Housing hot button: Should your foundation divest from residential REITs?

Why It Matters

For endowed foundations, where they invest has the potential to boost their impact beyond their granting — or work at cross-purposes with it. More information would help foundations make informed decisions.

Tamara Herman, associate director of capital strategies at SHARE, a non-profit shareholder advocacy organization. Photo: Joshua Berson

Tamara Herman, associate director of capital strategies at SHARE, a non-profit shareholder advocacy organization. Photo: Joshua Berson

Experts say foundations should take a close look at their investment portfolios after a recent report revealed a troubling lack of information around affordability, eviction rates and building maintenance at Canada’s six largest residential real estate investment trusts, representing more than 125,000 housing units.

Published by SHARE, a non-profit shareholder advocacy organization, the report analyzed data from 2021 and 2022. It found that none of the six investment trusts, also known as REITs, disclosed enough information about their practices to allow investors to make informed decisions.

“There’s been a real push to align foundations’ investment portfolios with their missions and their beliefs, and it’s really difficult to do that if the companies in your portfolios aren’t providing you with the type of information you need to understand what the impact of your investments are,” says Tamara Herman, associate director of capital strategies at SHARE and the report’s co-author.

The limited information available to SHARE suggests Canada’s largest residential REITs are using apartment turnovers and renovations to boost rents, decreasing affordability for Canadian renters and potentially causing “adverse human rights impacts.”

New tenants saw an average rent increase of 13 per cent over previous tenants at properties owned by the four REITS that provided affordability data in 2022; Canadian Apartment Properties Real Estate Investment Trust had the highest increase at 14.5 per cent.

The report also found tenants who rented newly renovated suites faced much higher rents than previous tenants.

Post renovation rents were 25 to 29 per cent higher than pre-renovation rents at Apartment Real Estate Investment Trust and Killam Apartment Real Estate Investment Trust — the only trusts to publish this data.

The report’s authors say these findings should be of concern to investors and that all shareholders are responsible for upholding human rights — including the right to adequate housing.

Canadian foundations and charities aren’t required to disclose their investments, but interviews with experts suggest residential REIT holdings are common.

Greg Rodger, chief investment officer of HighView Financial Group, says most of his firm’s 20-odd charitable sector clients have exposure to private market residential REITs. Two foundations that co-sponsored SHARE’s report — the Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation and the Atkinson Foundation — also told Future of Good they have some residential REIT exposure.

Ricardo Tranjan, senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives says Canadian foundations should divest from residential REITs, arguing these investments are a “no-win” scenario from an ethical perspective. Courtesy: Ricardo Tranjan

Ricardo Tranjan, senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives says Canadian foundations should divest from residential REITs, arguing these investments are a “no-win” scenario from an ethical perspective. Courtesy: Ricardo Tranjan

An unethical investment or model provider?

Residential real estate investment trusts first appeared in Canada in the 1990s. Modelled on American funds, they provided middle-class investors with easy access to commercial real estate. Over time, they evolved to facilitate investment in other types of real estate, including apartment buildings, self-storage facilities and hospitals.

Regardless of property type, REITs pool investor capital to purchase, operate or finance real estate. Profits are then generated through rent and investors receive cash distributions, usually on a monthly basis.

These distributions tend to be higher than stock or bond dividends, which make them attractive to foundations, Rodger says. They also tend to increase in value over time.

“If you think about it, the cash distributions are really a result of the net rent collected on the properties that are owned — and those rents typically are increasing over time,” he says.

But while this business model has made REITs attractive for investors, some say it also leaves them vulnerable to criticism.

“[Investors have] to ask themselves, ‘Why is the deal so good?’” says Ricardo Tranjan, a senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. “[It’s because] someone else is bearing the risks — and it’s largely low and moderate income families.”

Tranjan says sky-high housing costs in Canada are not the result of a so-called “housing crisis,” but rather a “fundamentally unjust housing market.” Investing in REITs is a “no-win” position from an ethical perspective for Canadian foundations because the business model is predicated on buying housing supply that is limited and then increasing rent, he says.

Tranjan, who was not involved in the SHARE report, says studies have found REITs to be more “aggressive” than other types of landlords, including by pursuing above guideline rent increases.

In Ontario, provincial regulations limit annual rent increases, but landlords can exceed the maximum allowable rent increase through a special application process if they made significant renovations to their buildings or incurred other large expenses.

