Children spearhead change in Worst Child Labour countries

Why It Matters

Evidence from Bangladesh and Nepal shows that children can understand their exploitation and offer meaningful solutions. Engaging them is critical to developing more effective strategies to combat the worst forms of child labour.

In Dhaka, Bangladesh, 15-year-old Pavel starts his day at 6 a.m. by taking the bus to his dangerous job in a leather factory.

At 8 a.m., he reaches his destination, where he will spend the day carting leather by hand to and from vehicles under the blazing sun. He will suffer shoulder pain from carrying heavy loads on his head. His hands will bleed from cutting the leather with knives, blades and scissors. He will breathe in the thick leather dust with unprotected lungs.

“This is a risky job,” he said.

“I need to process the leather. After that, I need to carry the processed leather on my head to load the vehicle with leather. I need to unload the vehicles. These tasks are very difficult. Sometimes, I do toggling under the direct sun. Each day, I need to work for two to three hours under the direct sun.”

His monthly income is Tk.7,000-8,000 ($79-90). His bosses are verbally abusive and also force him to run their errands.

Pavel had little choice but to become a labourer when his mother became seriously ill, which cost the family a couple of thousand dollars in treatment.

His elder brother then disappeared, which deprived the family of extra income. His father is a rickshaw driver. The family is a victim of financial fraud and owes years of rent to their landlord. They can’t return to their village unless they clear the debt, or they risk violence.

The leather supply chain in Bangladesh consists of 107 steps. One hundred three of them involve child labour, including the worst forms of child labour (WFCL), defined by the International Labour Organization as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.”

While Bangladesh’s formal and export-oriented leather sector is relatively regulated, the informal sector relies on WFCL. Located in Dhaka’s slums, many factories are not more than 200 square feet in size and employ around ten workers, including children.

These businesses sell their products to medium—and large-scale buyers destined for the billion-dollar local market. These products involve children’s harmful work, such as preservation, tanning, dyeing, drying, and sewing.

Rama, 17, lives in Kathmandu, Nepal. She works 14 hours a day. After waking up around 10 a.m., Rama starts her shift as a beautician at her home-based parlour. “I like my work at (the) beauty parlour as I believe I am skilled at this work,” she said.

However, the NPR 25,000 ($250) she earns from the parlour, which she opened with the help of a local non-profit organization, is not enough. Rama supports herself and her sick mother, who’s no longer able to work. Her father left the family long ago.

To earn more, she works as a dancer at a bar. Her shift starts at 7 p.m. and ends past midnight. The dance bar earns her around NRP 20,000 ($200).

Rama doesn’t like the environment at the dance bar. She’s uncomfortable with the customers’ smoking and drinking and is pressured to partake in these activities. Men sexually harass her. She’s not allowed to take days off and has to dance in revealing clothing and high heels, even when on her period.

Dance bars are part of Kathmandu’s adult entertainment sector – massage and spa venues and folk dance bars called dohoris – and the related and less sexually explicit hospitality sector, including small-scale hotels and informal eateries called khaja ghars.

Nepal’s adult entertainment sector has grown since the 1980s due to societal changes. There is an increased demand for male entertainment in urban spaces, especially with the rise of rural-urban male migration. Many businesses in the sector are located in Kathmandu’s busy commercial and tourist centres and employ underage girls.

CLARISSA collects stories from 800 youth

Pavel and Rama’s stories are just two of 800 life stories collected in Bangladesh and Nepal by Child Labour: Action-Research-Innovation in South and South-Eastern Asia (CLARISSA).

CLARISSA, funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office and delivered by the Sussex-based Institute of Development Studies (IDS) in partnership with local Nepali and Bengali organizations, was a five-year research-for-development program from 2019 to 2024 focusing on the systemic drivers behind WFCL in Bangladesh’s informal leather supply chain and Nepal’s adult entertainment sector.

CLARISSA aimed to spark potential systemic changes in the two sectors by generating evidence and developing innovative solutions through participatory action.

Co-led by Dr. Marina Apgar, co-director of the Centre for Development Impact at the Institute of Development Studies, CLARISSA’s origins were relatively typical: a call for proposals by the funder and a consortium response. Unlike most such projects, however, an academic institution rather than an NGO led the implementation.

