As Boomers retire, non-profits are saving local businesses for non-profit purposes. Is this something your organization could do?

Why It Matters

The Government of Canada’s Social Innovation and Social Finance Strategy acknowledges a need for more social innovation focused on Canada’s more persistent and complex challenges. It also seeks to grow Canada’s social finance sector to catalyze community-led solutions to such challenges. Considering the context of significant entrepreneurial transfer, social acquisitions emerge as both a solution to the small business continuity problem and a way to leverage the growing social economy.

It’s a growing trend, and it’s rewriting the story of how social impact transforms traditional business practices.

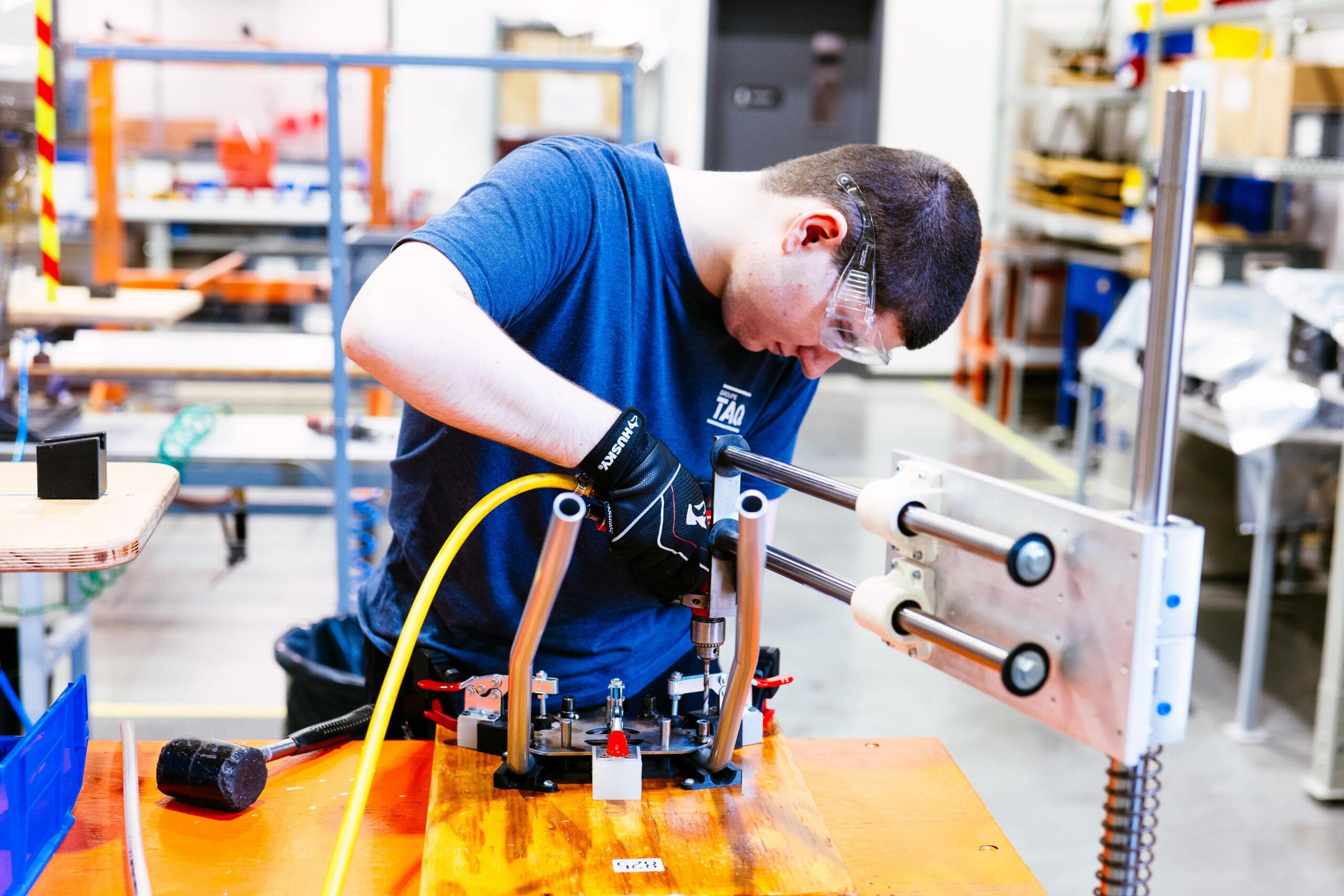

“Our non-profit mission is to provide jobs for people with disabilities,” said Groupe TAQ’s CEO Gabriel Tremblay.

