous,” Bate says, it was big enough that it made them want to try something new with their giving.

Like thousands of other Canadians across the country, they decided to establish a donor advised fund (or a DAF) — a charitable saving account, of sorts. In establishing their DAF, Bate and Marshall received a tax receipt for the full value of their initial donation, but also retained the right to recommend grants from the account over time to charities of their choosing.

They saw the DAF as a way to be more strategic with their giving, Marshall says — to give themselves time to make a thoughtful plan for where their gifts would go. They also knew it was a smart tax move. By making a larger one-time donation in the year Bate’s income was higher, they could reap greater tax savings than had they decided to dole the donations out directly to individual charities over many years.

Decision made, the couple had only one more hurdle to overcome before the December 31st tax deadline: deciding which foundation to establish their DAF with.

For the second half of the 21st century, Canada’s community foundations have been the obvious choice for donors looking to establish DAFs. But today, there are a number of new options, including a cohort of fast-growing foundations with close ties to the country’s banks and wealth management firms.

Tight on time, Bate and Marshall considered their local community foundation, but opted instead for BenefAction, a foundation that works closely with 400-odd financial advisors from across the country.

Over the last decade, the choice Bate and Marshall made has become increasingly common for affluent Canadians. In 2021, Canada’s five largest commercially-affiliated DAF foundations held $3.8 billion in charitable assets. Two decades ago, none of them existed.

It’s a trend, too, that shows no sign of slowing down.

In 2021, the last year for which complete information is available, seven of the 20 charities that received the most donations overall from Canadians were foundations that offer DAFs that are closely affiliated with banks and wealth management firms. By contrast, just one was a community foundation.

To understand the causes of the growth in commercially-affiliated DAFs and the trend’s impact on the charitable sector, Future of Good spoke with nearly two dozen people at the centre of this shift, including foundation executives, donors, fundraisers, and researchers.

We also compared the grants issued in 2020 by the country’s largest commercially-affiliated DAF foundations and their community foundations peers, to assess how the growth in commercially-affiliated DAF foundations may shape which charities receive support in the coming years.

For charity sector workers who are wary about the expanded role of financial institutions in the Canadian philanthropic landscape, the results of this analysis may be surprising.

Despite some concerns, sources who spoke with Future of Good were near-unanimous in their view that the increased presence of the country’s banks and wealth management firms in the charitable landscape should be seen as a positive development, based principally, on a belief that these institution’s affiliated DAF foundations are driving affluent Canadians to give more.

The rise of the commercially-affiliated DAF

Among financial institutions, Toronto Dominion Bank was Canada’s first mover in the DAF marketplace.

In October 2004, the bank launched the Private Giving Foundation, the country’s first bank-affiliated foundation to offer donor advised funds. In so doing, it followed in the footsteps of American investment giants, including Fidelity Investments, Charles Schwab, and Goldman Sachs, which had each established their own affiliated foundations in the years prior.

By design, Private Giving Foundation, like other commercially-affiliated DAF foundations, is formally independent from TD Bank. The ties between the two institutions, however, are close: TD put up the seed money for the foundation’s launch, several bank staff members sit on the foundation’s board, and the bank has a service agreement with the foundation to provide all of its administrative support. Perhaps most importantly, too, the bank’s legion of wealth managers and estate professionals also refer their clients to establish DAFs with PGF.

After the foundation’s launch, other Canadian financial institutions quickly followed.

In 2005, Royal Bank of Canada launched its own DAF program, working with Charitable Gift Funds Canada, a foundation based in Kingston, Ontario, which today also works with wealth managers at Bank of Montreal and National Bank.

In 2006, Mackenzie Investments followed TD’s archetype, launching Strategic Charitable Giving Foundation, which enabled the thousands of financial advisors who sell Mackenzie’s investment products to offer DAFs to their clients through the institution’s affiliated foundation.

And in 2008, BenefAction, the provider Bate and Marshall selected, was also created, offering independent financial advisors another platform for their clients.