A report analyzing the Toronto housing market found “financialized landlords,” including REITs, secured more above guideline rent increases than their “independent landlord” peers, despite owning fewer units, between 2012 and 2019.

During this period, the Canadian Apartment Properties Real Estate Investment Trust secured above guideline increases for over 22,000 units in Toronto — the most of any landlord, according to the report.

Future of Good contacted all six REITs featured in SHARE’s report, but none of the trusts agreed to an interview.

But in a recent Toronto Star op-ed, CAPREIT’s CEO Mark Kenney refuted Tranjan’s characterization of REITs, describing them as a “model rental housing provider” and a key part of the solution to reducing housing prices across the country.

Kenney argues it’s a lack of housing supply that’s driving rent up and that the “dogmatic fixation against corporate investment in housing” is chasing away the necessary capital to build more units.

The Canadian Apartment Properties Real Estate Investment Trust is also part of a coalition of REITs lobbying the federal government to maintain preferential tax treatment. The trusts are currently exempt from paying corporate taxes if they distribute their taxable income to shareholders, referred to as unitholders.

In response to concerns raised by housing advocates, the federal government promised to review REIT taxation in its 2022 budget, but no details have followed.

Divestment or shareholder engagement?

For Tranjan, the solution to ethical concerns about residential REITs is simple: divest existing holdings and update your investment policy to preclude future REIT investments.

Some foundations are already moving in this direction.

Mike Thiessen, co-chief investment officer for Genus Capital Management, says “very few” of his clients hold residential REIT investments, and some have chosen not to invest for “values-based” reasons, including concerns about REITs purchasing social housing and converting units into luxury apartments, he says.

If foundations have serious reservations about REITs, the Vancouver-based investment manager recommends they open a “custom mandate” portfolio with his firm and ask for residential REITs to be avoided.

Tranjan says divestment is the most impactful move, as few foundations likely hold enough REIT units to be able to compel better corporate behaviour through shareholder activism or engagement.

Colette Murphy, CEO of the Atkinson Foundation, disagrees.

The private foundation focuses on social and economic justice, and has roughly $110 million in assets. When Murphy spoke with Future of Good in mid-July, Atkinson was invested in two REITs — neither of which were profiled in SHARE’s report — through equity funds.

“[We believe that by] working together as consumers of financial services, investors can influence corporate conduct, and influence the behaviour of financial markets over time,” she says, adding the Atkinson Foundation worked with SHARE to submit seven shareholder proposals recommending corporate action on social and economic issues over the past two years.

Last year, one of the proposals succeeded, pushing construction company Toromont Industries Ltd. to take action on Indigenous reconciliation.

Murphy says SHARE’s report is helpful for her foundation because it provides a list of seven human rights-related metrics against which REITs can be measured. She says Atkinson will discuss these metrics with their investment managers, asking how they review and assess REITs.

Herman hopes more foundations will take this approach.

“All investors have a human rights responsibility,” she says. ”We’re simply saying that in order to perform human rights due diligence investors should be asking REITs some questions.”