“However, our business activities vary. We’ve done mail preparation, snowshoe assembly, food preparation, and it will keep changing to seize growth opportunities.” Four months into Tremblay’s arrival, TAQ bought a competitor in the mail preparation industry. This was after a similar acquisition TAQ made in 2021, where they purchased a snowshoe assembly client.

The non-profit plans to continue this type of growth with a third acquisition within the next two years.

Meanwhile, at Malartic Golf Club, its members’ acquisition was aimed at another type of impact: preventing the loss of a social landmark.

“Our nine holes golf club is the focal point of our community. We meet, we golf, and we celebrate life’s big and small moments,” said Alexy Vezeau, a club member and the controller at Agnico-Eagle Mining.

“And it is where I had my summer job,” he added with a smile.

Tremblay and Vezeau had different goals. However, the solution was the same: social acquisitions.

It’s what happens when a conventional enterprise is bought and restructured into a social economy or purpose organization.

As Baby Boomers retire, there is momentum for social acquisitions, said Kristi Fairholm Mader, Director of Innovation and Initiatives at Scale Collaborative in B.C.

Why are social acquisitions popular now?

“A huge intergenerational transfer is building up,” said Mader, who is also the managing director of place-based Thrive Impact Fund.

Luc Malo, collective takeover coordinator at Quebec Centre for Business Transfer, said since 2021, the province of Quebec has processed more business transfers than business creations.

Those transfers are critical for Canadian communities.

In B.C., for instance, there are 400,000 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They are responsible for half the jobs and one-third of the provincial GDP. In rural B.C., seven out of ten SMEs are owned by boomers, many of whom will retire in the next five years.

“It is an opportunity for non-profits, community organizations and co-operatives to develop new revenue streams and leapfrog without the risk associated with starting a new business,” said Mader.

“It’s also an opportunity to grow the social economy sector by adding new organizations created from the transformation of conventional businesses,” she added.

Moreover, group entrepreneurship is trendy, said Jérôme Gagné, project management advisor for Le Conseil Québécois de la Cooperation et de la Mutualité.

More than half of for-profit businesses are now owned by groups, whether they plan to launch a business or buy one, according to the 2024 Entrepreneurial Index from La Sphère at HEC Montréal.

One-to-one transactions will be less frequent unless the entrepreneur is wealthy or has access to a large pool of capital, said Gagné.

“Because of the price, the complexity of business models and the mental load, it becomes natural to undertake in a group.”

This trend benefits non-profits, cooperatives, and community organizations naturally working in groups.

A matter of positioning

In April 2022, the Alberta Community Cooperative Association hired business acquisition platform Village Wellth to accelerate social acquisitions in Western Canada.

“The intent was to launch investment co-ops to buy businesses in rural communities,” said Elizabeth MacRae, president and head of partnerships at Village Wellth.

However, the project fell apart because of a lack of champions in communities, said MacRae, noting that they could not mobilize enough people to form co-ops to facilitate acquisitions.

“There is an awareness challenge; most non-profits don’t know they can acquire companies,” she added.

Lori Camire, executive director of Community Futures Alberni-Clayoquot, said a few Community Futures Canada offices are considering venturing into social acquisitions. But only her office did.

Community Futures Canada is a network of 267 non-profit organizations supporting economic and community development in rural and remote communities.

Camire’s office bought Coombs Country Candy in November 2020 for $270,000. The 45-year-old store was a community feature with the potential to grow their online sales, she said.

The Community Futures Alberni-Clayoquot office owns Venture Connect, a subsidiary that provides services for selling and purchasing businesses in remote and rural Canadian areas.

“This expertise is unique in the Community Futures network. It made it easy for our office to identify the Coombs Country Candy opportunity and feel comfortable acquiring it,” said Camire.

To acquire or not to acquire?

Camire said any social acquisition should start with this question: ‘Does our organization have the energy, the talent, and the risk mindset to do it?’

Groupe TAQ’s CEO is a born entrepreneur, and that has made a difference for TAQ. “I run it like a for-profit, except the profits are reinvested to fulfill the mission,” said Tremblay.

He frequently invites local entrepreneurs to tour his facilities.

