Axe the tax … and then what?

Why It Matters

All candidates for Canada's PM job have vowed to end the carbon tax but the details are fuzzy. What is each candidate referring to: the consumer carbon pricing on fossil fuels or the industry carbon pricing on pollution? Keeping the end goal of stopping climate change, what is the best strategy for environmental advocates: keep lobbying for the tax or move on?

It’s been Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission’s message since 2018: carbon pricing is the most cost-effective way to reduce greenhouse gas pollution.

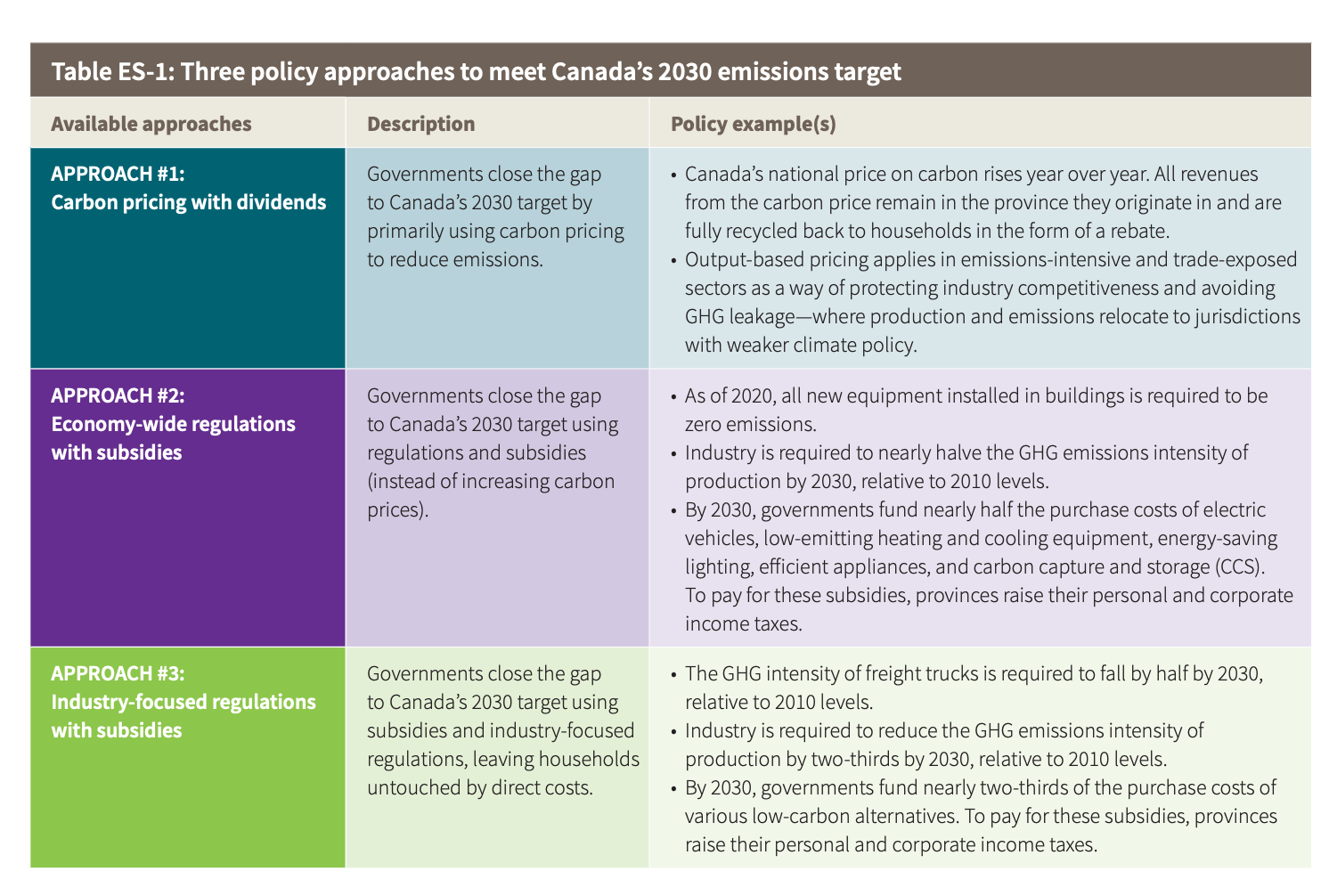

A stringent, rising carbon price will help Canada meet its 2030 climate target (a reduction of its emissions of 40 to 45 per cent) at the lowest possible cost to the economy, businesses, and households, according to the independent economic group.

In Canada, that takes the form of carbon fee for everyday consumers – an extra cost on products that produce carbon when used, like natural gas, gasoline and oil.

And yet, all the party and candidate leaders for the federal government have said if they are elected, they will get rid of the carbon tax, with Conservative Leader Pierre Pollivere turning the issue into an “Axe the Tax” slogan.

If we eliminate the consumer carbon fee … how do we lower emissions?

How carbon pricing works

Carbon pricing is a fee imposed on the production and consumption of fossil fuels to create an incentive to pollute less by migrating to low-carbon options.

The fee is imposed for every tonne of carbon emitted.

The government of Canada implemented carbon pricing in 2019, the fee was $20 per tonne. It has increased by $15 annually and will reach $170 in 2030.

Consumers pay this carbon fee when heating their homes or filling their cars with fossil fuels, and businesses pay for carbon emissions from production and transportation.

Since 2023, 73 carbon-pricing systems have been used worldwide, covering 23 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Carbon pricing’s broad reach is what makes it effective. It provides incentives to reduce emissions across the economy, regardless of their source. It applies upstream to suppliers of coal, natural gas facilities, and oil refineries and downstream to energy-using industries, households, and vehicles.