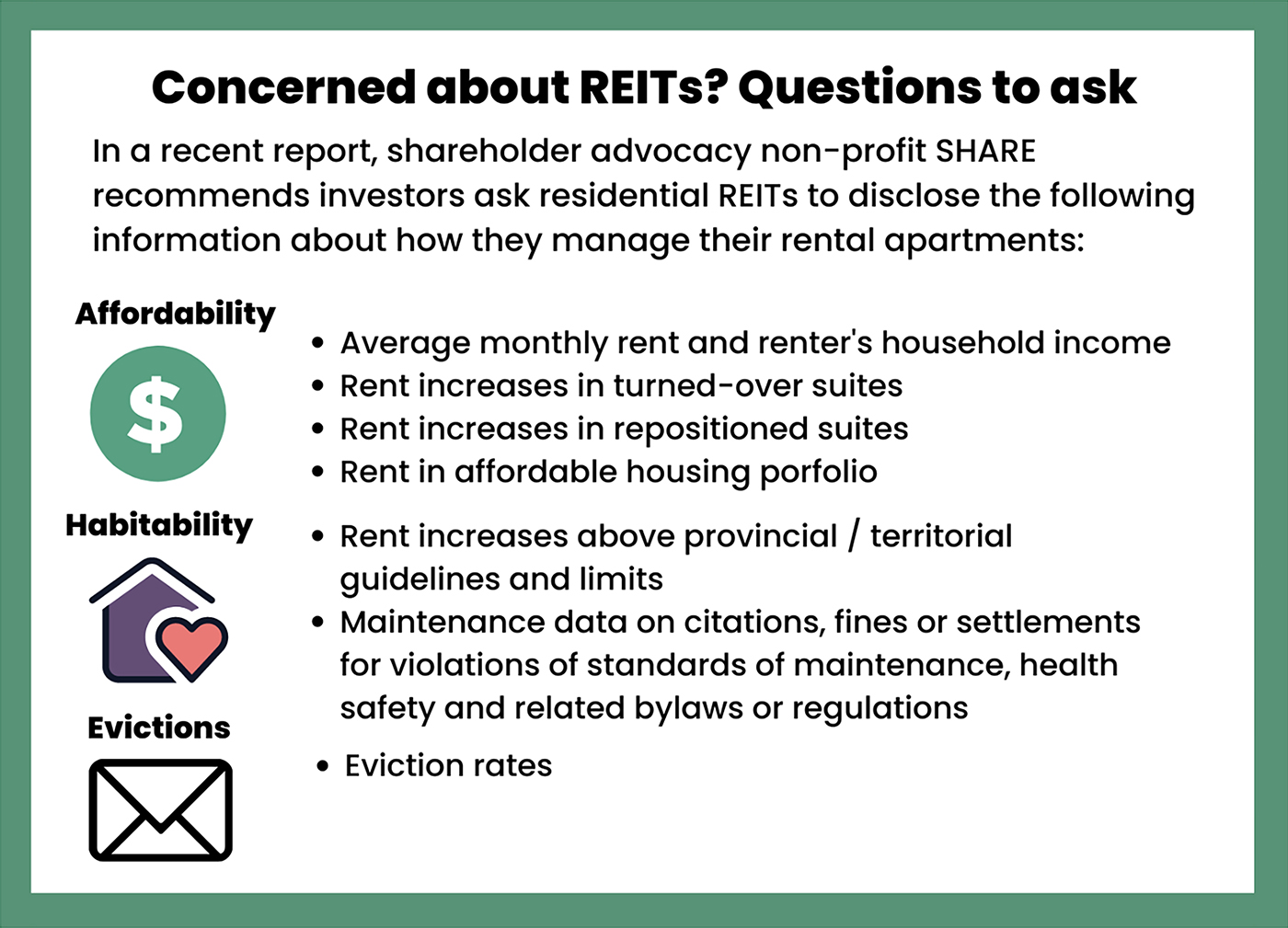

Published in May 2023, SHARE encourages investors to ask residential REITs to provide information about their approach to suite affordability, unit habitability and evictions. Graphic: Gabe Oatley

Published in May 2023, SHARE encourages investors to ask residential REITs to provide information about their approach to suite affordability, unit habitability and evictions. Graphic: Gabe Oatley

The affordable housing option

Foundations concerned about access to housing in Canada can also go beyond the question of divestment and invest more money directly into the development of new, purpose-built affordable housing, says Tranjan.

The Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation, Canada’s third largest foundation with over $2 billion in assets, has done work in this area. It’s committed to investing about $60 million in affordable housing projects — a figure that eclipses the $200,000 currently invested in Canadian public residential REITs, according to the foundation’s senior communications advisor, Marie-Zélie Sainz.

The United Church of Canada has also focused its funds on this problem. With congregation attendance dropping, the organization has invested about $10 million in redeveloping church properties through a firm called Kindred Works.

Wholly owned by the United Church of Canada, the firm has 25 projects underway and is aiming for one third of units to be below market rate.

Rendering of a 12-story development project in Toronto proposed by Kindred Works, a property development firm owned by the United Church of Canada. Image: Kindred Works

Rendering of a 12-story development project in Toronto proposed by Kindred Works, a property development firm owned by the United Church of Canada. Image: Kindred Works

Erik Mathiesen, United Church of Canada’s chief financial officer, says affordable housing work may be the church’s new “social gospel.”

When health infrastructure was nascent, churches created some of Canada’s first hospitals, he says. Today, healthcare is a government responsibility, housing affordability is top of mind, and the church has abundant real estate. “Affordable housing might be our [social gospel] 2.0,” Mathiesen says.

Tranjan says he’s hopeful more foundations turn their attention to the issue.

“Most foundations believe that ‘do no harm’ is a valid principle,” he says. “With resources comes responsibility.”