“Most business owners do not announce publicly their intention to sell. When they do, they rarely consider non-profits or community organizations as potential buyers. I want them to think of us,” he said.

Business visitors touring TAQ see hundreds of employees assembling cookie packaging, producing components for Quebec and Ontario Hydro, manufacturing snow shoes and even cooking chocolate fondue, Tremblay added.

An acquisition binge isn’t right for all non-profits. Still, Mader said that in order to make it happen, someone with an entrepreneurial mindset needs to be involved in the decision-making process to see the opportunity for a social acquisition.

That person could work in the organization or be a consultant, partner, or client.

Mader added that a good social acquisition makes sense operationally, revenue-wise, and mission-wise. It should also advance the values, mission, or organizational objectives, including additional revenues.

Non-profits do not need to run the new business if the expertise does not leave with the owner, said Camire

Since being bought, Coombs Candy Store has been managed by Leanne Hewitt, a 19-year employee who has done every job from entry-level to purchasing. The rest of the staff also stayed after the transaction.

“You do not need to understand the business you’re acquiring inside out, but you must understand the margin. How does it make money?” said Carla Leon, CEO of the social franchise Just Like Home Care.

One of the big benefits of social acquisitions is that they can further a non-profit’s impact.

“A food-producing organization promoting food security could acquire the local coffee shop next door to give their brand and products a higher profile in the community,” said Sean Geobey, associate professor at the University of Waterloo who led the Legacy Business Lab on the social acquisition movement.

They can prevent the closure or secure the future of an essential community business, such as the grocery store, shoe store, or golf club, or simply add a revenue stream.

“But make sure the non-profit can run this social acquisition while keeping committed to its mandate,” warned Geobey.

He cited the U.S. YMCA’s struggles in 1990, where many had difficulty maintaining their charity status because their gym activities were dominant.

“In such a situation, either the Finance Ministry or your donors will question your business move. Social acquisitions should be additive, not dilutive,” said Geobey.

There is nothing wrong about a non-profit being opportunistic, added Leon.

“But if you buy a business having nothing to do with your mission, make sure it is profitable and that it is not a distraction or a nuisance to your mission,” she added.

The good news is there are ways to test the water.

“I’ve seen non-profits partnering with local businesses, renting the space for a day to host events or operating for a day every week to understand the business,” said Leon.

Never without an appraisal

Thrive Impact Fund invests in and supports B.C. non-profits, cooperatives, and for-profit social enterprises. Therefore, “organizations often contact us to finance an acquisition they agreed upon without formal appraisal,” said Mader.

In one case, Thrive’s intervention reduced the acquisition price by more than half, from $250,000 to $100,000.

Mader said SME owners often think their business is worth more because of all their hard work, and this becomes an emotional issue.

However, the numbers may not add up because the owner did not pay themselves or their salary was lower.

“After the acquisition, you will hire a manager. It changes the bottom line,” added Leon.

Maintenance and updating issues also influence the acquisition price. For example, the Just Like Family Home Care website was outdated, meaning “we needed to invest $100,000 right after the acquisition,” she said.

The tax structure should also be considered when transforming a for-profit into a non-profit, a cooperative or a community organization. Sole owners get different tax exemptions than social economy organizations.

Malo said any acquisition process should start with a seller agreement that gives access to all the data required for the appraisal.

“It is a condition for getting a subsidy to finance the appraisal,” he added.

Quebec’s Ministry of Economy, Innovation, and Energy subsidizes up to 70 per cent of the seller evaluation and 70 per cent of the buyer appraisal and due diligence process.

The seller agreement should also specify that the seller will sell if the price is right.

“We had two stories where the entrepreneur pulled out the rug at the last minute,” said Mader.

In both cases, the non-profit handled the whole process, and the board approved the deal, but then the entrepreneur no longer wanted to sell.

Lastly, business performance varies over time, such as in the stock market.

“Is the sector influenced by financial, regulatory or environmental trends affecting its future performance? Are there trends boosting its perspective?” said Mader.

How about getting financed?

The Malartic Golf Club acquisition was a $912,000 project.

Community bonds financed the down payment. “We raised $75,000 from 80 citizens who paid $500 or $1,000 each for a five-year term. Instead of paying interest, we offered a rebate on the membership or free games,” said Vezeau, who chairs the members’ Association.

This $75,000 will be doubled through Fonds l’ampli, a fund from le RISQ, capitalized by Lucie & André Chagnon Foundation.

