From training rooms to text messages: saving mothers' lives in Ghana

Why It Matters

Training healthcare workers and using AI-powered SMS technology can boost maternal care in Ghana, offering a practical solution to address critical gaps in lower-income countries.

The semi-enclosed waiting area at Ashaiman Municipal Hospital teemed with all women patients on a hot Monday in December.

The lobby was crowded in the morning, with women having to sit on the floor in the adjacent corridor, but there was no sense of impatience. The numbers steadily dwindled by the afternoon as nurses and doctors dealt with the inflow.

An hour outside Accra, the clean and well-marked hospital is a functional facility serving its community in peace and serenity.

“Previously, we used to have—let me give a rough example—about 100 people a month coming for cesarean sections and other deliveries,” explained Bernice Addo. “But now, we’re seeing 150 to 200 a month,” she said.

Addo, who works in the obstetrics and gynecology ward, sat in the conference room alongside her colleague Gloria Sefako, a midwife at the family planning unit, to discuss the reasons behind the uptick.

They credited the change to recent training Oxfam-Quebec provided to the hospital staff.

“Before the training, we managed through trial and error,” Sefako admitted.

“The major complication we faced was postpartum hemorrhage, which is blood loss—the mother losing too much blood during or after childbirth,” Addo added.

“But after the training, we now know how to manage this stage of labour and respond promptly to the mothers to prevent that from happening,” she said.

Increasing capacity

Oxfam-Quebec facilitated two training sessions at Ashaiman Municipal Hospital in 2024 as part of its Power to Choose intervention to improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

The first focused on teaching the trainers and equipping them to guide others, while the second focused on training midwives. In total, one doctor and five midwives were trained.

The program covered key areas such as newborn resuscitation, postpartum, antepartum and intrapartum hemorrhages, and the management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

It also addressed abnormal labour, such as breech delivery, shoulder dystocia, prolonged labour, and active labour management.

Additionally, the training included comprehensive abortion care, post-abortion care, and the management of young women who have been sexually abused.

“The training has significantly improved the level of care,” Sefako explained, adding she is seeing the impact through increasing client numbers.

“When patients come, they often say someone told them about the good care we provide,” Addo said.

Victims of its success

The hospital is a district-level facility that attracts patients from the Ashaiman district and beyond.

Many referrals come from Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS), the first line of healthcare in underserved areas in Ghana.

While the hospital now has a better-prepared staff thanks to the training, the lack of infrastructure and equipment means it still struggles to accommodate the increasing number of patients.

“If there are no beds, we cannot admit them. Even if we have beds, there are no buildings to accommodate the beds,” Sefako complained.

“Those who can be managed on an OPD basis are treated there, and those with severe conditions are admitted if we have beds available. If we can’t manage them, they are referred to higher-level facilities,” she said.

The referrals – from CHPS to hospitals and between hospitals – are a significant cause of delay that leads to several risks for mothers.

“The complications include eclampsia in people with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, renal disorders, especially in those with hypertension in pregnancy, and anemia—it even leads to death,” Sefako pointed out.

Patients and their families struggle with referrals due to the cost of transportation. “The impact is financial—some don’t have the money to go to other facilities or for transport, like an ambulance,” she said.

“If someone in labour doesn’t have money, she will have to wait for someone to provide the resources before she moves,” Sefako explained.

“They sit and do nothing about it until complications set it,” she added.

A lack of contact with hospitals also creates grounds for misconceptions. “For example, if a facility is nearby and I have a complaint or a question, I can easily go and ask, ‘Why is this happening to me?’ or ‘What does this mean?’” Addo explained.

“But if I live 100 kilometres or even one mile away, it’s much harder to make that trip just to ask a question and then return home. So when facilities are closer, it makes getting education about their problems much easier,” she said.

AI addresses delays

Addo and Sefako describe what’s known as the Three-Delays Model in maternal healthcare with dangerous consequences for the mother and the child: delay in the decision to seek care, delay in arriving at a health facility, and delay in providing adequate care.

While the Oxfam-Quebec training has improved the level of care at the hospital to some extent, delays caused by distances and the lack of quick information remain a challenge. To make verified information readily available, enter PROMPTS.

