Canadian community groups take hate-reporting data collection into their own hands

Why It Matters

Some historically marginalized communities do not trust police services and often don’t report hate crimes and incidents. Community organizations step in to fill that vital information gap.

“Did I hear correctly?” Mifrah Abid remembers asking in a Kitchener, Ont. DriveTest Centre last year after a woman loudly exclaimed that there were too many brown people in the waiting room.

Abid was shocked at the woman’s comments. It was a busy day, and she couldn’t find a staff person to report the woman’s behaviour.

She confronted the woman and told her she was being rude. Before she knew it, the woman lunged at her. In a panicked state, Abid pulled out her phone to record the attack in a video that would go viral.

The person who recorded the incident on their phone asked to share it with Abid.

Shaken, she couldn’t remember her phone number.

“My brain just kind of froze,” she said recently, nearly a year after the racist encounter.

Abid, who works for a non-profit called Coalition of Muslim Women of Kitchener-Waterloo, didn’t think she would end up in a situation she helps others navigate, so she decided to take her story public.

“I wanted to destigmatize victimhood,” Abid said.

“I wanted to call myself a victim so that people who don’t have much privilege feel comfortable with that idea… to encourage people to report.”

Abid has a good relationship with local police because of her work with the coalition, so she felt comfortable making the call to report the assault, she said

But she and other workers who serve marginalized communities know very well that not everyone will go to the police to report a hate-motivated incident because of a history of tense relationships with law enforcement.

Statistics Canada’s annual police-reported hate crimes report is often the only data available on national hate crime trends. In Statistics Canada’s most recent data, hate crimes increased by 7 per cent between 2021 and 2022 nationwide.

Still, there are gaps in those national numbers because of under-reporting and the exclusion of incidents that do not qualify as criminal, said Irfan Chaudhry, a hate crimes researcher at MacEwan University in Alberta.

Most police services collect data about crimes motivated by hate, which doesn’t include hate incidents, discrimination, hate speech, or any other incident that is not criminal. Some police services also collect non-criminal hate-motivated incidents, but there is no obligation to report that data to Statistics Canada.

“So, that’s why many community groups pulled together different resources to help to funnel … just the space for documenting different forms of hate communities experience,” Chaudhry said.

What happened to Abid was classified as an assault, and she went to local police. However, for others who do not feel comfortable going to the police, the Coalition of Muslim Women of K-W can help.

Anyone in the Waterloo Region who experiences an incident of hate or discrimination based on race or religion can anonymously report the incident through the coalition’s website, in person, by phone, email, WhatsApp and even voice notes using multiple languages.

“This is a community-based system. We are from that community, and folks are going to be really comfortable coming to us and reporting,” said Sarah Shafiq, director of programming and services at Coalition of Muslim Women K-W.

The idea is to make the reporting process accessible and approachable, she said.

People can also request additional support, such as counselling, help going to police or legal assistance.

