CRA guidance on non-qualified donees a ‘good first draft’ but leaders are pushing for several big changes before government finalizes policy

Why It Matters

For more than a decade, non-profits and grassroots groups have been stymied by CRA policy that has prevented them from getting grants from foundations. After a sustained advocacy campaign, that’s on the cusp of changing.

Peace Tower in Ottawa, ON (Photo: Pixbay)

This independent journalism is made possible by the Future of Good editorial fellowship covering the social impact world’s rapidly changing funding models, supported by Future of Good, Community Foundations of Canada, and United Way Centraide Canada. See our editorial ethics and standards here.

Non-profits and grassroots groups may soon find it a heck of a lot easier to access funding from foundations and charities.

In June, following a sustained advocacy campaign, the federal government made a change to charity law that opened the door for foundations and charities to grant to non-profits and grassroots groups.

Charity advocates celebrated that move, but have kept a watchful eye on the Canada Revenue Agency (the agency that regulates registered charities), keenly awaiting the publishing of the agency’s draft “guidance” document on the topic, which outlines in more precise detail than the law, how the regulator will expect charities to grant to their non-charity peers.

In late November 2022, the document was published, with a request from the regulator for the public to provide their feedback on the document by January 31.

In advance of that deadline, Future of Good spoke with more than a dozen non-profit, foundation, grassroots and charity sector leaders for their reactions to the document.

Jean-Marc Mangin, president of Philanthropic Foundations Canada called the guidance document a “good first draft” — a perspective echoed by many of his peers, who said they largely felt the guidance would encourage more grantmakers to work with non-qualified donees.

“I really applaud the CRA,” says Janet Fitzsimmons, a sector consultant, who has worked with grassroots groups and charities for 20 years. “It’s hard to move the machinery at all. And they’ve done that. And I think that’s a good step.”

Speaking in French, Jacques Bordeleau, co-coordinator of Le Collectif Des Fondations, an association of Quebec-based foundations, says the draft guidance and policy change is “one of the most interesting things the federal government has done in a long time,” and that it creates the conditions for a significant change in the power relationships between foundations and grantees.

In particular, professionals were pleased to see the CRA clearly state that granting relationships between charities and non-charities needn’t be hierarchical — that a grantee can maintain their own autonomy and that the grantor does not need to provide ongoing instructions to a grantee about how to use grant funds.

While these provisions may seem logical, they represent a significant break from the “direction and control” regime in place for more than a decade. Many sector professionals said the former regime led to “colonial” and “paternalistic” relationships, undermining important work across the country.

Alongside their celebration of the draft guidance, however, professionals who spoke with Future of Good also raised several concerns, namely: the hefty focus on risk, the length of the document and the approach recommended for how charities should assess risk.

In addition, sector professionals who spoke with Future of Good were mixed in their feedback on an additional recommendation in the document — that funders require grantees to track funds from each grantor separately in order to be able to account for the precise location of each dollar spent.

Beyond the specific recommendations, sector leaders urged other non-profits to engage in the consultation process, by reading the document and submitting their feedback by the January 31 deadline.

“It feels like a once in a lifetime opportunity to fix this,” says Jehad Aliweiwi, executive director of the Laidlaw Foundation, of the challenges associated with the direction and control regime.

Draft guidance document mentions “risk” 62 times

Working with non-qualified donees is not inherently more “risky” than working with charities. That’s the message sector professionals who spoke with Future of Good say they want the federal charity regulator to understand and reflect in the final version of the guidance document.

Mangin notes the draft document uses the word “risk” 62 times, contributing to a perception of non-qualified donees as less trustworthy organizations. By contrast, he says, the key risk any grantmaker should consider when disbursing funds is whether a gift falls within their charitable purpose. Beyond that, he says, the risks of granting to charities and non-charities are one in the same.

Fitzsimmons agrees, adding that it’s important to be specific about what risks the government is trying to guard against when making public policy. She says the document clearly implies grantmakers should be wary of additional financial risks when granting to grassroots groups. Fitzsimmons says, however, in her experience, grassroots groups are just as fiscally prudent as their charity peers.

She adds that the focus on financial risk also distracts from another, perhaps more important risk policymakers should be considering when drafting the guidance: the risk to people and communities that stems from the continual under-resourcing of grassroots groups.