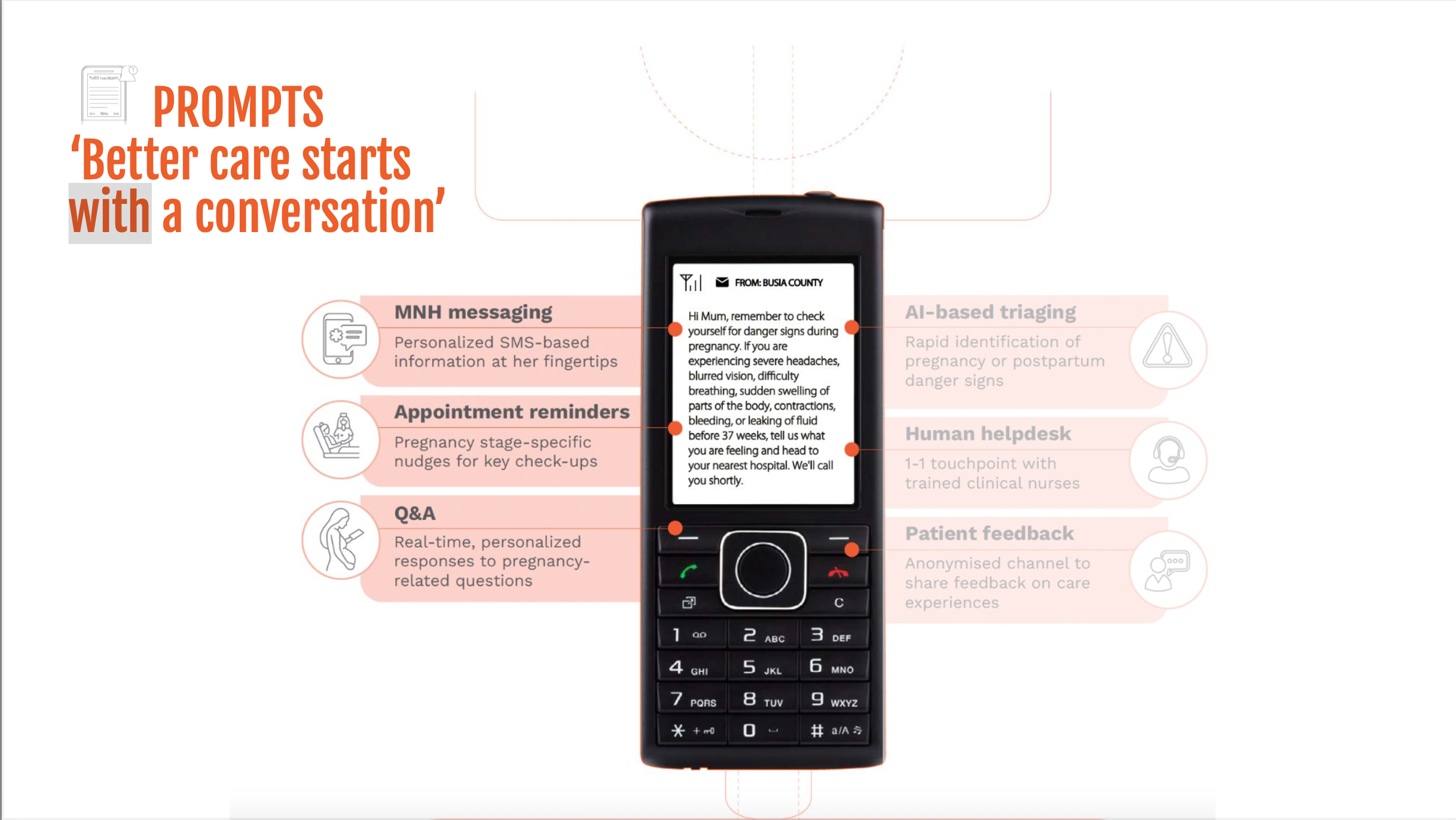

PROMPTS—short for Promoting Mothers in Pregnancy and Postpartum Through SMS—is an AI-based text messaging service that provides information to and responds to questions from pregnant and postnatal mothers and facilitates referrals to hospitals.

“Studies have shown that many causes of maternal mortality are linked to a lack of information. For example, a mother might not know that bleeding is a danger sign and stay home instead of seeking help. Or she might not realize that a severe headache could indicate a serious condition,” explained John Hammond, PROMPTS program coordinator, at his office in Accra.

“The key objective is to empower them with the knowledge to seek care at the right place and time,” he said.

Following its success in Kenya, PROMPTS was piloted in Ghana in two phases in 2023 and 2024, including in the Ashaiman district, by Jacaranda Health.

The service uses text messages to reach its target population.

“We use a basic technology system—SMS—available on every phone. We want to ensure inclusivity, reaching as many women as possible, including those who use non-smartphones,” Hammond said. The service is free of charge.

