How $335 million and a Wall Street-inspired funding model have raised hopes for the conservation of the Great Bear Sea

Why It Matters

Much environmental conservation focuses on preserving land piece by piece. A new model focuses on increasing the long-term resilience of an entire region by funding it up-front.

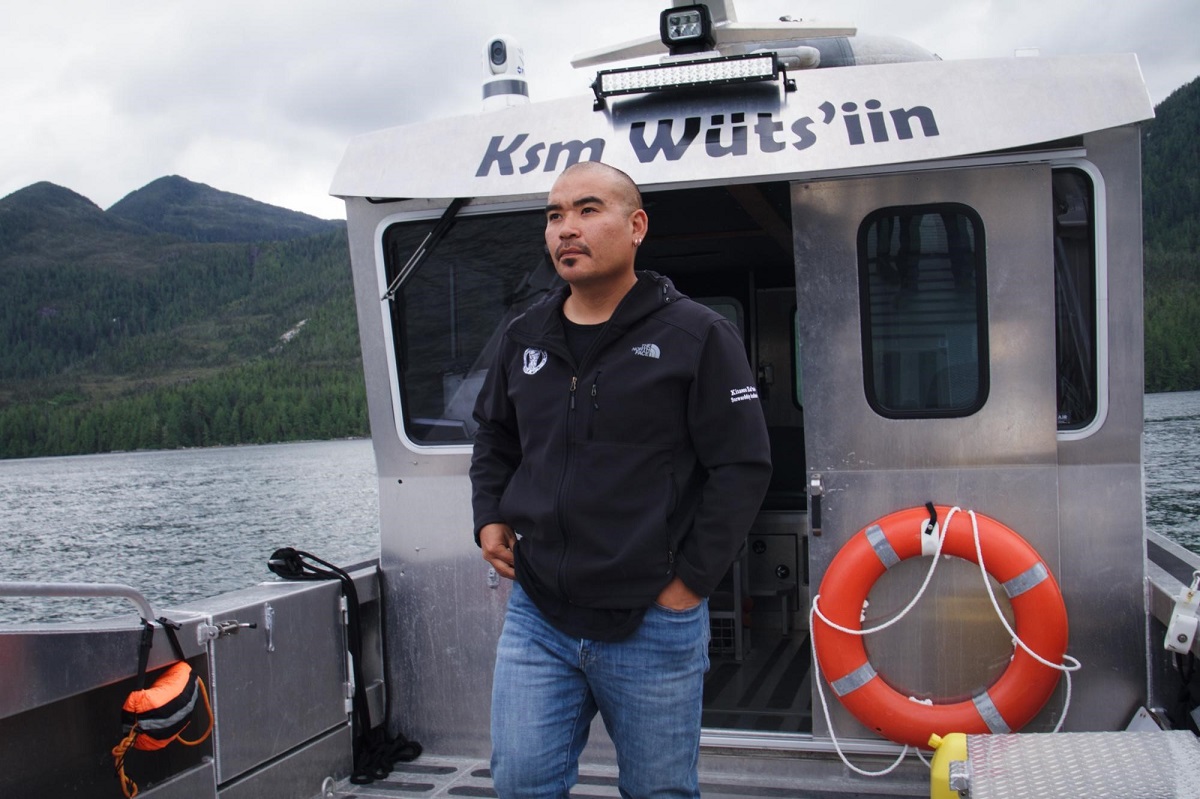

As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced an ambitious new conservation project in late June, Chief Douglas Neasloss of the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation felt tremendous relief.

The announcement realized a decades-in-the-making vision for conservation—one where coastal First Nations will co-govern management of the Great Bear Sea in true partnership with settler governments.

The relief stemmed, he said, from the knowledge there is now sufficient money to manage sorely needed conservation work.

In recent years, once plentiful salmon stocks have declined due to commercial overfishing, the cumulative effects of shipping, and climate change, he said.

The same goes for the presence of abalone, a flavourful sea snail.

Fished for millennia by Kitasoo Xai’xais people and other coastal First Nations, the mollusk is now endangered after unsustainable commercial fishing in the mid-20th century.

Most Kitasoo Xai’xais youth have never tried one, he said.

“We’re an ocean-based people, a salmon people,” said Chief Neasloss. “We depend on the ocean for our food, for our transportation. It connects to all the other communities.”

Seeking to address these and other challenges, the new $335 million initiative uses a project finance for permanence (PFP) model. It’s an innovative approach to conservation inspired by a Wall Street financing tool.

Supported by Indigenous people and funders alike, it’s gaining traction globally.

