Free contraception in Canada: One barrier down, several more to go

Why It Matters

Removing barriers to contraception access gives people agency over their reproductive health and helps narrow the gender equity gap. It also saves taxpayers a lot of money.

This independent journalism is made possible by the Future of Good editorial fellowship covering inclusion and anti-racism in the social impact world, supported by the World Education Services (WES) Mariam Assefa Fund. See our editorial ethics and standards here.

Advocates say free contraception in Canada is a significant step for women’s health, but other barriers to access still need to be addressed, especially for youth.

“Sometimes young people don’t realize they can access sexual reproductive health care on their own,” said Jessica Wood, research and program development lead at the Sex Information and Education Council of Canada.

“They have a right to information and privacy with their health care provider.”

The first barrier: Cost

On Feb. 29, the federal government tabled Bill C-64, the first step for a national pharmacare plan that will begin with coverage for some diabetes medication and prescription contraception.

“The announcement comes on the backs of decades of advocacy. It’s an extraordinary historic win for reproductive rights,” said Insiya Mankani, public information officer at Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights, a non-profit organization that advocates for sexual and reproductive rights.

Gender equality isn’t possible without contraception and abortion access, and removing the most significant barrier to access contraception – cost – will allow people of reproductive age to decide when to have children, she said.

“The reality is people are having to make contraception decisions currently based on affordability rather than what suits their bodies and their lifestyles best,” Mankani said.

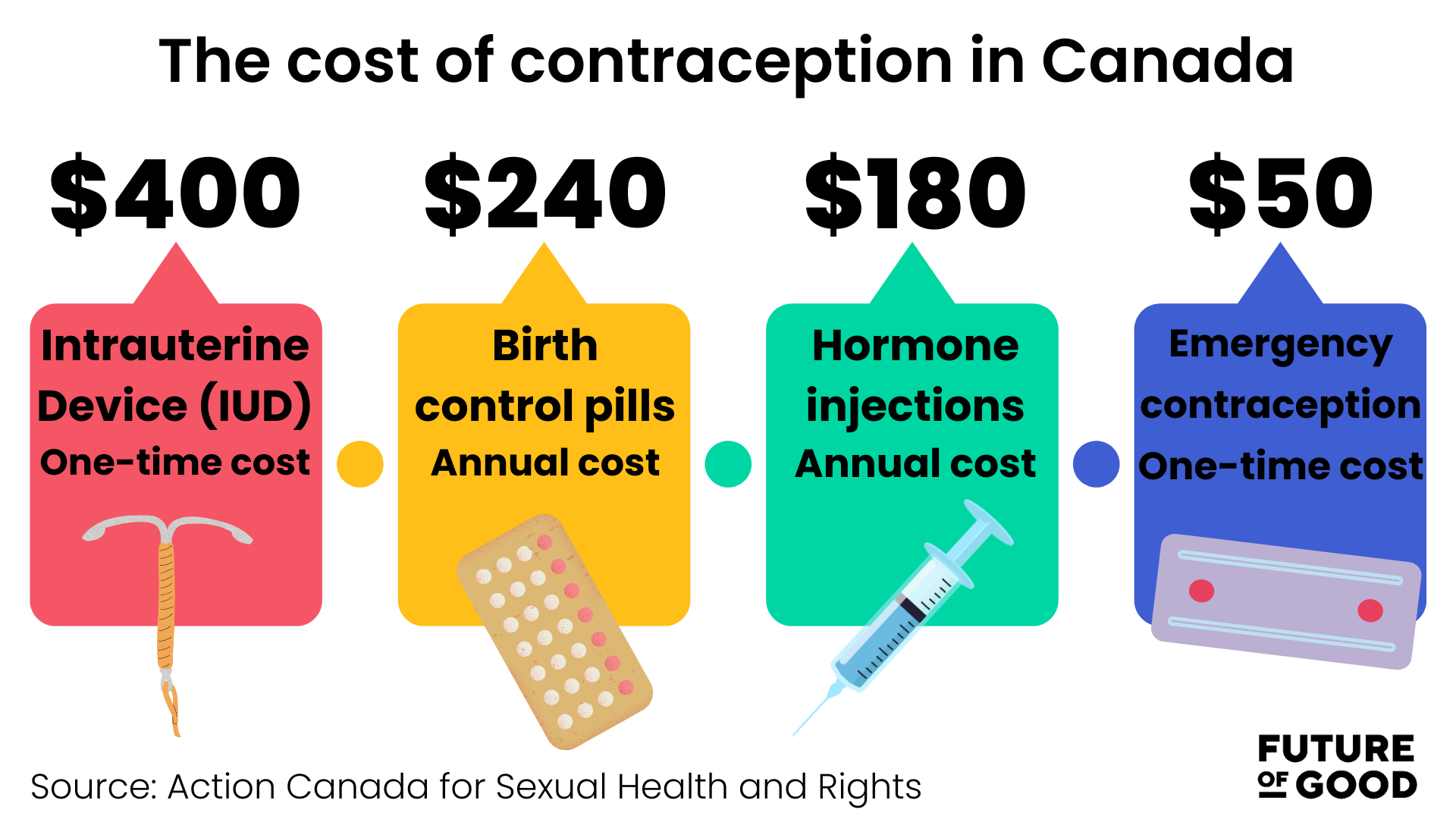

An intrauterine device (IUD) can cost up to $400, birth control pills can cost $20 per month, hormone injections can cost as much as $180 per year, and emergency contraception pills can cost up to $50.

Research also shows that the cost of contraception impacts the choices of young people and marginalized communities the most.

The second barrier: Education

While cost is often cited as the most significant barrier to access, advocates say lack of knowledge about contraception is the next barrier.