Cellphone coverage in Ghana is universal, with many households possessing several connections, taking the connectivity rate to 130 per cent. Mothers can voluntarily join PROMPTS by sending a message to the service’s shortcode. The information is provided in both English and the local dialect, Twi.

More than a thousand women enrolled in the pilot program.

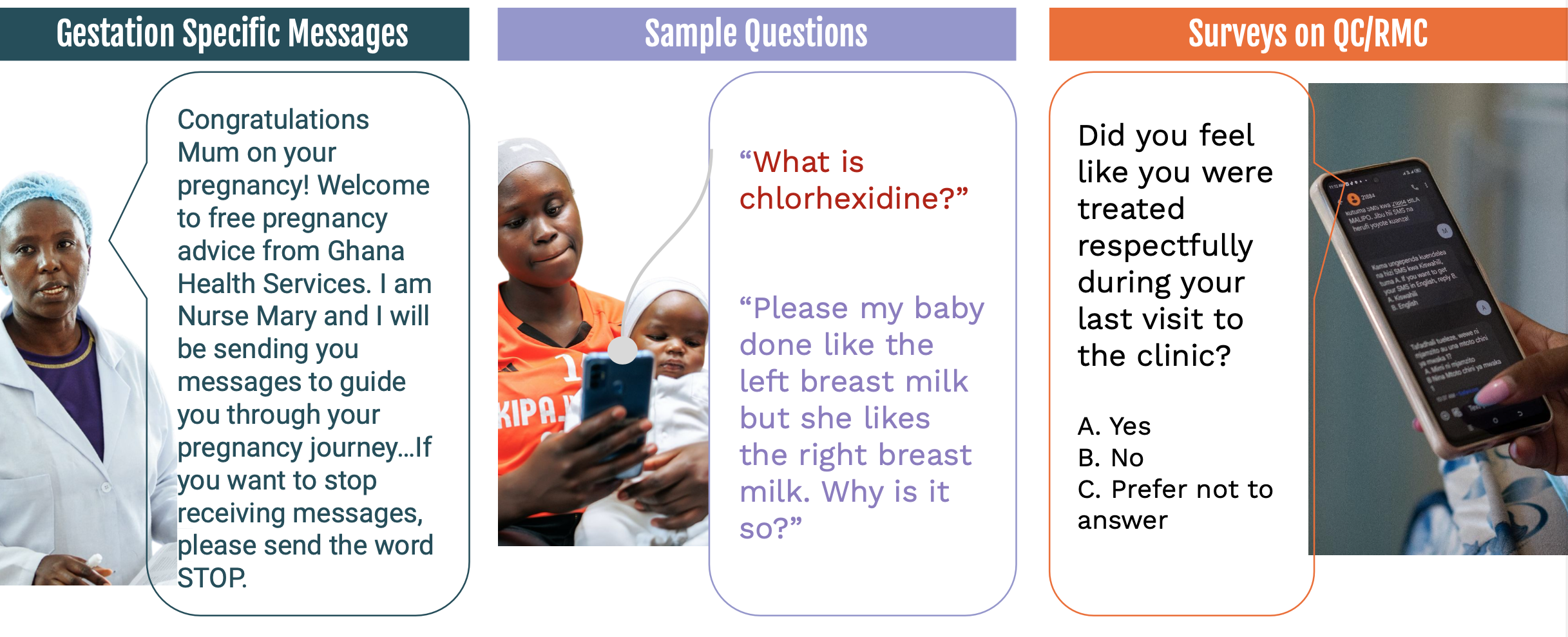

“Every morning at 8 a.m., you’ll get messages tailored to your specific stage of pregnancy,” Hammond explained.

“If a woman is in her first trimester, the messages will focus on first-trimester care. As her pregnancy progresses, the system uses her gestational age to provide messages specific to that stage.

“When she gives birth, the messages automatically switch to postpartum care, covering newborn care and later childcare,” he said

A typical automated message could be, “Mom, if you notice bleeding, swelling of your feet, or dizziness, go to the hospital, but also send us a message.”

The service also sends reminders for routine healthcare visits. “Before a scheduled visit, the woman receives a reminder. Afterward, she gets a survey to provide feedback on the care she received,” Hammond pointed out.

“The strongest aspect of PROMPT is that the information we collect doesn’t stay with us—it goes back to the Ghana Health Service to help improve care,” he argued.

“This feedback is shared with the healthcare facility, which uses it to plan and address gaps,” Hammond explained.