And unlike subsidies, putting a price on carbon does not require raising other taxes to finance it.

However, consumer carbon pricing will likely be eliminated after the next federal election.

The fate of carbon pricing for industrial emitters is unclear from the Conservative agenda, but the Liberal candidates’ declarations suggest they would maintain it.

Climate policies work in layers, but their impact varies. According to the Climate Institute of Canada, industrial carbon pricing will reduce emissions three times faster than consumer carbon pricing.

Yet, it was a Conservative government that brought in the first North American carbon pricing program in 2007.

The Specified Gaz Emitters Regulation was implemented in Alberta as a market-based solution to ensure that higher polluters paid for the damages their pollution contributed.

Carbon pricing was initially called a “price on pollution.”

“It was the original storytelling,” said Julie Segal, Senior Program Manager, Climate Finance, Environmental Defence, an environmental advocacy organization.

“Over the past years, the Conservative Federal Party shifted that label to a carbon tax,” she added.

Why carbon pricing is a textbook case of lousy storytelling

Nobody likes a tax. But is carbon pricing a tax?

Monica Curtis, of Alberta-based clean energy think tank Pembina Institute, , said a tax is a way for a government to collect revenue to pay for its services to the population.

“Carbon pricing is being managed through the government. So, in that view, it is a tax. However, unlike income tax, carbon pricing is tied to a particular choice that you are making. You pay for choosing to run your vehicle or heat your home on fossil fuel. Income tax is not tied to a choice,” added Curtis.

Therefore, carbon pricing, especially consumer carbon pricing, has become a textbook case of bad storytelling.

“Putting a price on carbon rewards consumers who choose a low-carbon lifestyle,” said Pierre-Oliver Pineau, Chair, Energy Sector Management at HEC Montreal.

“Moreover, carbon price has not been high enough to affect consumers with a high-carbon lifestyle. Fuel prices at the pump fluctuate so much because of producers’ decisions and the economic and political situations that the carbon pricing effect is lost in those fluctuations,” added Pineau.