For banks and independent wealth managers, the motivation for getting in the DAF business was simple, says Brad Offman, CEO of Spire Philanthropy: client retention.

Though financial institutions can earn money from DAF foundations, through charging investment management and service fees, Offman says this isn’t what drives the work. “In the grand scheme of things, the fees are inconsequential,” he says. Instead, it’s about providing a “strong, values-based product,” Offman says, and ensuring that clients aren’t “slipping through any cracks.”

“Financial institutions are very keen on retaining as much of their client’s wallet as possible, and the donor advised funds allow them to do that,” he says.

Why wealthy Canadians are choosing bank DAFs

Though most of Canada’s largest community foundations had a multi-decade head start on their largest commercially-affiliated DAF foundation peers, there are a host of reasons why foundations linked to banks and wealth management firms are now winning in the race to support their affluent clients to establish DAFs.

For one, experts say, the marketing might of the commercially-affiliated institutions is unmatched by community foundations.

Across the country, community foundation staff hustle to make prospective donors aware of their work, through webinars, newsletters and networking. They also work hard to build relationships with individual wealth managers, hoping advisors will refer their clients to the foundation.

By contrast, Offman says, banks and wealth management firms have built-in marketing channels with vast reach. “[Banks] can press a button and they can promote their proprietary DAF program to 1,200 or 1,500 advisors in a way that a community foundation would never be able to do,” he says.

Unlike financial advisors, too, community foundations have no visibility into a prospective donor’s financial situation before they receive a gift. By contrast, wealth managers are often able to see a client’s full financial picture, giving insight into the precise moment to raise the prospect of creating a DAF.

Experts say these conversations typically occur in two moments in a client’s life.

The first instance is when “money is motion,” says Jo-Anne Ryan, head of the TD-affiliated Private Giving Foundation, such as when a client is profiting from the sale of a business, receiving an inheritance, or getting funds from the conclusion of a divorce. In each of these moments, clients are often set to incur a larger tax bill, and for philanthropically-minded Canadians, a donor advised fund is one of the most tax-efficient ways to support charities.

These moments are also stressful and often rushed, a combination that can also give the upper hand to trusted advisors close at hand.

“When you have that happen, most people’s first thought is not to call up a community foundation to have a conversation with them, right? You’re talking to your financial advisor, because you’re like, ‘Oh, wow. How do I do this?’” says Celeste Bannon Waterman, a partner with KCI, a charitable sector consulting firm, who is working on a landscape research report about donor advised funds.

The second common instance where the possibility of creating a DAF is raised is during discussions about financial planning — when a client is setting up their will or taking stock of the performance of their investments at an annual meeting with their wealth manager.

Jeremy Clark, CEO of CH Financial Ltd, a Calgary-based wealth management firm, says he’ll suggest a DAF when he knows a client is charitably-minded (an easy short-hand is a tax return that shows existing charitable giving) and when it’s clear the client has the capacity to give.

These are good moments for a discussion about creating a DAF, Clark says, because a client’s financial plan will make it clear that they have more money than they will ever need in their lifetime and that their kids will be just fine, too.

Here, also, commercially-affiliated foundations may, too, have the upper-hand on their community foundation peers. “Our clients are very busy,” says Jo-Anne Ryan. “There is something to say for one-stop shopping.”

In addition to marketing might and their proximity to moments when financial planning occurs, Offman and others say there’s another big reason why commercially-affiliated DAFs are growing their assets more rapidly than community foundations: financial incentives.

In general, wealth managers earn commissions based on the total value of assets they steward. In most cases, supporting a client to establish a DAF at a community foundation means less money on their books — because, most commonly, their client’s donation will be held within the foundation’s endowment, which is managed by the foundation’s chosen investment managers. For a client’s wealth managers, this poses a “fundamental business paradox,” says Offman.

The country’s largest commercially-affiliated foundations, by contrast, eliminate this challenge.