For instance, “we noticed many women asking about UTIs in one facility. After sharing this feedback, the facility started providing in-depth education on preventing UTIs in their community,” he said.

PROMPTS also allows women to interact with help desk agents. “A mother might text about rashes on her child’s skin, asking what to do. These messages go to our agents, who respond based on policy guidelines. If the mother isn’t satisfied with the response, she can ask follow-up questions,” Hammond said.

Denteh Okemanya, a help desk agent, said that while AI sends responses to questions, the human aspect remains central to the service.

“When a question comes in, it goes into the AI system. If the question is not a danger sign—something more benign, like ‘Can a pregnant woman eat eggs?’—the AI pulls a relevant response from the curated pool of answers, such as those related to nutrition,” he explained.

“But before the response is sent to the woman, the agent reviews and verifies it,” Okemanya said.

The value of a human in the loop shows in high-risk cases. “If the system flags it as a danger sign, it bypasses the AI and goes straight to the agent, who then calls the woman,” he added.

Elizabeth Oduro, another help desk agent, shared an example:

“A mother flagged in that she couldn’t breathe. I immediately recognized this as a danger sign and referred her to the hospital. Because she had been interacting with us and trusted that the advice was from a clinician, she followed it and went to the hospital.

“We followed up, and she was admitted to the hospital, where she was stabilized within three days and discharged.”

In addition to emergency intervention, phone follow-ups ensure service delivery. “It’s not enough to provide information and assume mothers will act on it,” Oduro insisted.

“We typically follow up three times: first to check if they’ve gone to the facility, second to ensure they’ve received appropriate care, and third to confirm they’ve been discharged and are doing well,” she explained.

Surveys by Jacaranda show that 74 per cent of mothers who were told to seek care went to hospitals, while 94 per cent who were sent reminders went to their appointments.

“All the responses we send are audited weekly by a quality assurance consultant,” Okemanya said.

“The consultant reviews our responses and guides us on how we could have handled certain situations better,” he added.

The program’s internal evaluations show positive feedback from mothers. “They always send me messages, and I reply. Sometimes, when I ask questions, they reply. So, it is very easy,” responded one woman in antenatal care at Tema General in Tema Metropolis.

Another, in postnatal care at the neighbouring Manhean Polyclinic, said, “I’m a first-time mom, so it has been very helpful because it teaches me how to handle the child, in terms of food to give the child at various stages or whether or not to give the baby water.”

Hammond noted it is “not the AI that simply generates responses to women’s queries on its own.”

Instead, “these responses have been carefully curated over the years and are rooted in policy. They incorporate country-specific, contextual information,” he explained.

PROMPTS collaborates with healthcare professionals on the ground and does not exclude them.

“We are simply complementing the work midwives do—we are not replacing them. Some fear AI will take over jobs, but that is not the case here,” Hammond said.

“We are using existing, policy-related health information specific to this country. We have converted this information into digital formats and now share it with mothers. So, this is not entirely new; it’s building on what already exists,” he explained.

Bringing healthcare closer to home

Back in Ashaiman, Oxfam Ghana’s public engagement lead, Archibald Adams, supports Addo and Sefako’s view that mothers require healthcare services as close as possible to their homes and that the pressure on Ashaiman Municipal Hospital must be reduced.

“We need to look at how we can pass on the knowledge to the smaller units so that bit of management can extend to those levels,” he suggested.

That way, the “pressure on you also goes down until you have the logistics to contain all these numbers,” he said to the two nurses.

Fauzia Abdul-Rahman, project coordinator for Power to Choose, mentioned other initiatives where midwives at CHPS have been trained. She agreed with her colleague, noting the positive impact of training staff at smaller health facilities.

For Hammond and his colleagues in Accra, the solution to bridging this gap is to reduce the first delay in maternal care: delay in information. They have the data to back their claims.

Jacaranda had set an initial target of 10 per cent of mothers asking questions and an overall interaction rate of 50 per cent. The organization’s data shows that 65 per cent of pilot participants asked a question or responded to a survey, surpassing expectations. Over 2,000 questions were asked by participants, with most of the queries on general pregnancy-related issues.

Jacaranda Health plans to expand the text-based intervention one district at a time until it reaches full coverage in Ghana.

Like in Kenya, where PROMPTS has served around three million mothers, the Ghana program also aims to eventually integrate transportation, such as ambulances, into its services to reduce delays in getting care even more.

“We’re essentially bringing healthcare closer to mothers through their mobile phones,” asserted Oduro.

“We’ve turned phones into pocket hospitals.”