A tweak on a Wall Street financing model

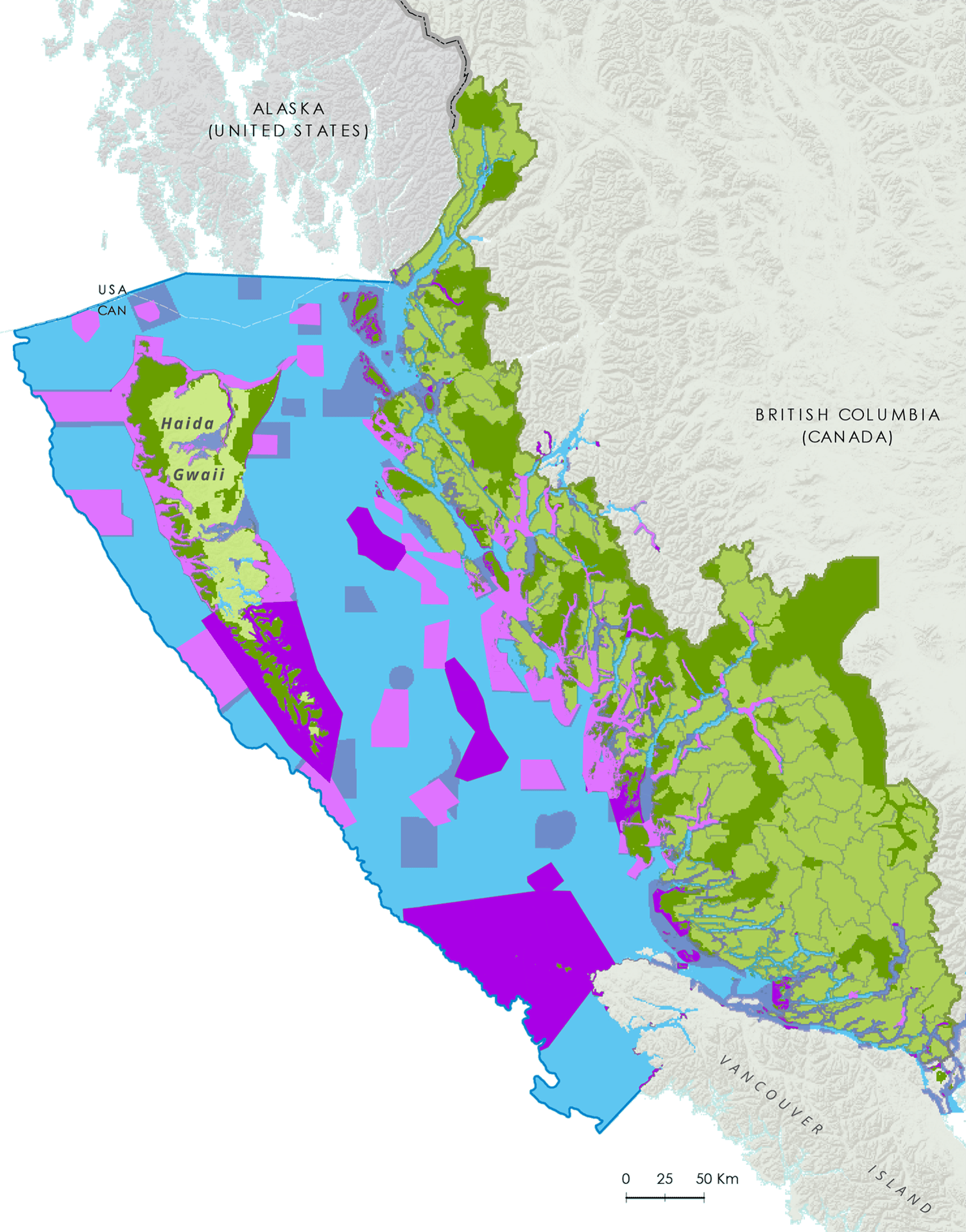

Conservation projects aren’t new to the Great Bear Sea, an area in the Pacific Ocean known as the Northern Shelf Bioregion, which extends from northern Vancouver Island to the Canada-Alaska border.

What is precedent-setting, however, is that the entire project was Indigenous-led and designed, said Alana Ferraro, director of philanthropy for Nature United, an initiative partner.

The PFP approach is also special because it offers “durable” conservation at scale, she added.

While many conservation efforts focus on protecting land one tract at a time, PFP initiatives set conservation targets for whole regions, aiming for long-term resilience.

Through the project, partners aim to conserve 10 million hectares of ocean—an area roughly the size of Iceland—home to dense kelp forests, killer whales, and sea otters.

Under the agreement, First Nations and settler governments will co-govern and implement the Marine Protected Area Network Action Plan, a document that outlines specific guidance for permissible activities in distinct parts of the ocean.

Unlike piecemeal conservation efforts, the PFP model is also built to last, say experts.

Before launching the initiative, the First Nations-led project team developed a detailed financial model outlining the project’s near-term and future conservation costs.

With a budget in hand, they then fundraised to meet those targets, securing $335 million—$200 million from the federal government, $60 million from the Province of B.C., and $75 million from philanthropic funders.

This approach—called project finance—is commonly used to raise sufficient capital for large infrastructure projects. But it’s much less typical in the charitable sector, where project-based grants are more common.

Yet Chief Neasloss views this model as the right one for conservation.