When they established their DAF with BenefAction, Bate and Marshall were able to recommend that their existing wealth managers at RBC continue to manage the assets they donated to the foundation. Rather than putting charitable assets into an endowment, BenefAction’s model instead, is to generally support a client’s chosen wealth managers to continue to act as the investment manager for their client’s DAF assets — to be the ones to decide which stocks, bonds, and other funds the assets will be invested into until they are granted out.

For Bate and Marshall’s advisors at RBC, this was good, because it meant they wouldn’t lose the assets under management. But it was also a selling feature of BenefAction for the Toronto couple, because they trust their financial advisors and were glad to see them be the ones to continue to manage their charitable fund.

In recent years, some community foundations have begun allowing wealth managers to continue to manage their client’s DAF investments, but this is not the standard approach. Moreover, some community foundations only allow this when a DAF is large. At Toronto Foundation, the community foundation Bate and Marshall considered, the couple would have needed to establish a DAF with at least $5 million in assets to be permitted to recommend their wealth managers.

Fundamentally, Offman says, wealth managers aren’t suggesting their clients set up DAFs with commercially-affiliated providers for the commissions. They’re doing it, he says, because DAFs are a good product that meet their clients needs.

Still, he says, it’s true the added financial incentive has helped commercially-affiliated providers grow their DAF assets more rapidly than their community foundation peers.

“What the bank programs did and what the financial institution programs did was they created a business model that was inherently better suited for the advisors,” he says.

What does the rise in bank DAFs mean for charities?

With commercially-affiliated DAFs on the rise in the United States and in Canada, some fundraisers, charitable sector advocates, and community foundation staff have expressed a variety concerns — around transparency, grant distribution, and whether commercially-affiliated DAF foundations are growing the overall amount of money in the charitable sector, or just shifting it around.

One fundraiser who spoke with Future of Good and asked to remain anonymous, said his principal concern is that DAF foundations make it more challenging for him to build relationships with affluent donors and solicit follow-up gifts.

When donors give directly to his charity, a mid-size, Ontario-based social service organization, they generally have to provide their contact information — their name, email, and phone number. By contrast, when a DAF grant is made, recipient charities are rarely provided with any information about the donor who has recommended the gift, unless the DAF holder is a pre-existing donor to the charity. This makes it challenging, the fundraiser says, to build a relationship with the donor and potentially secure follow-on gifts. “When we talk about donor advised funds, it’s like a cloak,” he says.

Several executives at DAF foundations confirmed they don’t often provide donor contact information to charity grant recipients. Two executives said this is so, in part, because they view it as their responsibility to “protect” DAF holders from solicitation from charities. They said many DAF holders are, in fact, drawn to DAFs because they provide more anonymity than had the donor given to a charity directly.

Yet, while other fundraisers who spoke with Future of Good acknowledged the intermediary role of the DAF foundation changes the access fundraisers have to DAF holders, not all viewed it as a significant concern.

Conor Tapp, director of fund development for CUPS, a Calgary-based social service agency, says, by contrast, that he’s been able to build solid relationships with staff at DAF foundations, and that these professionals have actually provided him with insights about prospective donor’s communication preferences — whether they prefer graphics, text, or data, for instance — which have helped him to improve his donor appeals.

For fundraisers looking to find new DAF donors, Tapp says cold-calling Jo-Anne Ryan or Jeremy Clark isn’t the way to do it. Instead, he says, he’s found success in connecting with wealth managers and donor advisors in the places where they gather, like the annual Canadian Association of Gift Planners (CAGP) conference.

“If I have a solid pitch, I’m in the right places, and I’m saying the right things, they’re going to invite me to say more,” says Tapp, whose organization operates on the traditional territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuut’ina First Nation, and Stoney Nakoda Nations, and is home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3.

Last year, he says, CUPS secured more than a quarter of a million dollars in gifts from DAFs from commercially-affiliated and community foundations.

“These are professionals who love their work and who do well when their clients do well,” he says, of financial and donor advisors. “So if we help them, they’re going to reciprocate with us.”

