Canada’s Social Finance Fund’s first investment champions outcomes financing

Why It Matters

Over the last decades, a vast amount of federal money has been injected to address socio-economic issues. However, there have yet to be outstanding successes in changing the trajectory of socio-economic indicators, such as overall health, education and environmental issues. Outcomes financing might be a valuable tool to address some of these challenges.

The first investment from Canada’s Social Finance Fund is a $10 million venture supporting a unique type of impact investing called outcomes financing.

BOANN Social Impact, one of the three managers of the SFF, said Raven Indigenous Outcomes Fund (RIOF) will be the first recipient.

Another way to tackle society’s challenges

Traditionally, the way to tackle societal challenges is by creating programs that governments design and then provide grants and contracts to social enterprises, non-profits, and charities to deliver them.

These programs are generally monitored based on quantifiable outputs, such as: how many homeless people are sheltered? How many drug users are enrolled in addiction treatment programs? How many unemployed people are enrolled in training programs?

“There are a lot of extremely well-intentioned people in government, said Jeff Cyr, co-founder of Raven Indigenous Capital Partners (RICP), which launched RIOF. “I’ve met many of them when I worked there.”

But government programs are prescriptive and systematically underfinanced, he said.

Systemic change needs more money and more flexibility, said Cyr, along with community involvement.

“If you want systemic change, you need to engage the community,” echoed Stephen Huddart, President of the McConnell Foundation, when it invested $450,000 in Canada’s first outcomes financing initiative in 2017.

The difference between social impact bonds and outcomes financing

The idea of tying financing to results is not new, as social impact bonds have been available in Canada for many years.

Canada’s first social impact bond was Saskatchewan’s Sweet Dreams program, created in 2014. Sweet Dreams supported vulnerable young mothers and their children by keeping 22 kids in the care of their mothers for six months.

The bonds developed during those early days would lessen the risk of babies ending up in government-funded care. The initiative was a success, and it is now a regular program from Saskatoon’s non-profit EGADZ.

