Canadian foundation assets up $100 billion and 5 other findings from a new landscape report

Why It Matters

Data on the philanthropic sector is scarce. A new report aims to help fill the gap with new information on public and private foundations' granting and investments.

It’s been a decade of growth for Canada’s philanthropic foundations, according to a new landscape report.

There are also more assets, more public and private foundations, and more grants.

That’s the word from An Evolving Landscape: Reflecting Canada’s Philanthropic Foundations, co-produced by Philanthropic Foundations Canada, the member association of Canada’s private foundations, and PhiLab, a federally-supported academic hub for philanthropic research.

To simplify your life, we summarized the report’s key findings and asked sector experts to contextualize them.

Foundation assets reach $135 billion in 2021

Since 2008, the total assets held by Canada’s private and public foundations have nearly tripled, increasing by about $100 billion.

In 2008, foundations held about $35 billion. By 2021, that figure swelled to $135 billion.

The explanation for the growth is straightforward math, said Dr. Michele Fugiel Gartner, PFC’s lead researcher.

Financial markets have been strong over the past decade, supporting PFC’s members to earn an average rate of return of about 7 per cent per year on their endowments, according to the report.

During the same period, foundations were required by federal law to spend just 3.5 per cent of assets on charitable programs.

While foundations have to cover some additional costs beyond granting, Fugiel Gartner said those expenses generally haven’t outweighed investment gains.

In addition to this broad trend, one foundation’s asset growth, in particular, has helped to increase the total asset tally.

Between 2008 and 2021, the Mastercard Foundation, Canada’s lone mega-foundation, increased its assets by more than $37 billion—from about $2 billion to $39 billion.

The growth was caused by a dramatic rise in the value of the shares of Mastercard, the American payments giant.

When the company went public in 2006, it issued 10 per cent of its shares to the foundation. As the company’s fortunes have increased, so has the Mastercard Foundation’s charitable wealth.

Growth in private foundations, spurred by tax change

An increase in private foundations has also driven the increase in foundation assets.

Between 2009 and 2021, private foundations increased by about 30 per cent — from about 4,900 to about 6,200.

The increase has been spurred by growing wealth gains among Canada’s most affluent people, Fugiel Gartner said.

Federal tax changes in 2006 also encouraged Canadians to launch new private foundations, according to Hilary Pearson, former PFC president and author of a recent book about Canada’s philanthropic sector.

At that time, the federal government exempted the payment of capital gains on donations of securities, such as stocks and bonds, making these donations less costly.

While many affluent Canadians have chosen donor-advised funds as their philanthropic vehicle, hundreds of others have created new private foundations.

Unlike the United States, where many of the most affluent earn their wealth in large corporations, many of Canada’s most well-to-do are the founders of family businesses, said Pearson.

“[People] who are entrepreneurs are also people who like to start their own foundations. It’s kind of the same way of thinking,” she said.

Educational institutions favourite among foundations

Buoyed by the increase in the number of foundations and their assets, charities have also seen a boost in granting.

Between 2018 and 2021, private foundations increased their grants to charities by 72 per cent and public foundations by 23 per cent, according to the report.

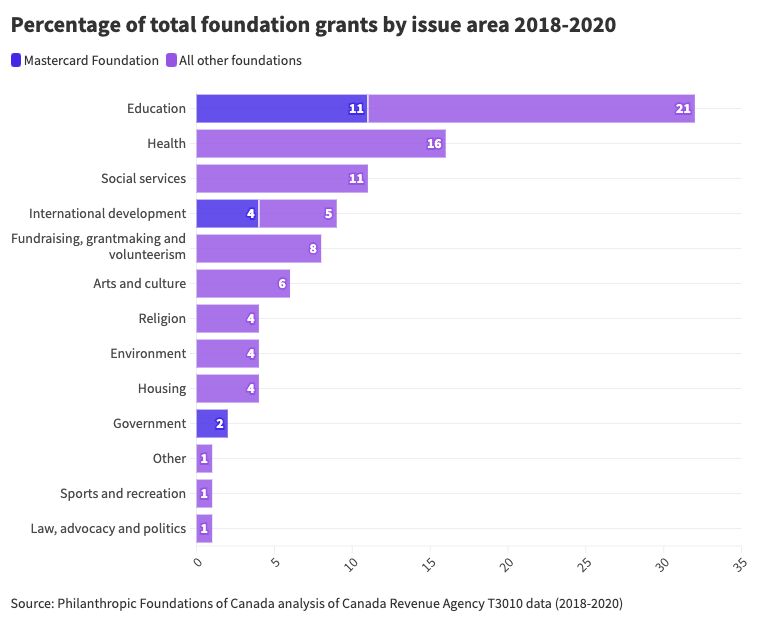

Aligning with long-term trends, educational, healthcare, and social services charities benefitted the most from the increase.