Fitzsimmons says many grassroots leaders are best positioned to solve the challenges they and their communities face, but have experienced financial scarcity for many years.

“What scarcity, long-term, does is it erodes people’s ability to imagine and it erodes people’s ability to hope.” she says. “That’s the cost. The cost is that good people with skills and talents and solutions and the will to want to help, lose that…The cost is that people stop being able to imagine anything different.”

Aliweiwi agrees, adding the document’s focus on risk and accountability is indicative of a broader challenge: that charity policy is being crafted by a tax enforcement authority.

“I think there is something fundamentally problematic about that,” he says, “that the entire charity regime is being managed by an enforcement agent.”

Over several years, many charity advocates have called for a “home in government” for the charitable sector — a ministry that would focus on policy that can support the sector.

Aliweiwi acknowledges this desired change is beyond the scope of this consultation, but says the document’s focus on risk is indicative of challenges that arise when an agency with the task of enforcing the Income Tax Act is responsible for crafting key policy that will define relations between tens of thousands of charitable organizations across the country.

Janet Fitzsimmons, a charitable sector consultant, says she “applauds” CRA on the first draft of their guidance document to support charities in making grants to non-qualified donees, but worries about the document’s significant focus on “financial risk.” (Photo courtesy of Janet Fitzsimmons)

Document length may scare some grantmakers off

Beyond the focus on risk, some sector professionals worry the sheer length of the document may mean some grantmakers don’t bother learning about their new abilities to grant to non-qualified donees.

“I think one of the concerns is that the document is so big that [organizations might] not try new things, because they’re overwhelmed,” says Bruce MacDonald, CEO of charity advocacy association, Imagine Canada.

MacDonald says the document length and detail could also prevent non-qualified donees from taking the time to learn about how they can newly access funds from grantmakers.

Anecdotally, Future of Good’s own experience in trying to interview non-qualified donees for this story suggests this may be true. Though we contacted many non-profits and grassroots organizations for this story, just a handful agreed to speak with us — a much lower rate of response than for source requests for other stories.

Among those who responded, but declined to be interviewed, several cited a lack of capacity to read and interpret the document in order to offer comment. Of those who were willing to speak with us, several directed us to lawyers or accountants within their organization, suggesting, perhaps, that the document isn’t an easy read for all.

Nancy Wilson, executive director Canadian Women’s Chamber of Commerce, a non-profit organization (and an accountant by training), says she appreciates the detail of the document, but suggests CRA create a one or two page summary for lay people and a more detailed version of the recommendations for the accountants and financially savvy folks who want to read the details.

Mangin agrees: “The basic tool should be as simple as possible.”

He says the core document should state a few essential things — that gifts to non-qualified donees still need to fall within a grantmakers charitable purpose, for instance, and that funders engage in some up-front and ongoing accountability practices — but beyond that, he says, many of the detailed examples and tables found in the draft document could be put in an annex.

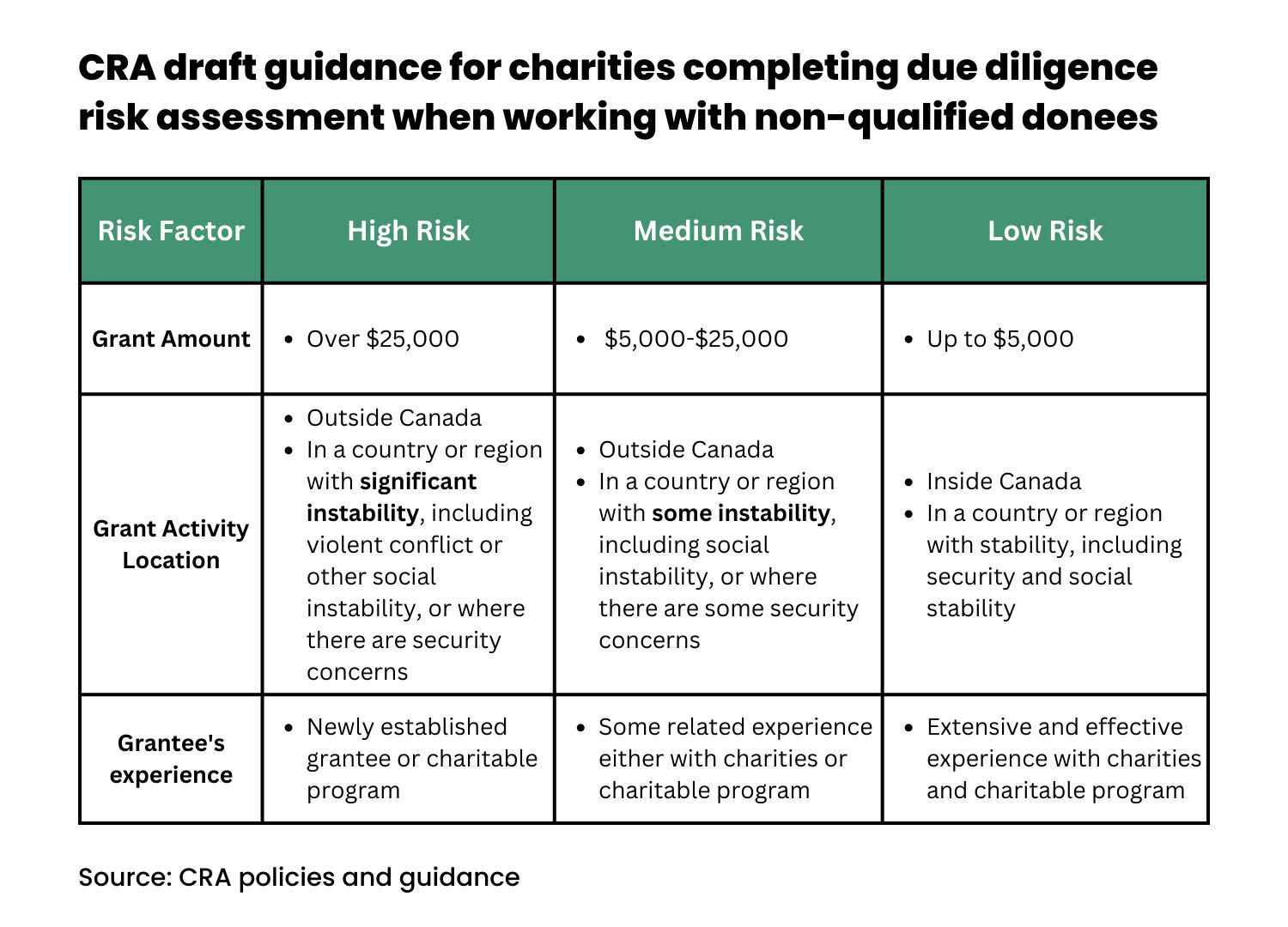

CRA’s draft guidance recommends a $25,000 grant be considered “high risk” when a grantmaker is working with a non-qualified donee. (Graphic: Gabe Oatley)

$25k grants should not be considered “high risk”

Sector professionals who spoke with Future of Good also took issue with one of the tools the CRA recommends charities and foundations use in order to “minimize risk” and to meet the agency’s requirements, suggesting it may need a re-work.

The tool is a chart the CRA recommends grantmakers use at the beginning of a donation process, when assessing the risk of working with a non-qualified donee partner. It includes several “risk factors,” such as a grantee’s experience, the size of the grant being offered, and the location where the grant activity will take place.

The tool says a donation of over $25,000 should be considered “high risk,” as should a donation to an organization whose work will occur in a country or region with “significant instability,” such as violent conflict or a lack of access to financial institutions.

Several professionals we spoke with, however, said these areas may need to be scrapped or revised.

“$25,000 doesn’t really go that far,” says Cherie Payne, director of government relations for The Vantage Point, a Vancouver-based non-profit support organization. “It wouldn’t cover a salary for one person. There’s only so many supplies you could buy with $25,000.”

She says calling that threshold “high risk” is “arbitrary” and not well aligned with dollar values of the grants many non-profits receive across the province.

Aliweiwi agrees the threshold is too low: “We know that for any meaningful change or momentum-creating grant, you really have to have a larger amount for a longer period of time.”

As for what to raise it to? Wilson, who agrees $25,000 is too low, says it might be better to get rid of the numbers altogether, suggesting it’s hard to compare the risk profile of grants in a numerical way across so many distinct sectors.

“If you’re talking about providing funds for disaster relief, $5,000 is never going to be on the table — you’re talking about tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not more,” she says. “But if you’re providing a grant for a business owner to do initial start-up funding for their business, $5,000 might be an upper or medium-limit.”

Could assessing a country’s ‘stability’ discourage making important grants?

Beyond the dollar amount, two sector professionals, too, felt the focus on country instability should be changed or eliminated, suggesting it’s not possible to objectively categorize country stability.

Mangin, who worked in the global development field for many years, says “contextual understanding is key.” He says it’s possible to do work in a country that “on paper” looks relatively stable, but is in fact very high risk from a safety standpoint, giving the example of a human rights-related grant in a politically stable country with repressive laws. By contrast, he says, it’s also possible to work on a “low risk” health project in a country that’s in the midst of war, because local stakeholders may have made a firm commitment to not interfere with the grant’s programming.

Désirée Nore Duchesne, co-founder of TRAPS, a grassroots, transfeminist collective in Montreal, agrees with Mangin. She says trying to categorize other countries by risk is not the right approach — both because it’s not possible, and because it might actually lead to making granting decisions that limit Canadians’ support of communities facing the greatest challenges.

“At the end of the day, is that what we want to really think of when it comes to helping a community that is extremely marginalized?…Like, ‘Oh, there’s too much risk. We shouldn’t give them money?’” she asks.

Désirée Nore Duchesne, co-founder of TRAPS, a grassroots, transfeminist collective in Montreal, says categorizing countries by “risk” isn’t the right approach. (Photo: Samuel Miriello)

Désirée Nore Duchesne, co-founder of TRAPS, a grassroots, transfeminist collective in Montreal, says categorizing countries by “risk” isn’t the right approach. (Photo: Samuel Miriello)

Mixed reactions around ‘separately tracked funds’

While there was consensus around much of the feedback offered by sector professionals we spoke with, one aspect of the document solicited a diversity of perspectives: whether it’s a good idea for the CRA to recommend grantors require grantees to separately track spending associated with donations from different funds.

Separate tracking means that a grantee who receives funds from eight different grantors should be able to report back on where each funder’s dollars were spent — be it $2,034 for honoraria from Funder A and $75 for workshop supplies from Funder B.

For Mangin, this approach is reasonable. “I think separate ledgers — that’s fair,” he says.

Cathy Taylor, executive director of non-profit advocacy network, Ontario Nonprofit Network, also thinks this recommendation is reasonable. She clarifies that the CRA isn’t suggesting grantee organizations need to have separate bank accounts to track funds from each grantor, but rather simply suggesting organizations keep tabs on the source of their funds for each expense, via an organization’s accounting software or on an Excel spreadsheet. “That’s not too onerous,” she says.

Duchesne disagrees, however. While she agrees with Mangin and Taylor that accountability around funding is important, she says such detailed tracking is time-intensive and is often not valuable for the grassroots organizations themselves.

She adds that many organizations do not have anyone on their team with accounting expertise, creating an additional barrier: “Unless you have someone who has been involved in finance, I don’t know if it’s realistic,” she says.

Jane Rabinowicz, chief program officer for the McConnell Foundation, agrees with Duchesne that separate fund tracking is onerous for grassroots groups. She notes that in 2021, 23 per cent of the foundation’s funds went to non-qualified donees — and the private foundation does not regularly require organizations to separately track funds.

“Checks and balances are important. Due diligence is important. Managing risk is important,” she says. “[But] there are robust ways of assuring appropriate financial management and governance and preventing fraud that don’t necessarily require a separate bank account or separate tracking of funds.”

She says as part of the foundation’s grant application process, they ask for project budgets as well as review an organization’s leadership and governance processes — alternative approaches to ensuring the organization is doing its due diligence.

Consultation closes in three weeks: groups encouraged to engage

Several sector professionals who spoke with Future of Good say they’re hopeful that the final CRA guidance will create the conditions for more money to flow from grantmakers to non-qualified donees, but urged other non-qualified donees to read the draft guidance and make their voice heard.

“This is one of the biggest changes we’ve seen to the rules regarding our sector in quite some time,” says Payne. “So it’s a really important opportunity to offer feedback to the federal government.”

The federal consultation closes in about three weeks. Individuals and organizations who would like to submit their feedback on the guidance document can do so via email, mail or fax.