Unsurprisingly, an academic institute like the IDS firmly anchored the program in a research- and evidence-based approach to generate solutions for WFCL. The research component was IDS’s value-add since NGOs typically lack such capabilities.

But arguably, the consortium’s most valuable contribution was not so much its solutions as its innovative approach to generating solutions.

A radical approach to innovation

“We had lots of debates in the program. What does innovation mean? Is it something that’s never been thought of before anywhere? Or is it something that’s never been tried in that context?” said Apgar, who also served as CLARISSA’s lead evaluation researcher.

Based on those reflections, the program defined innovation as something “novel to the people in place,” Apgar said.

CLARISSA’s novelty was to make child labourers and businesses who employ them the principal generators of reflection, evidence, and action. The approach, known as systemic action research, was rooted in the idea that “everybody is a change agent,” Apgar said.

The inherently participatory paradigm assumes that marginalized populations can make sense of their lives and identify solutions to their problems.

The simple yet bold proposition upends two assumptions: that children don’t possess the intellectual capacity to understand what drives them to WFCL and the ability to advocate for their rights, and that employers are perpetrators who don’t want to address WFCL in their industries.

“Most innovation literature focuses more on the what and less on the how,” said Apgar. For CLARISSA, “generating ideas through a participatory process was essential,” she said.

The program had an insider perspective with children and businesses generating an understanding of, and solutions to, WFCL. It provided pathways to understanding and change that typical NGOs with outside experts don’t possess.

Building trust before conducting research a necessary step

Getting children like Pavel and Rama to tell their life stories required trust-building. “Working in those communities was very challenging at first, especially during COVID-19, as many people were out of work and struggled to afford basic needs,” said Sayma Sayed from the Grambangla Unnayan Committee, a CLARISSA implementation partner in Dhaka.

“Initially, we did not mention we were conducting research. Instead, we built relationships—talking with children, parents, employers and identifying influential community members,” she said.

“Once we established trust, we explained our research intentions. With the support of community leaders, we reached out to more children. Trust grew as the community became familiar with us and saw we posed no threat,” she said.

“We communicated clearly with parents and obtained consent,” she added, noting parents were invited to their office to explain the project and encouraged to ask questions.

Creating a safe physical space for children was also paramount. “It wasn’t feasible for children to come to our location, so we set up action groups in specific, convenient clusters,” said Kriti Bhattarai from Voice of Children, a CLARISSA partner in Kathmandu.

“We partnered with like-minded organizations within these clusters to create a safe and familiar space. It made it easier for the children to attend meetings,” she said.

Like in Dhaka, building trust with children in Kathmandu took time. “They were understandably skeptical of outsiders,” Bhattarai said.

Children understand their lives

The children’s primary activity at the start of the project was collecting their life stories.

“Unlike structured interviews, these were open-ended life stories where participants shared their experiences in detailed, sometimes lengthy narratives,” Apgar said.

The goal was to analyze the stories to identify the various interrelated factors that led children to WFCL.

The story-collection process is an essential insight into CLARISSA’s child-centric nature, said Ranjana Sharma from Children & Women in Social Service, another CLARISSA partner in Kathmandu.

“The children were the ones who provided their stories, and we also trained them to collect stories from their peers. The 800 life stories were analyzed by the children—not by adults. We were only there to facilitate,” she said.

“The children conducted observations, noting how they lived in their neighbourhood and whether any factors in the community pushed them into different forms of child labour,” said Mushtari Muhsina, who worked at the time with Terre des Hommes, another CLARISSA partner, in Dhaka.

“The stories were transcribed, and the children read them to identify the causes that led them and others to join the workforce and the consequences that followed,” she said.

“These children have no money, so they are forced to work. However, after analyzing the data, the children came to understand—and we also observed—that while economic hardship is a significant factor, other causes are also connected,” Muhsina said.

The lack of parental supervision, either due to a lack of care or parents’ inability to make time for their children due to work, turned out to be a significant factor, she said.

“Children, left unsupervised, may start taking drugs or spending time on mobile video games. Seeing this, some parents send them to work in factories to earn money,” Muhsina said.

“There are limited education opportunities. There are no government high schools, and private high schools are too expensive. Children often drop out after primary school and end up idle at home, eventually going to work in factories,” she said.