Most Canadians will actually become poorer when consumer carbon pricing is eliminated because they won’t receive the quarterly checks associated with this policy, the Canada Carbon Rebate.

In 2024, those checks varied between 95$ (New Brunswick) to 250$ (Alberta) per person. The amount depends on the size of your family and the province where you reside. There is a 20 per cent supplement if you live in a small or rural community.

“Canadian politicians decided they won’t waste time and energy in an irrational debate over the consumer carbon price. They will go for alternative climate policies with a better chance to be effective and politically acceptable,” said Pineau.

Visibility is at the core of public policies.

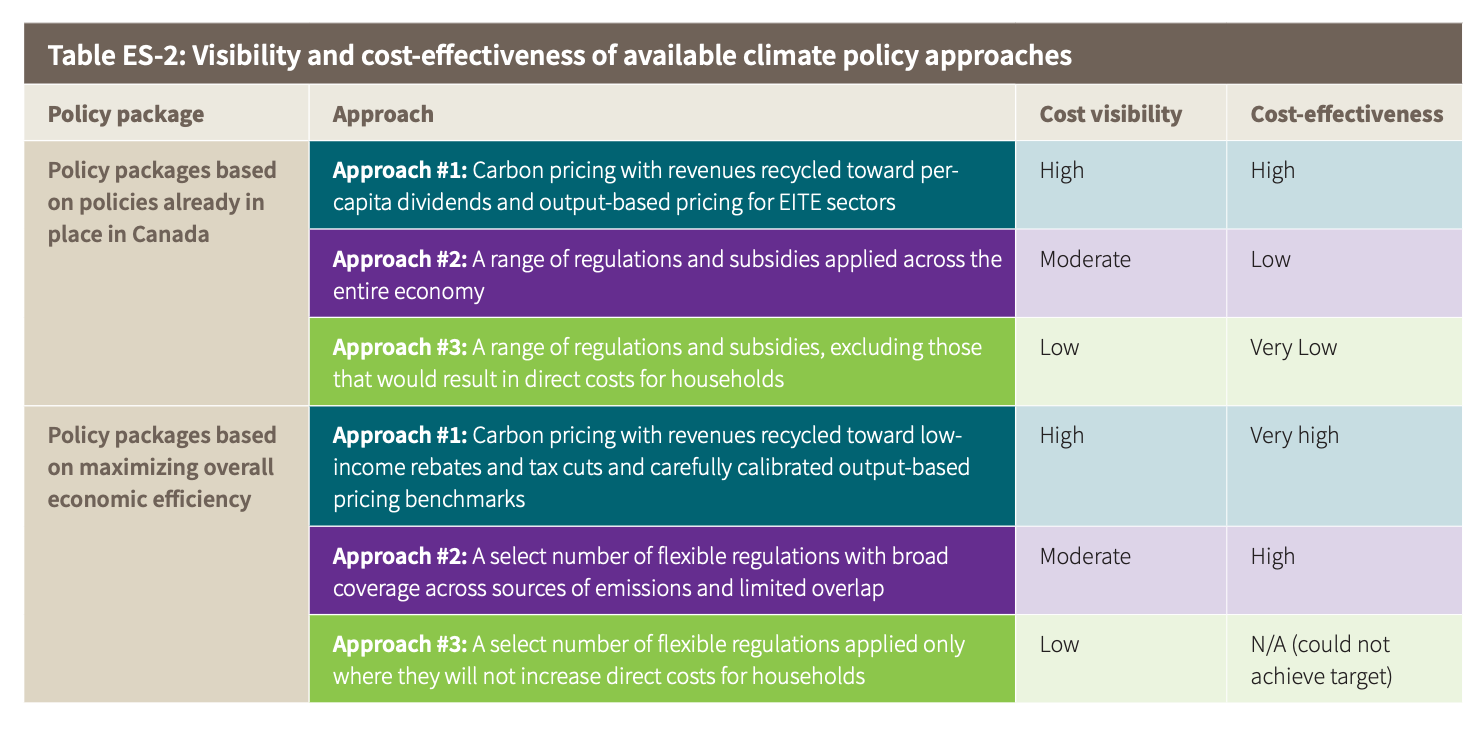

Politicians can access three climate policy tools: carbon pricing, regulations, and subsidies, each with different visibility levels.

