Charities unite against Alternative Minimum Tax changes — but at what long-term cost?

Why It Matters

Trust in charities is declining. Some worry a recent campaign could threaten it further, leading to lower donations in the long run.

Why are charities fighting against a proposed law that would see rich Canadians pay more tax? This is the second of a three-part series exploring the sector’s advocacy against the Alternative Minimum Tax. Read the first story here.

The charitable sector’s support of a tax policy change that benefits wealthy Canadians may offer short-term relief but induce long-term headaches, say two experts and a foundation CEO.

“The short-term issue is how to protect the charitable sector. The long-term issue is how to protect the philanthropic sector’s reputation,” said Karel Mayrand, CEO of the Foundation of Greater Montreal.

The conflict stems from the policy position taken by the country’s largest charitable sector associations and many of Canada’s largest charities in response to a federal tax proposal.

In Budget 2023, the government proposed reducing two donation incentives for high-income Canadians as part of broader changes to the Alternative Minimum Tax regime to increase tax fairness.

But fearing a significant decline in donations, the charitable sector mobilized.

In September, Imagine Canada, the country’s largest charitable association, supported a delegation to lobby members of parliament to scrap the proposed changes and facilitated 1,200 organizations to write to the Department of Finance urging the government to re-think the plan.

The Canadian Association of Gift Planners, a charitable association of fundraisers, financial advisors and lawyers, also rallied 180 organizations to co-sign an open letter, encouraging a policy re-think.

In letters to the government, Community Foundations of Canada and United Way Centraide Canada also urged removing the donation-related changes from the AMT update.

The CEO of Philanthropic Foundations Canada, the association of private and family foundations, spoke about the policy change during a speech at the sustainable finance forum in Ottawa in November, warning about a potential negative impact on donations.

“Charities should not suffer collateral damage from legitimate efforts to ensure the richest among us pay their fair share of taxes,” he said.

While Mayrand said the sector’s advocacy was warranted given the challenging financial position facing many charities, he added it comes at a cost.

“The house is on fire, so these associations are trying to put the fire out. But the way to put the fire out is to maintain the privilege [of a few] and a fiscal regime that is not necessarily fair,” he said.

A threat to philanthropy’s legitimacy?

Mayrand’s concern is the reputational risk charities face if they fight to protect a federal donation tax credit system that he said disproportionately benefits the wealthy.

Under Canada’s current gift incentive regime — among the world’s most generous, Canadians pay no capital gains on stock donations and gifts of several other types of securities.

This results in far greater public subsidies for the donations of higher-income Canadians who hold more of their wealth in assets that accumulate capital gains.

In 2015, Canadians with taxable incomes of more than $250,000 accounted for 84 per cent of the total amount of capital gains exempted from taxation on donations of securities, amounting to over $300 million exempt from taxation, according to a Department of Finance report.

Canadians with less than $100,000 in taxable income in 2015 accounted for six per cent of the total exemption, amounting to $20 million in capital gains exempt from taxation.

Under the current Charitable Donations Tax Credit rules, Canadians in the highest income tax bracket also get more tax relief than their lower-income peers for donations of the same size.

In 2023, a Canadian earning more than about $235,000 — enough to be in Canada’s top income tax bracket — would receive $28 more in federal tax relief on a $1,000 cash donation than a peer making the same size gift whose income places them outside the top income tax bracket.

Canada’s donation incentive system also offers non-refundable tax credits rather than rebates, which means low-income people who pay no income tax cover the total cost of their donations – receiving no public subsidy for their philanthropy.

Malcolm Burrows, head of the Aqueduct Foundation, one of Canada’s largest donor advised fund foundations, said wealthier Canadians get more donation tax credits because they pay more tax.

“The system is trying to make sure that there’s an acknowledgement or an offset, so you’re not paying a public contribution twice,” he said.

But Mayrand doesn’t view it that way, believing the donation tax credit system is disproportionately advantageous to wealthy Canadians.

“It’s way more difficult for someone to give $1,000 than for someone to give $1 million. So, why is it that the government is supporting $1 million more than $1,000?” he said.

Additionally, Mayrand said he fears there may be a long-term financial cost to charities in advocating to preserve the status quo.

Decline in trust

Over the last 20 years, trust in Charities has plunged.

Between 2003 and 2013, 70 to 80 per cent of Canadians trusted charities, according to a summary of polling data analyzed by consultant Steven Ayer. In polls conducted over the last several years, that figure is closer to 50 per cent.