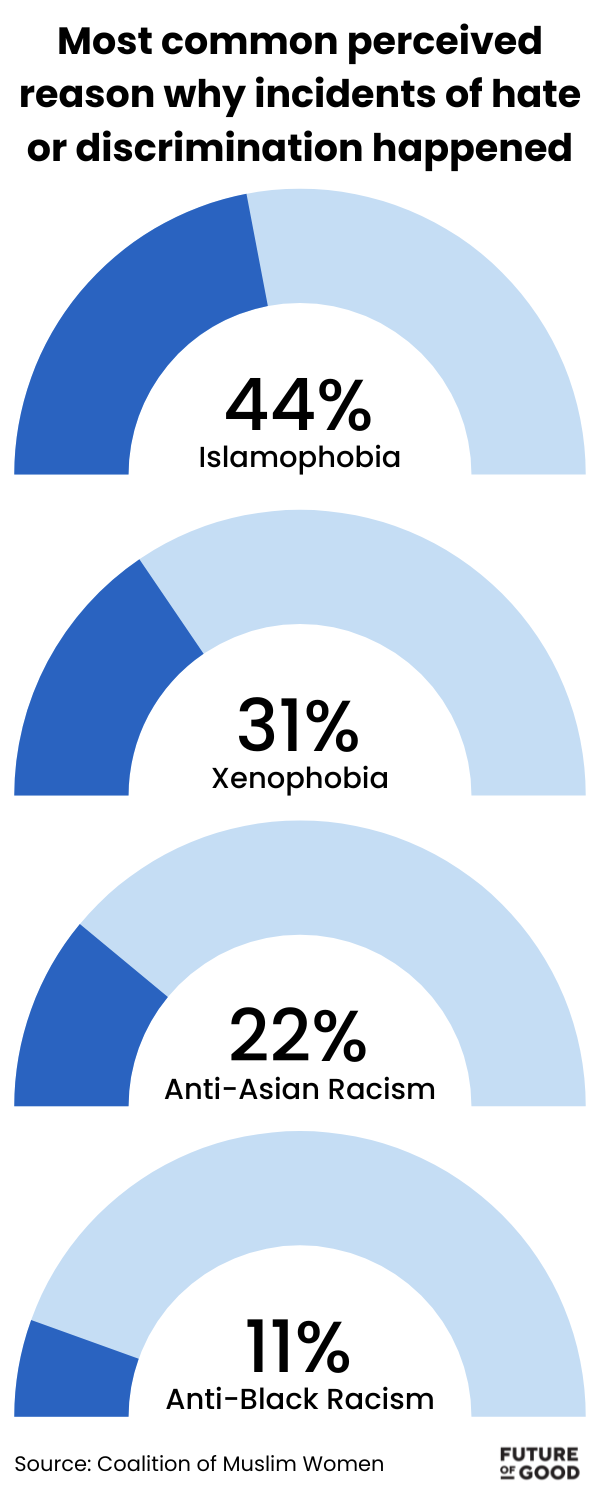

The coalition pooled its data through its Hate or Discrimination Documentation and Reporting Service, which included hate crime data from local police in its first “Snapshot of Hate” report.

In 2022, the coalition received 97 reports of hate. Of those incidents, 34 people chose to remain anonymous, and 64 decided to connect with support.

About 30 per cent of people reported incidents through the coalition’s website, while the rest went directly to coalition staff, highlighting the importance of community trust in this process.

Community-led hate reporting gives insight into trends

While the coalition’s hate-reporting tool is focused on racism, anti-immigrant sentiment, Islamophobia, and anti-semitism, some community-based hate-reporting tools cover a wider breadth of marginalized identities.

Chatham-Kent, a mostly rural community in southwestern Ontario, launched a new hate reporting tool last year through the Chatham-Kent Victim Services’ website.

It collects incidents ranging from verbal abuse to abusive online messages and covers all kinds of discrimination, including discrimination based on age, ability, gender, and race, among others.

This data gives the organization insight into community trends and adds a reporting feature to the non-profit’s victim support services.

The service has an online reporting option and a phone line, said Jason Brown, community engagement coordinator at Chatham-Kent Victim Services. The CK Local Immigration Partnership and the Chatham-Kent municipality helped create the service.

The tool was launched about a year ago, but early data indicates a clear trend.

“Most of the reports we received when we first launched the tool, and ongoing, have involved the queer community,” Brown said.

About 22.3 per cent of reports were targeted at sexual orientation, 21 per cent at gender identity, and 43 per cent involved both.

The high-level data is shared with local organizations and police to help educate and create awareness around this trend, he said

“Being a smaller community sometimes, and in any community, it’s out of sight, out of mind,” he said.

The first step is to recognize what happens and how often it happens, said Brown.

Almost 28 per cent of incidents involved verbal abuse, 13 per cent were acts of violence, 11 per cent were hate-motivated vandalism, and 10 per cent was online hate.

“There’s a lot of work and progress to be made to making our communities more welcoming and more just for all community members,” Brown said.

In Alberta, Chaudhry helped develop StopHateAB, a non-profit that started documenting hate-related incidents across the province eight years ago.

StopHateAB has collected nearly 1,000 reports of hate incidents to date, covering hate symbols and speech, location and timing. Like Chatham-Kent’s service, those reporting are also able to choose whether the incident was motivated by their race, religion, sexual orientation, or disability status – or some combination of factors.

Nina Saini, the executive director of StopHateAB, said the self-identification tool means that the experiences of people holding intersectional identities can be captured, as well as the experiences of those supporting marginalized groups.

“Somebody may be racialized, but may also be advocating for people with disabilities, and that’s why they have been targeted,” she said.

Chaudhry said he and others were working on StopHateAB in 2017 and decided to launch the service just after the Quebec City mosque shooting in 2017 when a gunman killed six people after evening prayers.

The horrific event sparked a new discussion about Islamophobia and how to recognize hate-motivated incidents better and try to track trends.

Community groups recognized the gap in hate data released by Statistics Canada every year and saw a need for something more granular and intersectional, said Chaudhry.