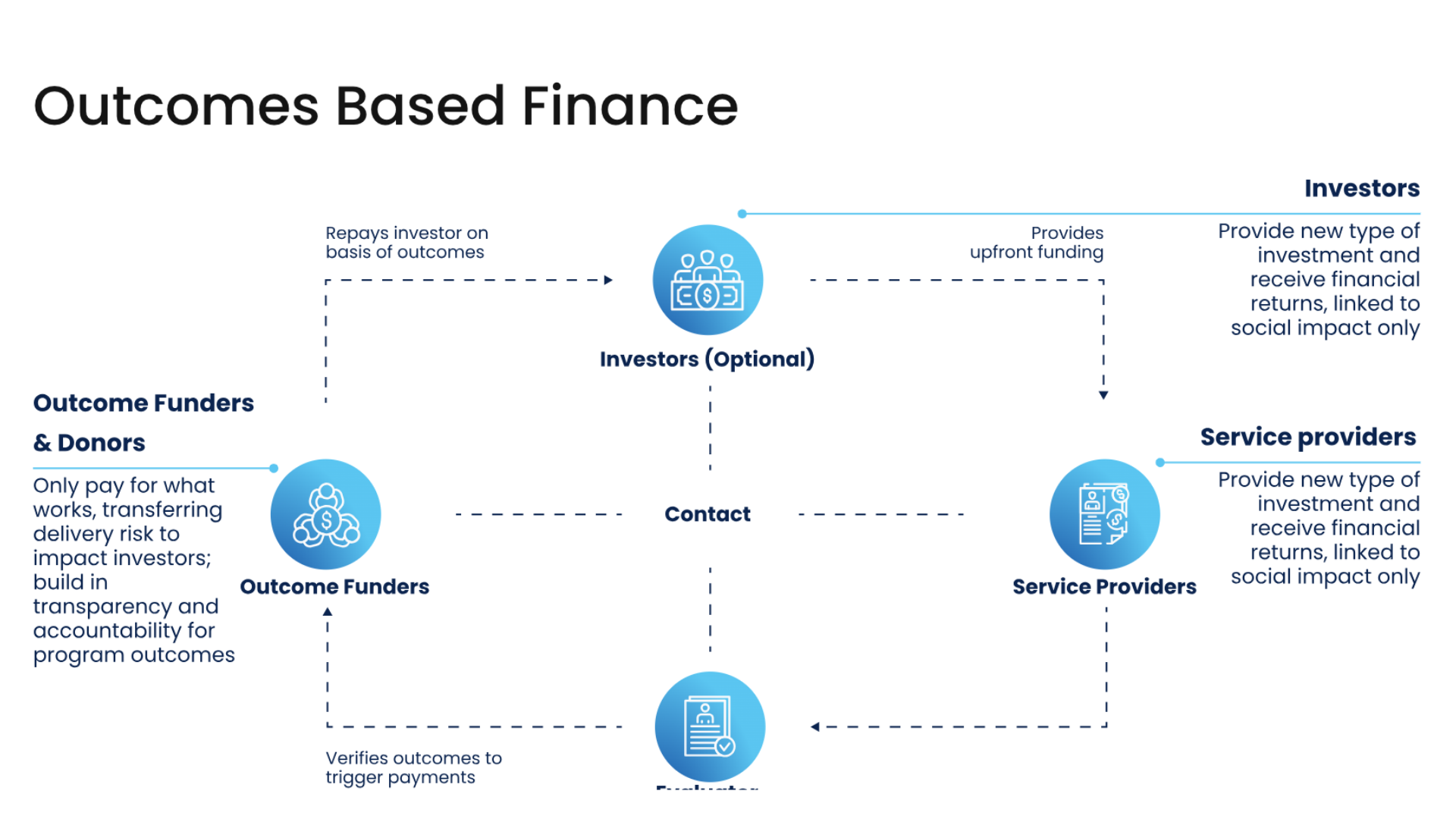

Both social impact bonds and outcomes financing rely on a social-purpose organization to implement an innovative approach to a problem. Investors finance the project, and then the outcome purchaser, usually a government agency, pays back investors with a return if the outcome is achieved.

However, the ideas behind most social impact bonds generally come from the government or some prominent money provider, said Cyr.

Outcomes financing comes directly from the community.

Community priorities inform and drive the projects; this way, accountability is not just to investors and outcomes buyers but also to community stakeholders, said Cyr.

Community priorities are included in the community-driven outcomes contract, said Amanda Mayer, COO and program director for The Lawson Foundation.

As an impact investor, the Foundation contributed to Canada’s first Outcomes financing initiative with the McConnell Foundation.

This contract identifies the outcomes a community desires to solve the targeted problem. A local organization is contracted to deliver those outcomes. When done, a third party confirms the outcomes according to pre-determined indicators. Then, the outcome purchaser repays the investors according to the contract. The payment may be fractioned according to key delivery moments.

This contract identifies the outcomes a community desires to solve the targeted problem. A local organization is contracted to deliver those outcomes. When done, a third party confirms the outcomes according to pre-determined indicators. Then, the outcome purchaser repays the investors according to the contract. The payment may be fractioned according to key delivery moments.

Canada’s first outcomes financing initiative

Canada’s first outcomes financing initiative happened in Manitoba’s Fisher Cree and Peguis First Nations in 2017.

The pilot project was an energy transition and resilience initiative, where ground-source heat pumps were installed in 124 homes, with more than $4 million injected into the local economy.

The outcomes were lower utility bills, job creation, and reduced greenhouse gases emissions.

Raven Indigenous Capital Partners was the financial intermediary, with Winnipeg Aki Solutions Group as the outcomes provider and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation as the outcomes purchaser.

Finding an outcomes purchaser is always a critical step, said Mayer. The purchaser and investors need to buy into the outcomes financing concept and the proposed solution.

Regarding the energy transition project, investors came from the Communities Foundation of Canada, the McConnell Foundation, and the Lawson Foundation.

This project had a positive impact on the beneficiaries’ quality of life. The 124 households saw their energy bills reduced by 50 per cent, resulting in $1,000 saving annually.