Between 2018 and 2021, Canadian foundations granted 32 per cent of their gifts to educational institutions, 16 per cent to healthcare charities, and 11 per cent to social services charities.

This is no surprise, said Pearson. For as long as researchers have gathered foundation granting data, these three sectors have come out on top—both in Canada and the United States, she said.

However, the finding isn’t bulletproof, she added.

The Canada Revenue Agency data from which the insights are gleaned categorizes granting areas broadly.

A grant to a university to fund environmental research would be categorized as supporting education, not the environment, said Pearson.

This may account for why areas of increasing importance, such as the environment or housing, appear to be garnering relatively modest attention, she added.

Between 2018 and 2021, environmental and housing-focused charities netted just 4 per cent of foundation grants.

Traditional investing remains dominant among PFC members

According to the report, foundations, despite the uptick in grants, demonstrated more modest progress on socially responsible investing.

A 2021 survey of PFC members found that among 66 respondents, less than 40 per cent had adopted any sort of social investment strategy, including negative screens (where a foundation screens out investments in industries perceived as harmful), socially responsible investments or impact investments.

Among PFC members, the number of foundations that have reported having any impact investments has been in the teens from 2015 to 2021, according to the report.

Adam Jagelewski, managing partner of impact investment firm TwinRiver Capital, said foundations face several barriers in adopting socially responsible investment strategies.

Most Canadian foundations are small and do not have their own investment policies—a document that outlines what the foundation will or will not invest in.

Without it, foundations’ investments are largely dictated by the selections made by their external investment managers—staff whose positions are often long-term or legacy appointments connected to a family’s corporate or family office, according to the report.

Pursuing socially responsible investing thus requires the foundation’s volunteer directors to invest time and energy to convince these professionals to change their approach, he said.

In addition to this barrier, some foundations have also been stymied by a lack of available impact investment products, he added.

Like other sectors of the economy, investment providers are trying to catch up to consumers’ increasing interest in sustainability, but it takes time, Jagelewski said.

As mainstream providers struggle to adapt, new market entrants like TwinRiver Capital and other impact investment-focused firms aim to fill the gap.

Though the uptake has been modest, Pearson said foundations’ moves toward socially responsible investment have nonetheless been significant.

Two decades ago, few foundations discussed socially responsible investing. That’s changed over the past several years, she said.

Some foundations, including the McConnell Foundation, have also invested heavily in impact investments over the last several years.

By 2022, more than 20 per cent of the foundation’s $650 million in assets were invested in impact investments, and the foundation is aiming for 100 per cent “mission-aligned” investments by 2028.

“It could be faster. It could be more urgent, for sure. But I do see over the last two decades, [the change is] really significant,” said Pearson.

Lack of investment in staff remains a challenge: Pearson

Across foundations of all sizes, few invest in staff, according to the report.

In 2020, 74 per cent of public and 91 per cent of private foundations were volunteer-run.

Among foundations that do have staff, large teams are also rare. Only 4 per cent of foundations of either type reported employing more than 50 people in 2020.

These figures can be partially explained by the fact the average size of a Canadian foundation is relatively small, said Pearson.

In 2021, about 10 per cent of all foundations had more than $10 million in assets, according to Canada Revenue Agency data.

However, according to the report, even among large foundations, some choose not to invest in paid employees.

The reason why hasn’t been studied in Canada, but UK research suggests some foundations are reluctant to invest in staff because they want to focus on high family involvement in the institution.

For others, it’s because of an orientation toward low overhead costs or based on a lack of understanding about the labour required for good grantmaking, Fugiel Gartner said.

Sector at a ‘high point’ for research?

The academic terrain for the year-long project that led to this report was fertile, said Fugiel Gartner.

For the past several years, academics associated with PhiLab have been producing reports on various topics—from Indigenous philanthropy to the impact of operational funding, leading to a “high point” in knowledge about the sector, she said.

Still, she said, much remains unknown about philanthropy in Canada, and the research process identified how much more there is to be explored.

Moreover, progress may also be at risk.

PhiLab is nearing the end of its federal funding, and Canada is the only G7 country without a research facility dedicated to philanthropy.

To turn the tide, Carleton University, the site of a prominent philanthropy and non-profit Master’s program, seeks to become the first such institution nationwide.

Pearson hopes foundations, which have historically under-invested in research about the sector, will see the value in supporting the initiative.

“This is not just for selfish reasons,” she said.

“We need to have a solid research capacity in this sector so good policy can be made, so people can understand better what foundations are doing and why they do it, and for foundations themselves to learn and be better at what they do.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated Dr. Michele Fugiel Gartner’s title. Future of Good regrets the error.