Where do the grants go? Both types of DAF foundations supporting larger organizations

Beyond frustration about DAF foundations blocking access to donors, one community foundation executive, who asked to remain anonymous, told Future of Good in November that she was concerned that growth in commercially-affiliated DAFs could mean less money for smaller, local charities.

The executive noted the extensive work of many community foundations to educate their fundholders about challenges in their cities, including through their annual Vital Signs research reports. Commercially-affiliated DAF foundations, she said, don’t do this kind of education and offer less in-depth donor advisory support. She believed a review of their grants would show more support from commercially-affiliated DAFs for large organizations — hospitals, universities, and big name charities.

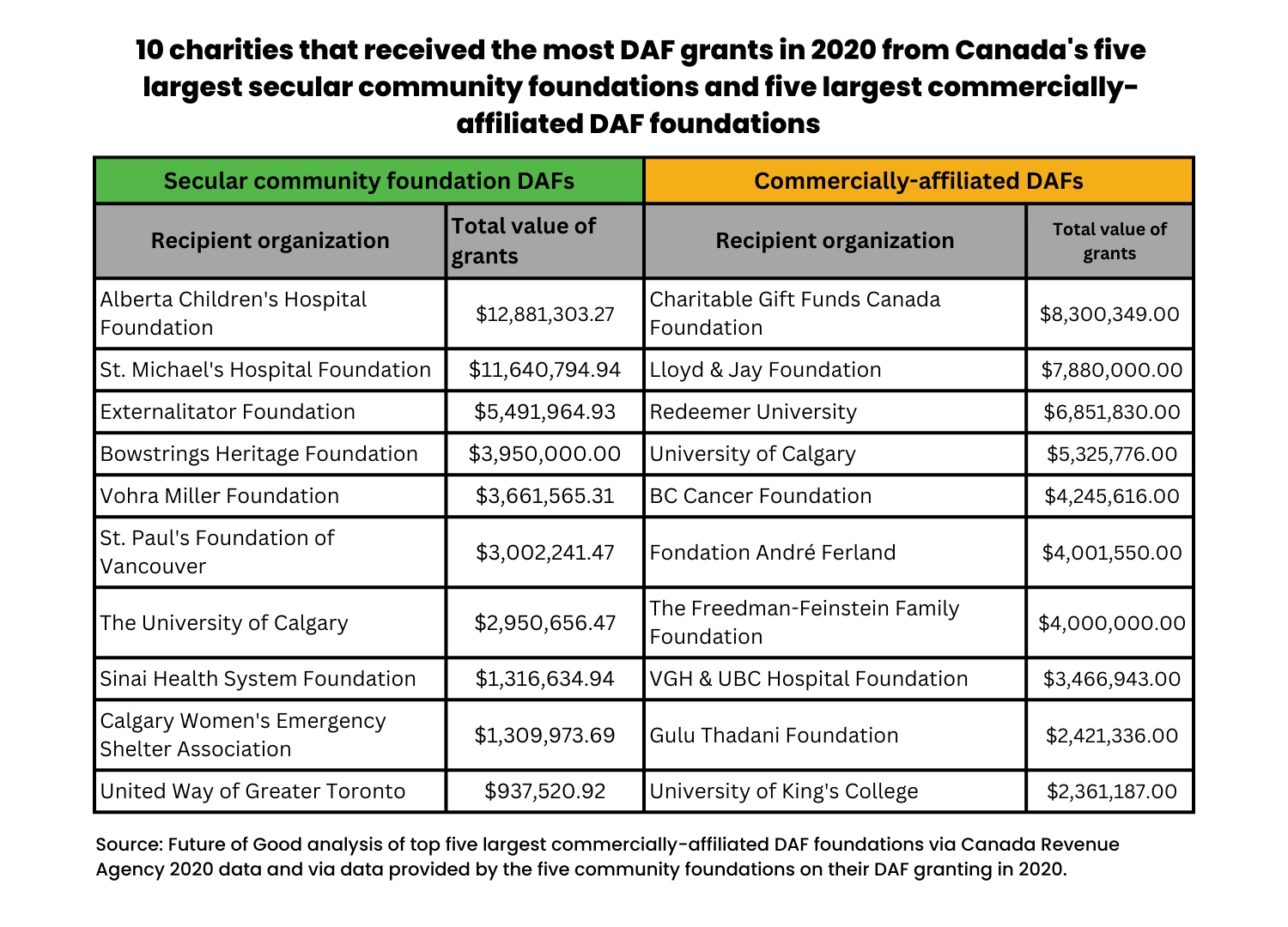

To test this hypothesis, and understand how the growth in commercially-affiliated DAFs may shift granting patterns, Future of Good compared the 2020 DAF grants from the country’s five largest secular community foundations — Winnipeg, Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton and Toronto — with those of five of the country’s largest commercially-affiliated DAF foundations — Charitable Gift Funds Canada, Aqueduct, Private Giving Foundation, Strategic Charitable Giving Foundation and BenefAction.

In our analysis, we excluded two organizations in the top five for each category — the Jewish Community Foundation of Montreal, because of its religious focus, and CHIMP: Charitable Impact Foundation, a Vancouver-based DAF provider, because it provides DAFs to everyday donors in addition to donors recruited through financial advisors.

We found that, in 2020, a far larger share of the five largest secular community foundation’s DAF grants indeed flowed to charities in each institution’s home cities.

In 2020, 85 per cent of the DAF grants from the country’s five largest secular community foundations went to charities within the cities where those foundations operate. By contrast, and perhaps, not surprisingly, charities in those five cities secured just 41 per cent of all grants from the five commercially-affiliated DAF foundations in 2020. (The five commercially-affiliated DAF foundations serve Canadians across the country, and their grants reflect this wider focus.)