“Stewardship is expensive,” he said. “We can’t just protect an area and expect that a line on a map will [cut] it. We need to put a lot of time, effort and money behind it. This is the way forward—hopefully, globally.”

From protests to community prosperity

The chief is confident in the model because he’s seen it work before.

In 2006, coastal First Nations struck a landmark agreement with the Province of B.C., environmental groups and forest companies, ending years of Indigenous-led protests against widespread and destructive logging of the Great Bear Rainforest.

Now recognized as the world’s first-ever PFP, the resulting agreement set policy for permanently protecting more than six million hectares of temperate rainforest on B.C.’s north and central coast—an area the size of Ireland.

Subsequent negotiations resulted in the Federal and B.C. governments contributing a combined $60 million to a fund for partnering coastal First Nations’ economic development.

Private funders also seeded a second $60 million fund, which has been used since to provide long-term support for First Nations-led environmental conservation in the area.

For the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation, the project has been a success, said Chief Neasloss.

Before the agreement was struck in the 1990s, unemployment was high among his community of about 350 people, and wildlife suffered due to a “wild west” of illegal logging and hunting, he said.

The PFP’s conservation policies and funds have helped turn things around.

Since 2006, the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation has secured about $6 million from the economic development fund, investing heavily in Spirit Bear Lodge—an eco-tourism and adventure travel business.

The enterprise has thrived, creating about 40 jobs and helping the nation reach nearly full employment, Chief Neasloss said.

Illegal extraction has also largely been stopped, in part due to the success of the nation’s guardian program, which pays community members to monitor and manage the conservation agreements covering Kitasoo Xai’xais territories.

Now, Chief Neasloss hopes to see the same success in the ocean.

Model combines endowment and spend-down funds

Aligned with the model to protect the rainforest, the PFP to preserve the ocean also focuses funds on both conservation and community economic development for the short and long term.

Of the project’s total $335 million, $167 million will fund a marine stewardship-focused endowment managed by conservation finance charity Coast Funds.

This fund will be maintained in perpetuity, using both traditional Indigenous knowledge and science to help preserve and protect 84 at-risk species, according to project partners.

The endowment model is critical for conservation because it gives First Nations confidence that funds will be available to move their conservation projects from ideation to implementation, said Coast Funds CEO Eddy Adra.

This model also enables conservation capital to grow, he adds.

In the mid-2000s, Coast Funds was created to manage the funds associated with the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement.

Since the launch of its $60 million conservation endowment fund, more than $70 million has been generated in interest—money that will support further projects protecting the Great Bear Rainforest for years to come, Adra said.

As with that initiative, the Great Bear Sea PFP also allocates an additional $120 million for a fund focused on First Nations’ community economic development, including providing support training, culture, and language programs.

This fund will be spent down over the next 10-15 years, Adra said.

The final $48 million of the Great Bear Sea PFP money will provide operational funding to help implement the co-governance of the project’s conservation agreements.

Project partners estimate the combined investments will stimulate 3,000 new jobs, 32,000 days of skills training, and contribute to the federal government’s goal of conserving 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030.

A draw for funders

In addition to its popularity with First Nations, funders have welcomed the project finance for permanence model.

More than 20 institutional funders supported the Great Bear Sea PFP, including the Bezos Earth Fund, MakeWay, and the Ronald S. Roadburg Foundation.

For the Sitka Foundation, another Great Bear Sea PFP funder, the motivation to help was the chance to support an initiative with the potential to create a broader and more permanent impact than could be achieved by funding any individual organization alone.

“The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” said foundation executive director Carolynn Beaty.

In addition to offering funding, the Sitka Foundation supported the PFP by helping to recruit other foundations to contribute to the project.

Other PFPs underway in Canada, globally

In addition to the new Great Bear Sea PFP, at least three other PFPs are in development nationwide—one in northern Ontario, one in Nunavut, and the fourth in the Northwest Territories.

In December 2022, the federal government committed $200 million for each of these four projects at the COP15 summit in Montreal.

Several other PFPs have also been launched globally.

In April, the Mongolian government announced a new U.S. $200 million project finance for permanence initiative, which includes U.S. $71 million in private donor funding.

The funding aims to expand and strengthen the effectiveness of the country’s existing network of conserved land, support sustainable herding, and invest in the local tourism industry, according to a press release from the Nature Conservancy, a project partner.

Governments in Bhutan and Brazil have also used PFPs, aiming to advance national conservation objectives.

A new model, advancing an old vision

Chief Neasloss said he wishes his elders had lived long enough to see the Great Bear Sea PFP agreement struck.

They pushed for years to make something like this happen with little success, watching as others made decisions in Kitasoo Xai’xais territories, he said.

But no longer.

The PFP’s durable funding will enable his people to negotiate conservation agreements in true partnership with other First Nations and settler governments, he said.

In addition, the endowment funding means the conservation programs will last forever.

“Our kids’, kids’, kids can depend on this,” he said.