Young people who can get pregnant may not know how to get contraception, said Wood.

“There’s a lot of information and evidence that sexual education can improve knowledge of contraceptives and improve contraceptive use,” Wood said, adding that two types of education would be necessary when pharmacare rolls out.

The first should inform people about what pharmacare will cover, where to access it, and how the plan’s offerings may differ from province to province.

The second component is education about contraceptives themselves.

“So, when we can break down some of those barriers in terms of access to information, and access to medications and devices, I think that’s a really big step in terms of ensuring that people have what they need to make those choices,” Wood explained.

Comprehensive sexual health education, including information about STI prevention, is also crucial. Hence, people understand their options, the side effects of medications, and what type of prescription contraception suits their lifestyle best.

Conversations about contraception should be made with a gender-based violence lens and reproductive justice lens, Wood added.

She said organizations that already do sexual health and reproductive health work should get adequate funding to create educational resources that are evidence-based and credible.

“I think it’s also a combination of making resources that are for healthcare providers, educators, and the general public so that people know where to get that information.”

Education should not only be directed at young people but also older age groups that are left out of conversations about contraception, Wood said.

“There’s a lot of people who experience unintended and unwanted pregnancies later in their life. People with children already, people who are in peri-menopausal stages,” she added.

Ensuring that public education about contraception access and use is available should be a priority for the federal and provincial governments when contraceptives become free of cost, Mankani said.

The non-profit sector could play a role in informing both levels of government where some gaps might appear as pharmacare rolls out and also fill knowledge and education gaps along the way, she added.

The third barrier: Easy access

While those in larger Canadian centres can generally access reproductive health care through their doctor or local clinic, it becomes more complex in smaller communities, especially in northern Canada.

A 2015 study called “Barriers and Facilitators to Family Planning Access in Canada” shows northern youth and women have unique challenges accessing birth control.

“These patients have very limited choice in healthcare providers and are not assured confidentiality in settings where they may know everyone working at the clinic,” said the study.

“Many informants offered anecdotes of women hitchhiking hours to find … non-judgmental contraception care.”

As frontline service providers, those who work in reproductive health hear people’s concerns firsthand, said Wood.

“Young people do experience unwanted pregnancies, and having better access to contraceptives can help remove that key barrier,” Wood said.

The Canadian Pediatric Society has also advocated for free and confidential birth control for youth, citing studies that show 25 per cent of youth who do not wish to become pregnant do not consistently use contraception.

Those under age 24 account for about 59,000 unplanned pregnancies annually in Canada, with the direct costs of unintended pregnancies in youth likely exceeding $125 million each year, according to the society.

Most contraceptives will still need a prescription before they are dispensed from a pharmacy, so one way to combat access problems is to allow pharmacists to be given more expansive prescribing authority.

Currently, pharmacists can only prescribe emergency contraception.

In a survey by the Canadian Pharmacists Association, 72 per cent of women said they felt that enabling pharmacists to be actively engaged with screening, prescribing, counselling and managing ongoing contraceptive therapy would result in better access to birth control.

A 2021 paper in the Canadian Pharmacists Journal pointed out that time delays in accessing birth control can result in unplanned pregnancies and abortions.

The fourth barrier: Attitudes

Physician attitudes and culturally inappropriate messaging also keep people from birth control.

The 2015 study showed numerous respondents described experiences with doctors who refused to prescribe birth control.

“We have a physician in our county who will not prescribe birth control because he doesn’t believe in it,” one Saskatchewan doctor told the study authors.

“We have a doctor shortage in our county. They can’t change doctors, and the College of Physicians and Surgeons tell him it’s OK. He doesn’t have to prescribe it. If he doesn’t believe in it, he doesn’t have to.”

Study participants also said messaging around birth control doesn’t always resonate with Indigenous and immigrant communities.

“Much of the messaging about family planning remains culturally irrelevant, focused on ‘preventing births’ rather than ‘planning the family,’” according to the study.

The fifth barrier: Provincial buy-in

Universal access still requires provinces to cooperate with the federal government to roll out pharmacare.

Federal Health Minister Mark Holland told CBC News that he hopes provinces will get involved before the end of the year so people can have access to diabetes medication and contraception.

But not all provinces are on board. Quebec and Alberta have signalled they want to be able to opt out of the universal pharmacare plan, and Ontario and Saskatchewan want to wait and see the plan’s details.

Mankani said she is hopeful provinces will cooperate.

“It is really important for us to have that cooperation between the federal government and the provinces. It is a wait-and-see situation.”

The current proposal for coverage is a universal single-payer system, which means the federal government can negotiate with drug companies to purchase medications in bulk.

A single-payer system means people can get contraception without having to go through private insurance they may share with parents or a coercive partner, said Mankani.

“People do need to have ways to get contraception and make those decisions for themselves.”

No more barriers mean healthcare savings

Nearly 50 per cent of pregnancies in Canada are unplanned, according to the Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians of Canada.

Regardless of the decision people make, there are risks to mental and physical health outcomes as a result of pregnancy.

If the most significant barrier to access – cost – is eliminated, advocates say governments can save millions of dollars in health care related to unplanned pregnancies.

Mankani points to British Columbia, where a universal pharmacare program in the province is close to its first year of providing free contraception.

Researchers estimated its free contraception program will save $27 million in B.C.’s healthcare costs annually.

Nearly 300,000 people received free contraception within eight months under the province’s new plan.

B.C. PharmaCare covers the total cost of more than 60 commonly used birth-control methods, including hormonal pill contraceptives, copper and hormonal IUDs, hormonal injections, a vaginal ring and the morning-after pill.

As the program nears its first full year, advocates in the province want to see additional contraception options covered, such as transdermal patches.

SOCIAL MEDIA: