The Conservatives mention civil society more in their platform than any other party. Why?

Why It Matters

The Conservatives are neck-and-neck with the Liberals in preliminary election polling. How they think about the sector, should they win, could determine the likelihood of partnerships with the government and funding opportunities for civil society organizations.

“Bleeding heart liberal” is a persistent stereotype of social impact professionals across the sector. Socially aware, politically empathetic, ready to put aside well-paying work in business for the good of their communities or a social cause. Yet Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole’s election platform mentions civil society more than any other major party running in the 2021 federal election.

When it comes to the importance of Canada’s civil society, modern conservatism, modern liberalism, and modern progressivism are largely on the same page. All three strands of political thought believe communities should be able to improve and control their own lives outside of government intervention, although there are some crucial differences. Progressives tend to favour public service delivery, while classic liberals (and more moderate conservatives) believe in free market economics while championing equality. Still, there’s plenty of common ground.

“There’s a lot of emphasis on decentralizing, localizing decision-making, putting resources into people’s hands to make their own decisions about it, and not having governments heavy-handedly tell people what to do,” said Lisa Sundstrom, an associate professor in UBC’s department of political science.

This theme especially appeals to “small-c conservatives” who favour smaller government. But the rhetorical similarities largely end there.

Conservatism believes non-profits and charities can augment social services provided by governments — and could replace them entirely. It also prioritizes different civil society causes than progressivism and liberalism, especially around foreign policy. And Canadian conservatives tend to view political advocacy by civil society to be a no-no — a contrast to other political skeins where organizations that work with communities on pressing social issues should be allowed to openly pressure governments to do the right thing.

Future of Good reached out to thirteen Conservative Party candidates running in the election to get their perspective on conservatism and civil society. All of them declined to be interviewed or did not respond. Still, experts and the Conservatives’ own platform helped illustrate how the party typically talks about civil society, what it is promising should it win on Sept. 20 — and whether conservative governments actually treat the social impact sector differently in Canada than their ideological counterparts.

Small government = big sector

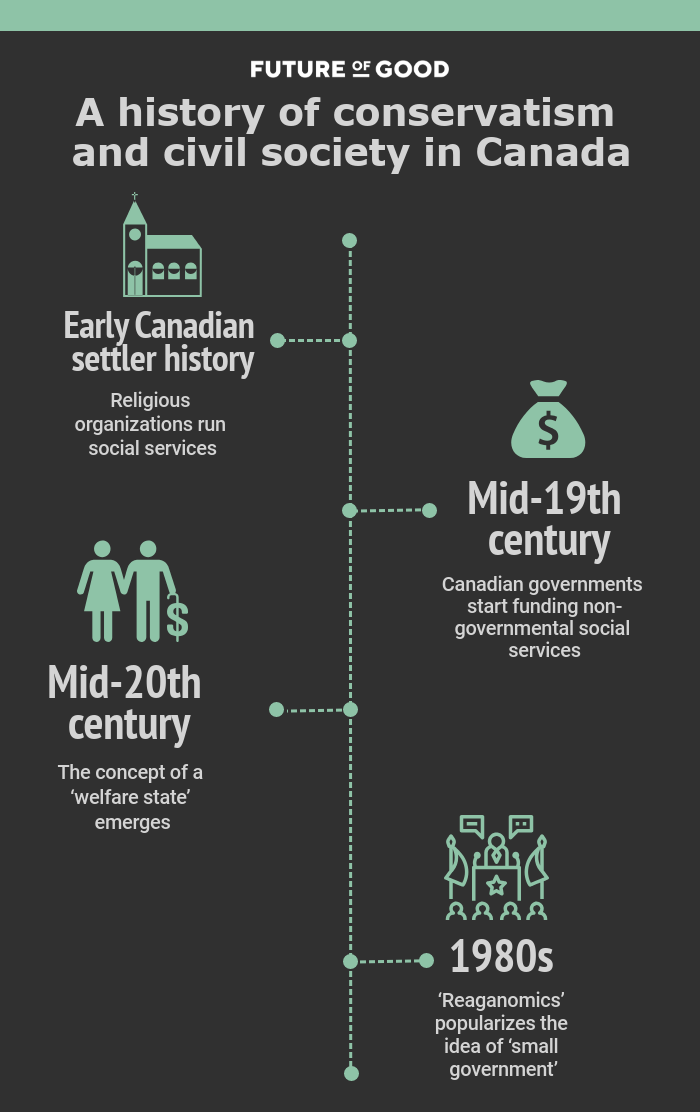

For much of Canada’s settler history, the state — either Britain, France, or Canada’s own government — was not responsible for providing social services. Religious organizations like the Catholic and Anglican churches ran hospitals, almshouses (effectively food banks) and shelters. Canadian governments didn’t start providing funding for charities in an organized fashion until the mid-19th century. It wasn’t until the 1850s and 1870s that civil society organizations such as the YMCA and YWCA sprang up in Canada. Only in the mid-20th century did the concept of the ‘welfare state’, a government that actually provided social services like employment insurance and guaranteed old age pensions, arrive on Canadian shores.