However, years later, he can see the pitfalls many community groups face, including the question of what to do with this valuable data after it has been collected.

What happens with the data?

In the Waterloo Region, the coalition shares its “Snapshot of Hate” report with local governments, school boards and the police.

Chatham-Kent also shares high-level data with police, the local municipality, and groups that serve marginalized communities, Brown said.

These groups said they shared anonymous data with local police services and municipalities to inform them of trends and help shape awareness campaigns or policies to mitigate hate.

But even anonymously sharing data with police is an issue for some marginalized communities.

Chaudhry said someone from an Indigenous community in Alberta reached out to him after StopHateAB launched to commend his work, but he told Chaudhry that his community would not use it.

“They didn’t say it in a negative way. They just said, you know, we have a historical distrust of these types of reporting tools. If there’s any direct or indirect connection points with police we’re probably not going to report.”

The person instead chose to collect incidents of hate in their community and gave Chaudhry 20 pages of people’s stories about racist encounters they have had.

They wanted us to know what their community was facing, so to some degree, it is important to meet people where they are to be able to foster that awareness and to be able to share information about supports they can access, Chaudhry explained.

At arm’s length from police and government – but at a cost

One in five Black and Indigenous people have little or no confidence in police, double the number of those who were neither Indigenous nor a visible minority, according to 2020 Statistics Canada data.

Numerous studies also show that Indigenous and Black people have more interactions with police and more police called on them compared to their white counterparts, pointing to systemic racism in many police services.

Black and Indigenous people are also more likely to be killed by police, accounting for 27 per cent of police-involved shooting deaths despite comprising only 8.7 per cent of the population.

Given the lack of trust between marginalized groups and government entities– which is part of why non-profits began collecting this data in the first place – police could collect this data in partnership with non-profits rather than in opposition to them, Chaudhry said.

According to him, while it’s a good idea for non-profits to collect data, he said many communities work in silos making it difficult to capture national trends.

“There isn’t necessarily even a convening body. I think there’s no obligation, even with how the data is captured, for us to share beyond annual reports.”

The inconsistency in how different groups collect data would make it impossible to pool it together, he said. “It becomes a challenge to even have that data as reliable,” he added.

Chaudhry doesn’t feel any impetus to roll out a national hate-reporting tool that can help capture trends, at least not from the non-profit sector, because of such an endeavour’s sheer scale and cost, he said.

“That’s where I think the community groups are likely going to be pushed out eventually, as more and more government entities start to capture incidents.

“I think the question becomes, where could it be (housed)? Canada Heritage, maybe Public Safety Canada? But I think that’s the million-dollar question for sure.”

Government and police departments, along with Statistics Canada, may not be allowed to use the data community groups collect, said Shafiq, as the data may not adhere to their standards or methodology.

In the absence of a national database, there should be acceptance criteria for community groups to aspire to, said Shafiq.

Most groups collect the data to draw awareness to hate-motivated incidents that communities do not report to police, rather than seeking to build a statistically rigorous dataset.

However, there should be some sort of acceptance criteria for community groups to aspire to, particularly if they are seeking to work in partnership with government entities or police, Shafiq said.

Prioritizing lived experience over quantitative analysis

Project 1907, a grassroots group serving the Asian community in Canada, developed a Racism Incident Reporting Centre, where community members could confidentially report racially motivated hate incidents.

The reporting tool is available in several Asian languages, and findings are aggregated and reported by Project 1907 and the Chinese Canadian National Council Toronto Chapter.

“The tool became a seminal source for news organizations and other groups to use as a market for tracking racist incidents against Asian Canadians during COVID,” said Audrey Wong, executive director of Vancouver-based Elimin8Hate, who collaborated with Project 1907 on the reporting centre.

All the organizations involved are advocacy groups, and Project 1907 is run entirely by volunteers.

In that context, statistical rigour and analysis were not the main goals of the reporting centre.

“It was more effectively used as a qualitative tool to show that there are incidences of hate occurring towards Asian Canadians, which a great group of Canadian society might not be exposed to at all,” Wong said.

She was pleased to hear that in late 2023, the Government of British Columbia announced it would develop a new fund for organizations at risk of hate-motivated incidents.

It was redirecting money seized from organized crime into the fund, and applications were open until the end of March 2024.

The province also announced that it would dedicate $500,000 to a new racism incident helpline, which will sit separately from the police force.