By contrast, however, we did not, as the community foundation executive suggested, find that a larger share of the 2020 DAF grants from the country’s largest secular community foundations supported smaller organizations, when compared to their commercially-affiliated DAF foundation peers.

We found instead that while the DAF grants of both types of institutions disproportionately supported larger charities in 2020, it was actually the commercially-affiliated DAF foundations that flowed a greater share of funds to smaller organizations.

In 2020, 90 per cent of Canada’s 85,000-odd charities reported ten or fewer staff, according to Canada Revenue Agency data. Yet these organizations netted just 42 per cent of the 2020 grants from the five commercially-affiliated DAF foundations ($106 million) and just 33 per cent of the 2020 DAF grants from Canada’s five largest secular community foundations ($41 million).

Analyzed by charity revenue, the results are similar: While both types of institutions sent a disproportionate share of grant funds to larger charities, community foundations gave more to the biggest charities, relative to their commercially-affiliated peers.

In 2020, just 1 per cent of Canada’s charities had revenue of over $50 million, according to CRA data. In that year, however, 27 per cent of the grants from the five commercially-affiliated DAF foundations went to these organizations ($68 million) and 37 per cent of the 2020 DAF grants from the country’s five largest secular community foundations went to these charities, too ($45 million).

Reflecting on this data, community foundation executives explained the finding in three ways: brand recognition, charity capacity and the true nature of advisory services at both types of institutions.

Noel Xavier, director of donor services at Edmonton Community Foundation, says DAF holders are much like other Canadians in their knowledge of the charitable landscape and in their willingness to give more money to charities they know and trust.

“Ask any Edmontonian to name five charities in Edmonton, and probably most of them are going to name the same five ones,” he says. “It’s the five biggest ones, and it’s the ones that have the most name recognition on the street.”

At both types of DAF foundations, big name institutions — universities, hospital foundations, and charities with high brand recognition, like United Way of Greater Toronto, were among the top ten recipients of the most funds.