Carbon pricing is highly visible. Since emissions are explicitly priced, businesses and households can connect rising fossil fuel costs to carbon pricing.

Regulations impose costs on businesses, but it’s more difficult for households to connect the impact for them.

For example, Quebec zero-emissions vehicle (ZEV) requirements for the manufacturers can impact the price of cars at the dealer.

Subsidy costs are hidden because the taxpayers broadly bear them.

Bold climate policies: transportation, climate-aligned finance, government procurement

What tools would be most relevant to reducing emissions now that consumer carbon pricing is dead due to its lack of public acceptability?

It will surely be a mix of policies, said all the experts interviewed. However, some policies have more impact than others.

Pineau said that shutting down Ontario’s coal plant was the most significant Canadian climate policy.

“The phase-out of coal-fired electricity generation in Ontario, completed in 2014, has had significant, measurable, positive effects on environmental quality, particularly concerning acid rain, smog and greenhouse gas emissions,” stated this report from Mark Winfield and Abdeali Saherwala at York University.

Pineau said a massive conversion from road to rail and maritime transportation would be another impactful climate decision.

“It would reduce 90 per cent of energy consumption and emissions related to transportation,” said Pineau.

“There would be gains even with diesel-fueled trains because you have two locomotives and 100 wagons replacing hundreds of trucks. The end goal would be to convert these trains to electricity, hydrogen, or biofuel,” he said.

This conversion would also give a significant economic boost through a public investment program, he added

“There are numerous climate regulations, subsidies, and fees. You can easily get lost trying to sort them. I would rather see more radical climate initiatives, like rail and maritime transportation conversion,” he said.

Creating new accountability for banks and pension funds also qualifies for a bold climate initiative, said Segal.

“It is the missing piece of Canada’s climate plan and strategy. Our banks and pension funds should be investing in environmentally productive ways for all,” said the climate finance expert.

Nearly 80 per cent of Canadians want new rules for the financial sector to align with climate commitments. “And most do not trust financial institutions to do it without new policies,” said Segal.

That is where the Climate-Aligned Finance Act, Bill S-243, comes into play.

Bill-243 aims “to make timely and meaningful progress toward safeguarding the stability of both the financial and the climate systems.” Senator Rosa Galvez champions it.

For example, the Climate-Aligned Finance Act requires the avoidance of carbon lock-in in all financial decisions.

“Carbon lock-in occurs when fossil fuel-intensive systems perpetuate, delay, or prevent the transition to low-carbon alternatives—a situation that can seriously imperil climate action,” according to the World Resources Institute, an American evidence-based institution.

Financing today a new fossil-fueled infrastructure with a lifetime of 35 years would take us to 2060. It would add new emissions now and keep adding them beyond the 2050 deadline for a carbon-neutral world. This would be a carbon lock-in.

The Climate Finance Act includes leveraging climate expertise and having at least one climate expert on the board of directors for major crown corporations and pension boards.

Segal highlighted how Canadians are getting frustrated.

Home insurance has become more expensive due to flooding and disastrous fires, and food prices are rising due to warming.

As a result, the housing affordability and climate crises are merging, making it a fairness issue.

“The next federal government needs to move forward with policies levelling the playing field between those paying the cost and companies and people. Aligning finance with climate goals is an essential part of these policies, with capping pollution from oil and gas and keeping a carbon price on high-polluting industries,” said Segal.

Climate policy is economic policy, added Curtis.

On the one hand, polluting solutions must cost more. On the other, cleaner solutions must be more effective and cost-effective.