The helpline will be available in multiple languages and refer B.C. residents to community support programs and counselling services. It will also collect and analyze data from the reported incidents and use that to drive funding and resources toward specific interventions.

The B.C. government is working with United Way BC 211 to launch the helpline in the spring, a ministry spokesperson said.

How governments are stepping in

As community groups struggle to secure funding and a clear direction for their data collection, some governments are stepping in with bigger pockets and the ability to fund their tools.

In Edmonton, a city team of data scientists have developed Lighthouse, a set of digital tools that track the proliferation of hate symbols around the city.

Launched last year, Lighthouse uses a phone app to capture images of known and suspected hate symbols, and an online database captures hate symbols by type and affiliation.

The city developed the app in light of a change in its bylaws, which classified hate symbols as hate speech, said Kris Andreychuk, who manages the data science and research team at the City of Edmonton.

Lighthouse helps frontline police officers and law enforcement act on the policy change.

Around 160 police officers are trained to use the tool, Andreychuk said.

The images captured are also analyzed and aggregated into a dashboard and mapped out based on their location in the city.

This data is shared with the Alberta Hate Crimes Unit but isn’t available to the public as the team is concerned that hate groups could exploit the information.

“We’re negotiating a fairly significant expansion of Lighthouse across Alberta,” Andreychuk said. “If this came together, we would see it deployed in Edmonton and six other cities.”

Images are checked manually, but the team also plans to set itself up to integrate artificial intelligence and automation into Lighthouse.

The plan is to present the findings to communities, particularly those affected by the hate symbols, and develop an appropriate response with them around the table, he said

“The longer this runs, the greater our coverage, and therefore, the more statistical rigour there is around that data,” said Ben Grady, a data scientist at the City of Edmonton.

“The longer this is deployed, the more power the data is going to have.”

Support for victims of hate

Organizations that work with victims and marginalized communities know where the gaps are, not only in collecting data and recognizing trends but also in finding ways to heal from traumatic incidents.

But recourse available “is peanuts” compared to the actual impacts people face, said Mohammed Hashim, executive director of the Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

“The way this country is dealing with [hate] right now is not an ideal state, obviously, because for the most [part], hate is left unmitigated.”

Most people who experience hate incidents do not know they can access support and where to find that information, Abid said. Victims need support in navigating these complex systems.

“For a long time, we have advocated for better funding for victim support…We’re trying a lot with a very, very limited budget that we have, like offering free counselling, trauma counselling sessions, offering mediation, offering advocacy,” Abid said of her group’s services for victims of hate.

In Chatham-Kent, Brown said the reporting tool is an additional layer to victim support services the organization already offers.

However, not every third-party service offers direct victim support, primarily because of a lack of funding opportunities.

Funding a constant struggle for third-party reporting tools

The Coalition of Muslim Women’s reporting service is funded by the Region of Waterloo’s Upstream Fund, which aligns with the municipality’s Community Safety and Wellbeing Plan.

For Abid, there are still open questions about continuing that funding – both for the reporting service and ancillary victim support services.

“We have to always think, once this grant is over, what do we do?” Abid said. “Do we dissolve this program?”

“It’s like a constant axe over our heads.”

Funding these reporting services only as pilot programs also makes it challenging to tangibly apply learnings from the pilot stage into a more sustainable, long-term program, she added.

“By the time we have gotten some footing and done outreach, promotions and marketing within the community, it’s time for it to wrap up.

“When do we actually get to build on something? We keep reinventing the wheel each time.”

A “singular sustained source” of information is crucial to keep this work going, and it’s most likely that government bodies will have the structure and funding to continue this work, said Wong.

A significant software cost is attached to collecting this data at scale, added Saini of StopHateAB.

Like the City of Edmonton, StopHateAB aspires to develop a location-based heatmap of where hate incidents are occurring. Saini has also received feedback that the community would like access to victim support services.

“We’d never want to just look at data as data and not be able to support those reporting [hate incidents],” Saini said.

Funding for the reporting tool and these additional services has been hard to come by, she said.

“It’s insane how many funding applications I have written, and I’ll be honest, hate-related work is not an area that seems to be a priority,” she said.

“It’s maybe too scary for corporate funders.”

Saini often encounters pools of funding dedicated to specific marginalized groups. However, because StopHateAB documents hate-motivated incidents across the board, the organization frequently does not qualify for these funding opportunities.

Saini recently received some feedback on a funding application that has stuck with her and made it apparent how challenging it is to collect evidence of hate.

“You guys have a lot of houses, but you don’t have a home,” she was told.