Conservatism looks back fondly at this idea of relying on civil society organizations for social services, instead of relying on universal government-funded programs. This is especially true after the arrival of former U.S. president Ronald Reagan’s strain of conservatism in the 1980s — sometimes called ‘Reaganomics’ — that championed smaller government expenditures above all else. “Civil society in a conservative lens becomes a vehicle for dismantling government, or at least reducing the scope of government,” says Barry Eidlin, assistant professor of sociology at McGill University.

But Eidlin says conservatives are also concerned about ‘social order’, the (theoretical) idea of a harmonious and functional society where politicians and ordinary citizens alike are well off, but live within a structured hierarchy. “Civic institutions are a framework of maintaining social order, ” he explains. Balancing the desire for small government and social order requires an institution to pick up the slack in social services — and civil society is often seen as the ideal way to achieve that equilibrium. It doesn’t always require government funding, yet still sees social services as critical to a community’s health and resilience.

O’Toole’s platform does not explicitly talk about dismantling public services in favour of civil society. However, his platform does lean on the social impact sector as a way to fund Canada’s recovery from COVID-19. “To boost charitable donations, Canada’s Conservatives will also increase the disbursement quota for charitable foundations to 7.5 [percent] to unlock billions of dollars built up tax-free in foundations and put this money to work to help Canadians,” it reads.

Conservative civil society priorities

The other way conservatism differs from liberalism and progressivism is in what social causes should be funded through civil society. Abortion rights groups typically don’t get a lot of attention from conservative parties, Sundstrom says, but liberal and feminist sides of the political spectrum definitely do. (To be clear, O’Toole’s platform does not say anything about refusing to fund abortion rights groups. It simply says the Conservatives, if elected, would not re-open the abortion debate in Canada).

All but two mentions of the word ‘civil society’ in O’Toole’s platform refer to building the sector’s capacity abroad, in countries like Russia and Belarus, as well as the Middle East region as a whole. “This idea of civil society is tied up with notions of Western democracy — that civil society is a necessary component of democratic institutions,” explains Micheal Shier, associate professor in the University of Toronto’s faculty of social work. This viewpoint isn’t unique to conservatism, but Sundstrom says right-leaning parties are especially keen on promoting civil society abroad. “The Conservatives really want to protect and defend democracy and the idea of individual liberties strongly in those places, so they’re willing to put money into it,” she says.

Another priority for the Conservative platform is moving refugee resettlement away from the government and into the hands of private and non-profit partnerships. “Privately sponsored refugees receive critical social and cultural support which allows them to adapt to a new environment and learn how to succeed in a new economy,” the platform reads. “Ideological Liberals persist, nonetheless, in limiting private sponsorship at the expense of less effective government refugee sponsorship.” And the Conservatives also vow to work with LGBTQ organizations in Canada to facilitate more participation in refugee sponsorships from countries like Iran, where LGBTQ residents can face execution.

Meanwhile, O’Toole’s platform doesn’t emphasize the role non-profits and civil society could play in childcare, nor does it provide funding boosts for organizations working in these areas. “There’s no commitment to creating more spaces, but certainly to help people get tax credits for childcare, ” says Dixon Sookraj, an associate professor at UBC’s School of Social Work. Both the NDP and Liberals are promising to work with non-profits on childcare and affordable housing to varying degrees.

The role of political advocacy by civil society, however, is something Canada’s past conservative governments have tried to limit. Under former Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper, non-profits and charities who worked on environmental, human rights, and Indigenous rights issues — many of which the federal government did not support — complained of repeated auditing by the Canada Revenue Agency. By contrast, liberal and progressive visions of civil society tend to see it as a sector that should be capable of challenging power, although, as always with broad political ideologies, there are exceptions.

There is nothing in O’Toole’s platform about cracking down on charities who speak out, but Canadian law already restricts what is considered ‘political speech’ by registered charities. “There is a price to pay to be a charitable organization — and the price is your silence,” Sookraj says.

Meet the new boss

Despite these differences in thinking about civil society and social impact, Shier says the approach conservatives take to actually working with the sector is remarkably similar to progressives and liberals. He says there isn’t any evidence to support the idea that conservatives, liberals, and social democrats think about the sector in different ways.

“Governments in Canada have tended to treat the sector in a very contractual way,” Shier says, “and also in a way that helps to actually maintain the power of government over civil society.”

Take the rhetoric used by governments around social services. Shier says they often speak of “social investments’ ‘, while a conservative government might lean on the idea of smaller government and empowering citizens to become self-reliant. “It’s the exact same thing,” Shier says. “They’re engaging with the sector by highlighting its role, but it leads to the exact same outcome. It leads to cuts in funding to non-profits.”