“The impact of climate policies is not limited to reducing emissions. The economic benefits are part of the business case,” said the Pembina Institute director.

“The government has a role to play by being a market-builder,” she added. It can procure low-emissions and energy-efficiency emerging technologies to set the motion.

Having the government as a steady client encourages entrepreneurs to build supply chains and train people.

“That is how you bring down the cost for others to use those technologies and see ripple effects on emissions reduction,” said Curtis.

Climate philanthropy and non-profits’ strategy to adapt to the tax axe

Building a business case for climate policy is complex. So is climate storytelling.

“Most policies are difficult to describe and to explain,” said Eric Campbell, CEO of the Clean Economy Fund, a Canadian climate-philanthropy initiative.

“Climate philanthropy needs to be strategic with its funding,” he added.

As a result, there is a short game and a long game.

“In the short term, we must address misinformation about the cost of climate solutions and how they interact with affordability. In the long term, we must build a case reminding Canadians that the environment and the economy go together. Our economy comes from nature and a healthy environment,” said Campbell.

The Clean Economy Fund funds organizations like Clean Energy Canada and Efficiency Canada, doing analysis on the affordability of climate solutions for households.

“I did not expect this fight to be so dirty. We must think critically, not be critical,” said Cathy Orlando, Director of Citizens Climate Lobby Canada.

Orlando trains environmental non-profits to talk to politicians in an impactful manner.

“Politician is a tough job. There are good politicians in all parties. Activists should build relationships with them. It is not about treating them like your employees, forcing them to do our will. It is about advancing together,” added Orlando.

If carbon pricing is the most cost-efficient climate tool, should the environmental lobby still fight for it?

“I try not to get attached to the policy I fight for,” said Orlando. “I do not need to win carbon pricing. The end goal is to win a livable world.”

She added that it is not only a climate issue but also a human rights issue.

“The setbacks call for alliances with people you would not usually ally with. Climate non-profits should consider getting closer to groups standing out for human values,” she said.

Orlando’s ideal of concentrating on a “North Star” issue is wise, says Krystyn Tully, CEO of Entremission, a Montreal consulting company for social impact organizations.

She added that advocates should never think the fight is over because they won or lost.

“When a progressive lobby wins on an issue, we move on. When a conservative lobby loses, they don’t accept, and they continue to lobby to get legislation rolled back.

“That is how many effective environmental protection systems were dismantled when the champions thought they won,” said Tully.

So, what should environmental lobbies fight for now?

In recent years, many environmental organizations shifted their attention to the ground, mainly to the municipal level, where the programs are implemented, said Tully.

“The burning question non-profits is: should your staff drop everything to go back to working on federal policy or keep with the commitments to get more city councils to adopt climate adaptation or mitigation policies and accept not be influential on the federal stage?”

Also to be considered: Canada’s climate policies were implemented several years ago, added Tully.

“Those who contributed to their adoption are not necessarily ready to start a new fight. We need to see if fresh forces can take over. And if it would be the best use of their time at this moment in history.”

Lastly, environmental non-profits should take some lessons from right-wing think tanks, said Tully.

“Decades ago, they invested in researching and seeding collaboration with universities to build a knowledge base and develop policy concepts. They took a much longer view of how you create societal change,” she said.

“When I reflect upon my work and our sector’s work, the focus is always urgent. I never worked on a campaign with funding for 10 or 20 years. The roll-back on consumer carbon pricing stresses that we must build baseline knowledge around environmental care. Thus, non-profits won’t stumble, feel scared or intimidated when confronted by catchy slogans,” concluded Tully.

A recent report from the McGill University Centre for Media, Technology, and Democracy suggests an emergent tendency: climate obstruction. Climate delay narratives—messaging acknowledging climate change but downplaying urgency and viable solutions—influence public perception and policy action. While three-quarters of Canadians agree that climate change is real, fewer than half believe it directly affects their lives today.