Mayrand said he fears the charitable sector’s advocacy to preserve unequal philanthropic tax credits could further undermine faith in the sector.

As evidence of growing awareness of this issue, he pointed to a January article in the French-language daily tabloid, the Journal de Montreal, highlighting how very wealthy Canadians can reduce the cost of donating to nearly nil through an obscure tax credit program.

Numerous recently published books, such as The Bill Gates Problem and For-Profit Philanthropy, have also focused on the benefits elites receive from their philanthropic endeavours.

The big concern is growing mistrust will lead fewer average Canadians to donate — a trend that has been increasing for several years, he said.

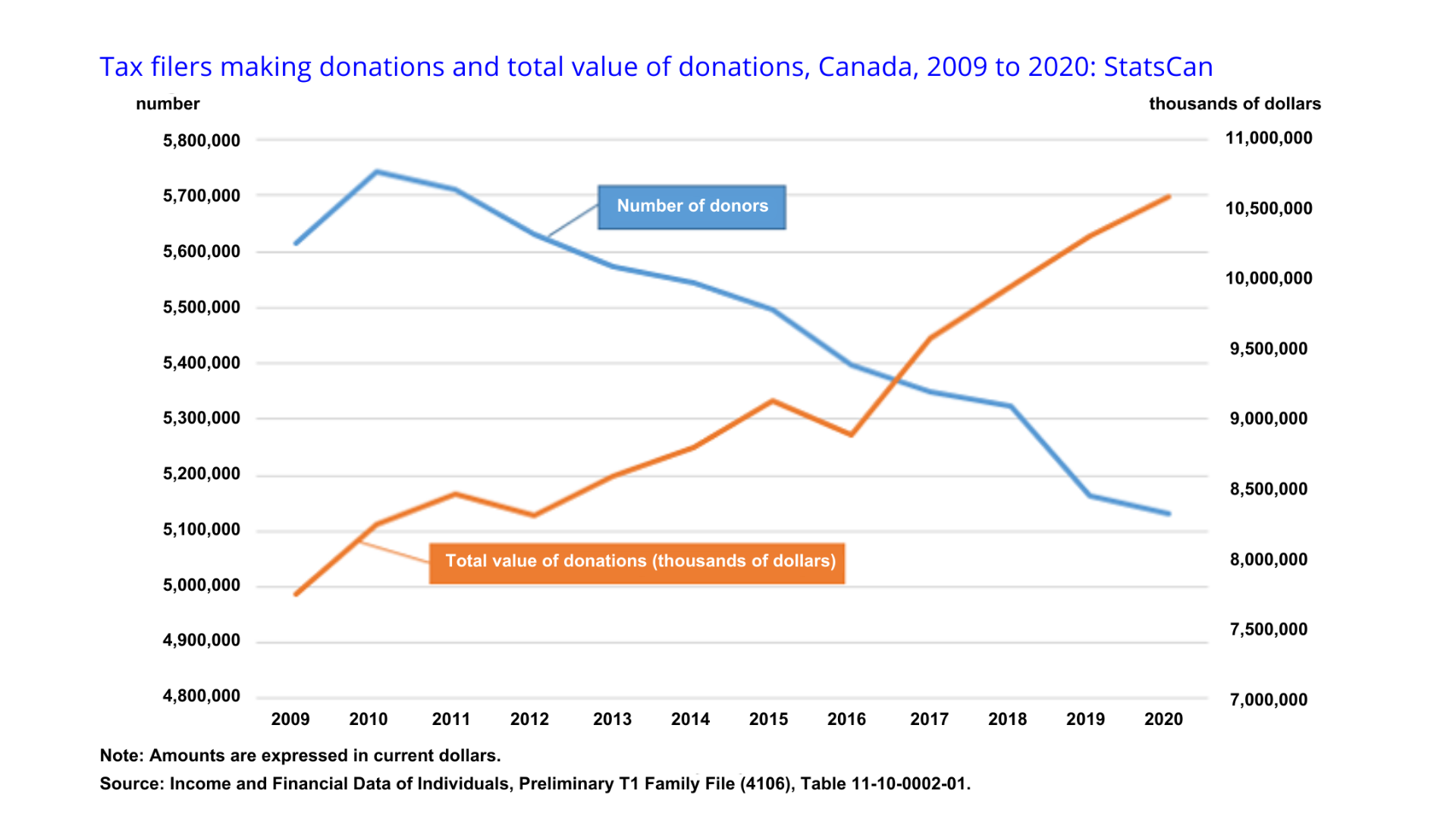

In 2021, the number of Canadians claiming a charitable donation tax credit declined for the eleventh year in a row, dropping from a high of nearly six million donors in 2005 to fewer than five million in 2021, according to Statistics Canada.