Since the Aki project met its outcomes, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation paid investors back with a four per cent return.

In its first throne speech on Nov. 21, newly elected Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew stated his government’s intention to invest in more geothermal home conversion.

“It happens because of what Aki Energy demonstrated is possible,” said Mayer.

So far, the Manitoba government has announced these conversions will be implemented using the affordable oil-to-heat pump program.

Proof leads to more possibilities

Once a proof-of-concept is established through outcomes financing, like Aki’s project, there are three possibilities, said Marie-Josée Parent, senior director at RICP.

The first is integrating the initiative into the government’s regular program.

The second option is launching phase two of the initiative, still using outcomes financing.

A third option also involves scaling, but with the community becoming 100 per cent owner of the initiative. It can rely on the same partners and outcomes financing or go a different direction.

A third option also involves scaling, but with the community becoming 100 per cent owner of the initiative. It can rely on the same partners and outcomes financing or go a different direction.

A multi-stakeholder Solutions Lab to craft the solution

The Aki energy conversion project was designed by the Energy Solutions Lab, which is a risk-management mechanism to help ensure outcomes, said Cyr.

Each project begins with laboratory meetings where community representatives and financers discuss the problem. Together, they co-design the intervention and identify the content of the community-driven outcomes contract, said Cyr.

However, relationship-building challenges need to be considered.

To help advance reconciliation, Indigenous communities must be able to lead and participate in the entire process, said Meyer.

The Aki pilot project was more than an energy efficiency and utility bill reduction. It was a job creation and poverty reduction initiative, says Shaun Loney, co-founder of Aki Solutions Group, who also ran for Winnipeg mayor in 2022.

“We train people in our community to become installers. They can have a career quickly and be experts and heroes in their communities. So the government sees fewer people on

social assistance,” he said.

In this way, outcomes financing becomes a tool of decolonization, said Loney, who echoed every panel member’s opinion at the recent Outcomes Finance Summit in Ottawa, held Nov. 15.

In this way, outcomes financing becomes a tool of decolonization, said Loney, who echoed every panel member’s opinion at the recent Outcomes Finance Summit in Ottawa, held Nov. 15.

It is all about procurement, not funding.

“A lot more government money goes into procurement than funding,” said Loney. “Indigenous providers want to be recurrent actors in the procurement process and benefit from this equal relationship.”

Why outcomes financing is suited to Indigenous reality

“There has not been outstanding success in changing the trajectory of economic indicators for Indigenous people.” said Rebecca Waterhouse, Principal at RICP. “Despite large buckets of spending over many decades, the Indigenous communities find themselves in a cycle where very critical issues are not being addressed,” she said.

“Colonization is about extracting value from people and the land,” said Cyr. He sees outcomes financing acting as medicine in the economic system. “Outcomes financing changes the direction of money. It gives Indigenous communities the tools to become stronger and more resilient,” he said.

“Colonization is about extracting value from people and the land,” said Cyr. He sees outcomes financing acting as medicine in the economic system. “Outcomes financing changes the direction of money. It gives Indigenous communities the tools to become stronger and more resilient,” he said.

Although outcomes financing can be relevant to Indigenous communities’ needs, significant challenges still exist, said Waterhouse.

She said the first is community readiness, adding time is needed to build capacity and structure the projects.

“Indigenous community and Indigenous service providers start from a different place of readiness and wealth,” she said.

There are also fewer non-profit, charitable, and other service providers in the Indigenous community than in non-Indigenous communities.

“So it takes longer to structure programs, and there is some capacity work that we have to do along the way,” said Waterhouse.

In addition, some communities are struggling as they jump from one crisis to another. Thus, some outcomes financing projects need a community engagement and development phase, supported by grants, and the seconding of technical expertise to social-purpose organizations.

“To create solutions together, you must be patient,” said Waterhouse.

The next step: a $25M health outcomes financing initiative

In Canada, if you are a First Nation person under the age of 25, you have an 80 per cent risk of developing Type 2 diabetes in your life.