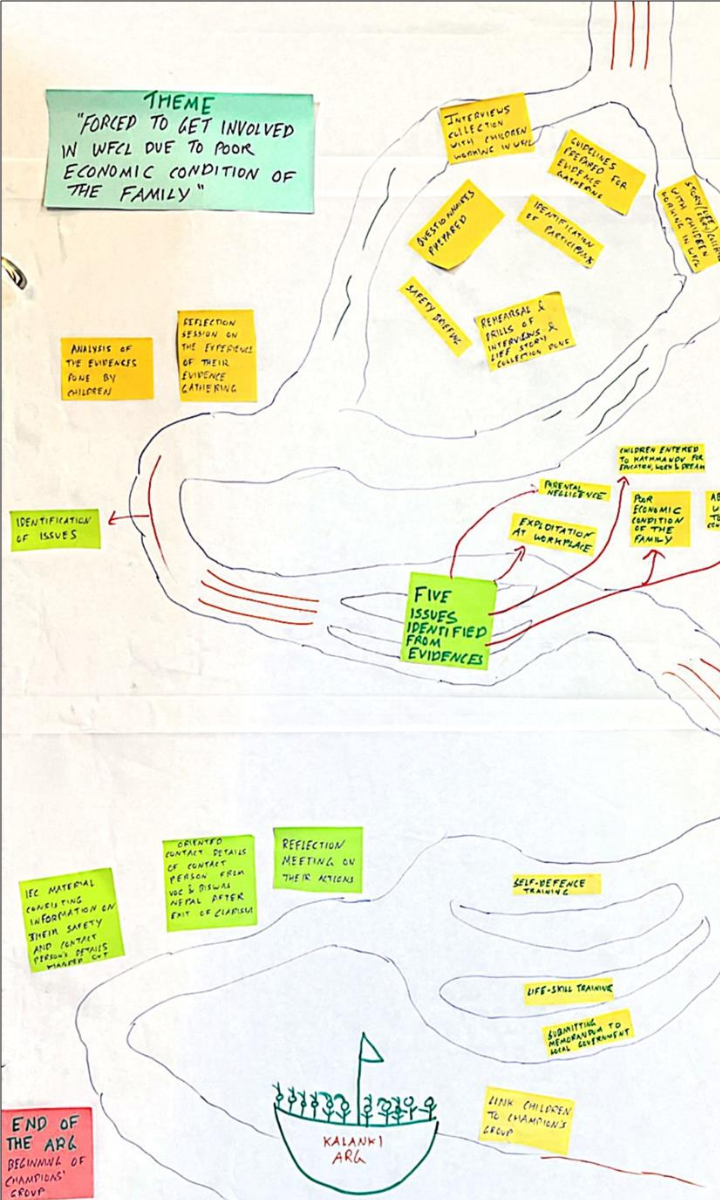

The children mapped out each story and produced a large flow chart or systems map.

“The maps illustrate, for example, a child’s life story starting with a major incident like a flood in their area. The child would create a box indicating this event. Then, they might show the following significant incidents—such as their parents losing their farming land due to the flood—linked with a line to indicate the connection,” Sharma said.

“Following that, they would have another box for the next step, like having to leave for Kathmandu because there was nothing to eat. Another box might indicate staying at a sister’s place,” she said.

“The maps help distinguish between simple linkages—events connected by a cause—and more complex cause-and-effect relationships,” Sharma said.

This approach was central to developing a theory of change. “This often-overlooked process involves carefully considering how to understand the dynamic in question,” Apgar said.

“The CLARISSA team faced significant challenges with this, as staff were accustomed to a more traditional NGO mindset, which often leads to a premature focus on solutions rather than a thorough exploration of the underlying issues,” she said.

Overall, in Bangladesh, the children highlighted the following causal factors behind the worst forms of child labour: workplace safety, inability to afford schooling, social norms, debt, child marriage, and family negligence. In Nepal, they identified poor economic conditions, addiction, homelessness, and lack of birth certificates, among others.

Engaging, not accusing, businesses

Alongside children, CLARISSA facilitated reflection among business owners.

It was tough initially. “No one was willing to acknowledge child labour existed in their sector,” said Bhattarai. The refusal was because previously, “some programs had focused on targeting employees and turning them against the owners, portraying the owners as villains,” said Sharma.

“It took me about 14 to 16 meetings to convince them,” she said.