Yet despite the overall drop in the number of donors, the total amount of donations increased to a record high of $11.8 billion, up 23 per cent from 2017, buoyed by large gifts from affluent donors.

At a certain point, charities need to question the fiscal regime making them increasingly reliant on gifts from high net-worth donors, Mayrand said.

Instead of focusing on “defensive battles” like the AMT, he added that charities should be fighting to expand the donation incentives for average Canadians and make clear that philanthropy is not only for the wealthy.

Thomas Malleson, an associate professor at King’s University College in London, Ont. who studies inequality and taxation, agreed with the need to make the tax system more fair.

“Charities often do good work, but that good work is completely reliant on them being able to get donations from the rich,” they said. “That is not a democratic way to arrange society.”

“The democratic way to arrange society is we tax ourselves, including the rich, and pay for the goods we want,” they said.

CAGP’s position on AMT focused on giving

Ruth MacKenzie, CEO of CAGP, agreed with Mayrand’s concerns about trust and a declining donor base. But those concerns were not the focus of her organization’s AMT position, she said.

“We didn’t have philosophical conversations about a more just and equitable future for philanthropy in Canada. This is a technical tax policy proposal,” focused on the impact of the AMT to charitable donations, she said, of her organization’s submission to the government.

The C.D. Howe Institute, a Canadian think tank, has estimated the donation-related AMT changes would result in a four per cent decrease in donations sector-wide.

In 2021, this would have amounted to $500 million less for Canadian charities, according to the report.

But Olivier Jacques, an assistant professor at the University of Montreal who studies inequality, said tax policy is inherently social policy and that there can be no distinction between the two.

Jacques was stunned to learn that United Way Centraide Canada, a charity focused on poverty reduction, signed CAGP’s open letter advocating for the status quo in donation incentives.

This means United Way believes it does a better job of solving poverty than the government, he said. “This is awful. This is really awful.

“I’m actually thinking about stopping my donations to them right now,” said Jacques, a longtime donor to the Centraide of Greater Montreal.

AMT changes projected to net $2.6B over five years

The proposed AMT changes could also increase long-run strain on the social sector by stressing the government’s capacity to raise sufficient revenue to fund necessary social programs and services, said Malleson.

“In the short term, of course, I want the charities to keep their lights on because they’re providing, in many cases, useful services for poor and marginalized people,” they said, empathizing with CAGP’s position.

“But in the medium and long term, in any decent society, I don’t want there to be poor and marginalized people….In any good society, we wouldn’t need those charities.”

The Parliamentary Budget Officer projects the package of AMT changes would net $2.6 billion over five years.

These funds could be used to support the government’s investments in social services, reducing the gaps necessary for charities to fill, said Katrina Miller, executive director of the advocacy group Canadians for Tax Fairness, in an August interview

“[Charities] become burdened with social responsibilities when the government decides to exit itself from public programming when it doesn’t have money,” she said.

However, not all believe decreasing donation tax credits is the right way to raise public revenue, nor that it promotes more fairness in the tax system.

The AMT changes will mean higher-income donors now have less of a tax incentive to give than their lower-income peers, said Tina Thomas, CEO of the Edmonton Community Foundation.

The proposed changes reduce the donation tax credit from 100 to 50 per cent and reduce the capital gains exemption from 100 to 70 per cent for Canadians with taxable incomes of over $173,000 who calculate their taxes using the AMT method.

At a time of pressing social need, she said we should not be putting up roadblocks to discourage affluent Canadians from giving based on a feeling they have too much money.

“We want the government to do their part, but we [also] want individuals to do their part.”

Government delays AMT changes

In December, the government did not pass the AMT changes as had been proposed in the 2023 Budget.

Mayrand said he is hopeful the government will move forward with the changes but bring them in over a few years, minimizing the potential for a “fiscal shock” to the charitable sector.

Alongside, he wants the sector to talk about tax.

“Everyone in the Western world is being exposed to public scrutiny more and more than in the past, so you have to pass the test of trust,” he said.

“We should not wait for more articles to come out in the papers about how unfair philanthropy is.”