First Nations Manitoba children are 25 times more likely to be diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes than other Manitoba children, according to a 2020 study by the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy.

“In some communities, like the Anisininew, 25 per cent of the population over the age of seven is affected by Type 2 diabetes,” said Parent. For the rest of Canadians, the rate is between four per cent and seven per cent.

Aside from the direct impact on the quality of life of those suffering from this disease, there is indirect collateral damage. “Our elders die earlier,” said Parent.

“It prevents cultural transmission.”

In 2019, two years after the launch of the Aki project, RICP convened an Indigenous health solutions lab in Winnipeg. Health experts and First Nations representatives put their heads together to imagine a path for reducing diabetes rates and the conditions associated with this chronic disease.

The first phase will cover four Anishinaabe communities in Manitoba. The service provider is the provincial health authority serving the members of those communities, the Four Arrows Regional Health Authority.

“We recognize the efforts already being deployed by health authorities,” said Parent. However, these efforts are sporadic and insufficient to reduce the diabetes crisis, and residents of some communities need to fly to Winnipeg for treatment or consultation. Yet the annual budget for this is $80,000, which barely covers the salary of a full-time employee and some part-time resources.

A solution rooted in the cause of the problem

The disproportionate prevalence of Type 2 diabetes among First Nations peoples is multifactorial, said Parent.

The impact of colonization and the subsequent transformation of lifestyles is dramatic. “Communities travelled over large territories and led very active lifestyles,” said Parent.

These lifestyles provided access to healthy food. Today, food availability for many First Nations boils down to “processed foods sold by retailers holding a near-monopoly, and prices are disconnected from consumers’ socio-economic realities,” said Parent.

“The health initiative is structured around the roots of the problem,” said Parent. Medication will always be part of the treatment. Still, lifestyle changes contribute to preventing and reducing symptoms, she added.

The pilot project, planned for three years, includes health centers in the four communities. Some existing facilities will host those centers; some must be built.

The project’s 800 participants, 200 in each community, will be accompanied by health coaches teaching them to change their life habits for lasting results. The program is co-designed considering First Nations’ and the West’s best modern practices.

The outcomes will respect both traditions, said Parent. For example, blood sugar rate is a standard indicator of a patient’s health and will be part of the desired outcomes.

However, the success will extend beyond clinical outcomes to include mino-bimaaduziwin, which will also be measured. It means “a good life.” According to Parent, participants will judge if they feel the change they implemented holistically improved their lives.

The success factors

The Lawson Foundation is investing in this outcomes finance health initiative. However, it will differ from their contribution to the Aki energy initiative.

“We will invest in a fund made of multiple underlying community-driven outcomes contracts,” said Meyer.

Creating a fund allows Raven to multiply and scale outcomes financing, but it’s unknown how investors will react to the new venture.

Education is critical, said Cyr. The Canadian outcomes financing ecosystem is emerging. Investors chose Raven venture capital without worrying about the risk, he said.

“But they reacted to our new outcomes finance fund by saying, ‘Woah! That is risky!’”

Outcomes financing is not going to replace everything, said Waterhouse, as it needs a particular set of realities to make it happen.

“You can’t replace pension benefits by having an outcomes plan. There are things the government must do and will continue to do,” she said.

Outcomes financing is most relevant in two particular situations, said Derek Ballantyne, CEO of BOANN Social Impact.

First, when there is a desired public policy outcome, the model to deliver it has yet to be established. Methods and approaches need to be pioneered, giving those providing the results more flexibility.

Second, when a community has more than one objective, the objectives cross the boundaries of sponsoring government entities. Outcomes financing is a way to cut through without worrying about which jurisdictional lane you’re in.

What would help outcomes financing get more traction?

The forthcoming report “The State of Outcomes Finance in Canada,” co-authored by the Sorenson Impact Institute and the Raven Indigenous Impact Foundation, suggests creating a Canadian outcomes purchase fund to influence the government procurement process.

Due in February 2024, the report also suggests enhancing support to service providers to refine their governance. This would raise the number of service providers who qualify for outcomes financing initiatives.