But when owners “learned about CLARISSA’s approach—that we weren’t there to accuse them of wrongdoing but rather to help them understand legal requirements and the importance of compliance—the owners began to open up,” said Bhattarai.

“This shift in perspective allowed for more productive engagement with the business owners. They started to share the realities of their businesses, acknowledging child labour was present and providing details about the numbers of children involved,” she said.

As business owners opened up, CLARISSA’s staff used several methods, such as shadowing, to spend entire days with the businesses to observe how they operated.

“This approach provided detailed evidence. We’re dealing with small, highly informal, and often hidden businesses. Few people have been able to get behind the scenes and truly grasp what’s happening,” Apgar said.

Similar to children’s tales, stories about how and why businesses hire children allow the mapping of relevant causal factors.

For example, “many businesses, such as khaja ghars, are located near transportation hubs. Children arrive from their villages hungry. They go to snack houses looking for food, which leads to a conversation,” Sharma said.

“The owner, often a woman, would ask, ‘Why did you come here? What are you doing?’ The child would respond, ‘I need work. I have no one to take care of me.’ Out of sympathy, the woman would respond, ‘You can stay and work for me. I’ll provide you with a place to stay and food,’” she said.

“Some of these business owners were child labourers just a few years ago,” said Apgar.

“They are at the bottom of the supply chain, operating with thin margins and struggling. These are not people building empires through exploitation, unlike the more sexy stories you often hear about child labour, forced labour, or modern slavery,” she said.

In Bangladesh, business owners identified the relationship between informal and formal enterprises, the lack of health services for workers, and the lack of collective action capacity among businesses to address their marginalization and informality as the leading causes behind WFCL in the leather industry.

In Nepal, the causes included the lack of documentation systems, business registration, and a similar lack of collaboration between businesses as in Bangladesh.

Children take action

After analyzing the stories, the next step was to take action. The children proposed and undertook more than 70 actions across the two countries to address those causes.

In Dhaka, “in one location where children work on leather drying and processing, a toilet was built because children and women had no access to such facilities. This lack of access led them to avoid drinking water while working, resulting in various health issues,” said Mushtari.

In another example, the children established a club in Dhaka to train their peers to make bead ornaments.

“Children advocated with a private school authority to arrange special schedules for working children, such as evening classes, or on Fridays, a holiday in Bangladesh. Under the regular schedule, these children couldn’t attend school due to work. The children also negotiated for reduced admission fees. The local school authority agreed to charge less for working children,” said Mushtari.

Changing attitudes required patience and creativity rather than confrontation. For example, in Dhaka, “where children work in leather factories that make gloves, a group focused on workplace safety as their key issue,” said Apgar.

“A small group started wearing safety equipment to work as a way to demonstrate that a safer approach was possible and to generate interest among others. This eventually led to more of their peers becoming interested in wearing the equipment, resulting in the employers agreeing to provide safety equipment for all,” she said.

In one neighbourhood in Kathmandu, children “organized a workshop with business owners focused on cybersecurity and mental health issues. The participants shared the problems they faced due to a lack of awareness about cybersecurity,” said Bhattarai.

“For example, they would receive expensive mobile phones as gifts from customers but didn’t know how to use them properly. They would connect with everyone on social media, which led to problems such as blackmailing of young girls,” she said.

Moreover, the children “suggested such activities should also be conducted in government and community schools. Students at these schools, often from low-income families, risk ending up in vulnerable sectors later in life. It could be a preventive measure if they are well-informed about cybersecurity and its impacts,” Bhattarai said.

The children “spoke to the teachers and organized other activities, such as dramas,” she added. “They addressed issues like birth certificates, citizenship, and how deprived children end up in vulnerable situations.”

In addition to workplace safety and education, the children wanted to improve their localities. In Dhaka, they “identified areas in their neighbourhood that were unsafe for them, particularly girls. They advocated for their safety with local government and community leaders,” said Mushtari.

“The children negotiated with a local commissioner to increase police patrolling in areas where drug selling was prominent and posed a threat to girls moving around. Street lighting was also improved,” she said.

“One of the innovative aspects of how solutions emerged (in Dhaka) was that boys had the opportunity to see the experiences that girls went through concerning toilets and other safety and health-related issues. It led to boys suggesting solutions,” Apgar said.