Hospital foundations, universities, private foundations, and well-known charities were among the top recipients of 2020 DAF grants from the country’s five largest secular community foundations and commercially-affiliated DAF foundations. (Graphic: Gabe Oatley)

Hospital foundations, universities, private foundations, and well-known charities were among the top recipients of 2020 DAF grants from the country’s five largest secular community foundations and commercially-affiliated DAF foundations. (Graphic: Gabe Oatley)

Eva Friesen, CEO of the Calgary Foundation says that while the significant share of DAF funds flowing to big charities might ruffle feathers, it is reflective of the capacity of sector organizations to provide services for communities.

“It would appear like the lion’s share always goes to the big guys, and that might have a negative connotation,” Friesen says. “[But] in fact, it is those large institutions like universities and hospitals that deliver so much more service than a new, small, grassroots organization can.”

As for why granting patterns, aside from geography, are similar between commercially-affiliated DAF foundations and community foundations, foundation staff say, in reality, the advisory support provided by the two types of institutions isn’t so different after all — staff from both types of institutions will provide some granting advice to donors if they want it, or staff will leave donors alone if they’d prefer that, too.

“The fact of the matter is that the way we deliver DAFs and the way the private entities deliver DAFs is not fundamentally different,” says Julia Howell, Toronto Foundation’s chief program officer. “We’re all just responding to the donor advisor’s recommendations on where to grant and we’re facilitating those grants.”

Are commercially-affiliated providers growing the pie, or crowding out others and “hoarding” charitable wealth?

Beyond concerns about blocking relationship-building with donors, or that small charities might be shortchanged by the growth in commercially-affiliated DAFs, there’s a third concern that has worried some Canadian sector advocates: that rather than bringing new donations into the sector, commercially-affiliated DAF foundations may just be taking it away from community foundations or from working charities themselves — slowing the productive use of these donations in the sector.

Currently, DAF foundations, both community foundations or commercially-affiliated DAF foundations, are only subject to a foundation-wide disbursement quota of 5 per cent.

This means that though donors receive the full value of their tax advantage in the year they make a donation to establish their DAF, individual DAFs are not required to grant each year, so long as their DAF foundation is granting enough overall to meet the minimum requirement.

This has led some to accuse DAF foundations of steering donors away from granting to working charities, who would use the funds immediately, in favor of promoting the “hoarding” of charitable funds that are subsidized by Canadian taxpayers.

But foundation executives, both at the country’s largest community and commercially-affiliated DAF foundations, reject this argument.

Staff from ten of the country’s DAF foundations who spoke with Future of Good said they work hard to encourage DAF holders to get money out to the community. Five of these foundations also noted that their institutions have policies that require DAFs to grant an annual minimum each year — a policy some advocates have called for the CRA to mandate sector-wide.

In 2023, for instance, fundholders with BenefAction, Strategic Charitable Giving Foundation and the Winnipeg Foundation must each recommend grants totalling at least 5 per cent of their DAFs total assets. At the Aqueduct Foundation, it’s 4 per cent, and at Vancouver Foundation, fund holders must recommend at least one grant.

Karen Hudson, BenefAction’s vice president of growth initiatives, says this policy isn’t new or a response to disbursement quota-related advocacy in recent years — rather, it’s been in place since the foundation was established, rooted in a belief in the importance of keeping money moving. At Aqueduct, too, the policy has been operational since the foundation was launched in 2006, according to the foundation’s lead staffer, Malcolm Burrows.

Further, beyond the speed at which money is flowing, commercially-affiliated foundation staff who spoke with Future of Good were also adamant that their institutions are growing the overall amount of money available in their charitable sector — not simply taking money away from community foundation DAFs or gobbling up money that would have gone directly to charities in the form of direct donations.

Researchers and community foundation staff we spoke with tended to agree, too.

Sector consultant Celeste Bannon Waterman says it’s likely some donors who have established a DAF with a commercially-affiliated foundation would have set one with a community foundation had the commercial option not been available. But, she says, it’s also the case that the vast reach of the commercially-affiliated providers is growing the pie. “It’s not all new [money],” she says, “but more of it is net new.”