The association also received a $220,000 loan from the Investissement Quebec collective takeover program and a $198,500 patient capital loan from La Fiducie du Chantier de l’Économie Sociale. The City of Malartic cautioned both loans.

“We haven’t reached out to the corporate universe yet, but we will keep this option for the future,” said Vezeau.

The transaction took eight months.

“A private entrepreneur can offer personal or business guarantees. Our association started from scratch. We knocked on many doors to come up with a financial arrangement. Each lender had different ask and proceedings,” said Vezeau.

Leon syndicated three charities and nine private investors to acquire Just Like Family Home Care. She tells the story in her book Win Win Capitalism: Transforming Business through Social Acquisitions.

“I knew the company because, as a social innovation consultant for United Church of Canada, I helped Broad View United Church buy and finance the Victoria and the Nanaimo franchise in 2019,” said Leon.

She suggested to the United Church of Canada that they buy the whole business when it was up for sale, but they declined. In the blink of an eye, Leon decided to make the acquisition herself.

“I was booking my meetings with charities’ boards and investment committees while due diligence was being done,” she recalled. It was essential to get an anchor investor fast.

She signed the United Church of Christ Church Building & Loan Fund for 37 per cent of the ownership. Broad View United Church and a third charity whose involvement is not public completed 50 per cent of the ownership.

“Those are the only three charities who agreed to finance this acquisition; everybody else said no,” said Leon. The rest of the money came from nine private investors.

“This acquisition was so successful and continues because no one bought it alone.

Partnering with other charities, community organizations, or non-profits makes sense for those transactions, said Leon.

Updating government programs

While charitable or private funding is a way to gather financing, there is also government financing for social acquisitions.

“Investissement Québec program managers are very collaborative,” said Vezeau, but added these programs are underused.

“As social acquisitions gain momentum, they will benefit from being more tested by the people who administer them,” he said.

The situation is similar in the rest of Canada. According to Geobey, a wide range of economic development programs offered by the federal and provincial governments are implicitly tailored to for-profit corporations.

Co–operatives and non-profits have long been unable to access them, even though, in theory, the policies and legislation should make them eligible.

“In practice, they are not accessible because the people who administer and run those programs aren’t aware of these options. It is about bringing up to date a lot of policy structure and government programs to include various structures,” he said.

For instance, the Business Development Bank of Canada finances acquisitions by for-profit social enterprises and mentions employee buyouts in its succession planning section, but it does not mention social acquisitions.

So what happens if non-profits solicit traditional bank financing for social acquisitions?

The idea of a non-profit buying a for-profit is relatively new, said Camire. “I hope that the financial institution will say, ‘Interesting idea. Can you afford to do it?’

“A non-profit needs to be profitable; the only distinction with a for-profit is where you spend your profit. You can’t get rich. You have to put your money back into your business,” she added.

Challenges and limits

When an entrepreneur wants to sell, she usually turns to her advisors: the accountant, the lawyer, and the wealth manager. Their lack of knowledge and understanding of social acquisition are barriers to address.

“For-profit corporations still conduct most Canadian economic activity. Thus, most lawyers and accountants are trained to work with corporations,” said Geobey.

This is a chicken and egg phenomenon, he added, noting you can’t have more social acquisition without more trained professionals, and you can’t have more trained professionals unless there is a market for social acquisitions.

The easiest path forward, then, is for all professions to have associations that require consistent, updated training to maintain their credentials.

“I’m not saying these associations should force every Canadian lawyer and accountant to learn about co-op law, but they could offer ongoing professional training on it,” said Geobey.

Scale Collaborative recently published a report summarizing the essentials of social acquisitions and webinars about creating community wealth.

In Quebec, collective takeover experts created a website centralizing all the information, including a training section. “We encourage entrepreneurs to watch these webinars with their advisors,” said Gagné.

In 2025, Quebec’s municipal and regional economic development experts will be trained in social acquisitions, said Malo.

Advisors can facilitate social acquisitions, but non-profit and community organization managers or cooperative members initiate them.

“We are working on a class about social acquisition to stop relaying the default position that it is not possible,” said Emeline Le Guen, Development agent at Chantier de l’Économie Sociale.

The Coombs Candy acquisition is proof it can be successful and even unexpected.

“The community respects us more because we care. They discovered that we bought a business and transformed it into a social enterprise. The term ‘social enterprise’ was new, and people asked what it meant. They liked it,” said Camire.