“The innovation wasn’t just about a different way to think about the safety challenge for girls; the suggestions came from boys. In that sense, you are also potentially shifting social norms,” she said.

The actions initiated by children benefited those who did not participate in the program. In Kathmandu, “a stepfather was abusing a child who was not part of the reflection groups,” Bhattarai said, but when “a peer learned about this, she reported it to a teacher, which exposed the issue, and the child was taken to a safe home. Situations like these came to light because we facilitated the environment,” she said.

Businesses take action

Alongside children, business owners addressed the causal factors highlighted during their reflections.

In Kathmandu, they were generally “less innovative with their solutions,” said Apgar, noting many focused on administrative actions like improving bookkeeping to keep track of underage employees.

“The owners in the adult entertainment sector were particularly concerned about their image. One could argue they were trying to make themselves look good, but for many, a sense of identity and dignity drove the desire to clean up their sector,” she said.

“This is an example of a process that might not have emerged from other interventions,” said Apgar.

Business associations in the adult entertainment sector in Kathmandu were inactive when CLARISSA initiated dialogue with the owners. However, the owners later realized they could “address many of their issues if they revived the associations,” Bhattarai said.

“With that in mind, some of them organized an AGM, elected new members, and provided training to their members,” she said.

Businesses’ initiatives to regulate their sector yielded concrete results in Kathmandu. Massage and spa businesses, for example, decided to add the minimum legal age of 18 to their code of conduct.

“They established a rule that no massage or spa business would hire anyone under 18. They made the code of conduct visible so everyone could see,” Bhattarai said.

“Additionally, the associations initiated compliance visits to monitor the businesses. If they found anyone hiring a child, the association would question them. The business owners took these actions,” she said.

Businesses began issuing appointment letters, “which also verify ages, as employment is only allowed for those 18 and older,” Bhattarai said.

In Dhaka, business actions resulted in more projects. In one locality, leather factory owners established a healthcare centre for their staff. In another locality, they established a job training centre for children. In another area, employers contributed to an educational fund for children.

“Employers who previously only thought about their profits now considered the welfare of children. This shift in mindset was the main impact of this project,” said Sayed.

Power of the collective

In addition to the concrete material changes, children who participated in the program benefited intangibly in many ways.

“The children felt valued and heard, as their opinions were listened to by the facilitators, and the facilitators allowed the children to drive the analysis process,” Apgar and her colleagues wrote in their project evaluation report.

Children working with other children fostered trust, allowing others to share their experiences openly, they added.

“Hearing stories from their peers triggered empathy as they developed a deeper understanding of other children’s lives. By hearing details of their peers’ lives, they also saw their own experiences reflected in their peers’ stories, and this triggered in them a sense that they were not alone,” Apgar and her co-authors wrote.

Businesses equally understood the power of collectivity.

In Kathmandu, dance bar associations “saw the importance of sharing their knowledge and experiences with a wider group of business owners so that they could also benefit by following legal provision and thus, together, could clean up the whole sector,” they wrote.

“The improved relationships between businesses is what further fuelled the pathway of businesses who were less organized and only beginning to organize due to extreme marginalization to shift their own practices and move towards collective action across the sector,” they noted.

Collective agency over expert view

According to Apgar, international development organizations, including Canada, can learn from CLARISSA’s approach.

The program’s main takeaway is that innovation goes beyond just the solutions. More profoundly, it is “the process through which solutions are developed,” Apgar said.

For CLARISSA, the innovation was participation in a sector where participation did not exist. This included empowering children to share their stories and collaborating with businesses rather than confronting them.

The reflections and actions from this process helped “tell a story about potential,” Apgar said. It showed that “pathways to systems change are more about motivating the energy, agency, and potential that already exist in a system,” she said.

Participatory action and research are adaptive. Apgar and her colleagues previously used this approach to peace-building in Mali. The participatory paradigm can foster localization in any context. It can de-centre NGO expertise from the Global North working in the Global South to make space for community-led development. “The need for an expert view is so strong in our world. But there’s overwhelming evidence from this program about the power of collective agency,” Apgar said.

For organizations working on children’s issues, whether child labour or other topics, CLARISSA proved that “children have their views about what matters to them and can engage in complex, nuanced analytical work,” Apgar concluded.