Of the three DAF holders who spoke with Future of Good, all said they believed creating a DAF has prompted them to give more than they would have otherwise. Further, only one donor said she would have established a DAF with a community foundation had a commercially-affiliated DAF not been an option.

A 67-year-old retired Torontonian said she learned about the potential to create a DAF when she and her Scotiabank advisor were working on her will. The donor, who asked to remain anonymous, says that had she not established the charitable fund through the bank’s affiliated foundation, the Aqueduct Foundation, she likely wouldn’t have known about the possibility of creating a DAF at all.

She adds that through her DAF, she’s ended up giving more than she believes she would have otherwise.

Upon establishing her DAF, the donor spoke with foundation staff about the particular type of medical research she wanted to fund. Foundation staff then helped her to arrange calls with relevant medical researchers seeking funding for new work. Were she to have given directly to charities themselves, the donor says, it’s unlikely she would have had this access, and unlikely she would have felt compelled to give as much as she has, over time, to support their work.

Bate and Marshall, too, say their DAF has prompted them to donate more into their fund with funds from the sale of Bate’s business than they would have otherwise.

Marshall says that in the harried moments before year’s end, it would have felt more “risky” to make a few, much larger donations to a couple of charities directly. By contrast, the DAF gave them time to sort out their plan.

Marshall says he also believes the DAF may prompt them to give more money to less well-known charities, because they now have more time to research the charitable landscape.

Reflecting on these trends, Bannon Waterman says most donors don’t have a fixed amount for their charitable giving — that if they didn’t give through a commercially-affiliated DAF foundation they would have certainly donated the same amount to establish a community foundation DAF or given it directly to several charities.

It’s more common, instead, she says, that donors are making trade-offs between consumption spending and charitable giving. From a donor’s perspective the question is: “‘Do I go buy a Tesla? Or do I give some money into my DAF?’” she says.

Bate agrees, noting that once an initial DAF donation is made, a DAF holder no longer has the option of using that money to buy a new car, or some other nice-to-have item.

Jeremy Clark, the Calgary-based financial advisor, draws a conclusion that is similarly rosy for charitable giving. In establishing a commercially-linked DAF, it’s his client’s children — not charities or community foundations — who he sees losing out on some money.

“If you were to say, charities versus family as a percentage of someone’s estate, I think where DAFs are really useful is in shifting some of that [wealth] from a family to charities,” he says.

Growth horizon: Just ‘scratching the surface’ of the DAF market

This year, Kate Bate and Patrick Marshall will join thousands of Canadians in selecting a group of charities to receive grants from their DAF.

It’s an exciting prospect, Bate says, allowing them to expand upon the work they began with Together Project, by providing support to a variety of organizations for many years to come.

Over the next decade, if trends continue, more and more Canadians will make the same decision the Toronto couple did — donating to establish a DAF with a commercially-affiliated foundation and then sending it out the door to charities across the country.

Jennifer Button, Charitable Gift Funds Canada’s lead staffer is seeing this trend in real time. Last year, the foundation’s DAF grants nearly doubled — from $80 million in 2020 to over $150 million in 2022.

Private Giving Foundation’s Jo-Anne Ryan, too, sees continued acceleration on the horizon.

“I think we’re just scratching the surface,” she says.

—

Methodology: For this story, we compared the 2020 DAF grants from Canada’s five largest secular community foundations with the grants from five of the country’s largest commercially-affiliated DAF foundations as of 2021. To do this analysis we asked the five largest secular community foundations to provide us with a list of their DAF grants from 2020, and we asked CRA to provide us with the same list for the five commercially-affiliated DAF foundations. From CRA, we also retrieved the list of all registered Canadian charities in 2020, including the charity’s address, number of full-time staff, revenue, social impact category and sub-category. We then merged the foundation DAF grant datasets with the charity dataset, and analyzed by: recipient charity organization type, geography, size, and social impact area. For additional analysis of this data, including additional graphs and tables, click here.