HOW TO: Four steps to building a weekly data collection process

Why It Matters

While a weekly data collection process is a time-intensive commitment, it can provide a real-time view of priorities, challenges and needs among a specific participant group.

When Paloma Raggo, associate professor at the School of Public Policy at Carleton University, proposed a weekly data collection project about the state of the Canadian charitable sector, fellow academics and non-profits were skeptical. They raised an eyebrow at the pace at which a research team would have to work to collect and analyze data every single week.

Undeterred, the director and principal investigator of the Charity Insights Canada Project / Projet Canada Perspectives des Organismes de Bienfaisance (CICP-PCPOB) and her team of researchers collected this information for an entire year.

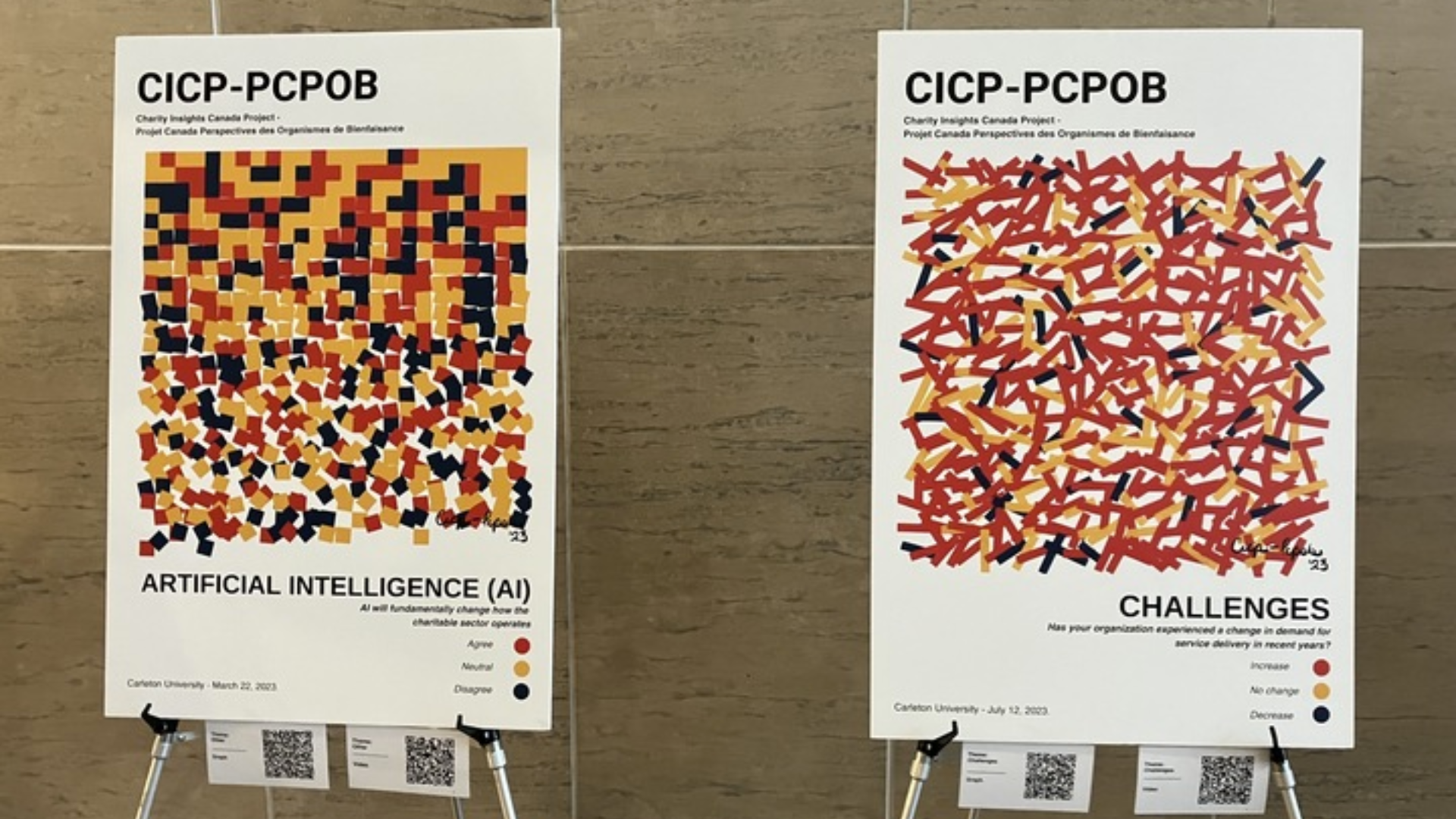

Every week, Raggo and chief project officer Callie Mathieson sent out a weekly survey, in English and French, to a randomized sample of organizations in the non-profit sector. Surveys were relatively short and usually focused on a timely issue, such as artificial intelligence, financial stability, volunteer recruitment and Indigenous participation.

In November 2023, the team collated the results of the weekly surveys into a mid-year report, identifying recurring themes from a year of data collection. The report identified several pressing and timely issues that non-profits face, such as financial challenges, decreased volunteerism, and an increased likelihood of burnout among staff.

Since Canada’s last national survey of the charitable and non-profit sector occurred 20 years ago, CICP-PCPOB is filling a crucial information gap.

“The Director General of the CRA’s Charities Directorate has our reports on their desk,” said Raggo. “StatsCan and Employment and Social Development Canada are asking us to meet. It’s not just about our data, but our approach [to collecting it.”]

Reflecting on the first year of collecting data every week, both Raggo and Mathieson say that the pace of gathering and disseminating this information is challenging. But as a tight-knit team of two with transparent processes, it has become a repeatable exercise over time.

“Clear procedures [for research] save us a lot of time,” Raggo said. “We debate on wording [of questions] and challenge each other very openly. We try not to be polite because we don’t have time.”

As the CICP-PCPOB team selects its research participants for the project’s second year, they can include new organizations in the surveys, ask the same questions, and observe how responses have changed year-over-year.

Future of Good sat down with Raggo and Mathieson at the CICP-PCPOB’s Annual Data Summit in November to learn more about what it has taken to build, test and iterate their weekly data collection process.

-

Create a committed and reliable list of research participants

The first step was to collaborate with the Canadian Hub of Applied Social Research (CHASR) at the University of Saskatchewan to build a randomized sample of non-profits. This sample would then comprise the participant panel, to which the CICP-PCBOB team would send surveys weekly.

Enlisting a third party to create the sample lists meant the research team was at arm’s length from the recruitment process. Still, it also allowed them to create some subsamples that could warrant further research, such as foundations and volunteer-run charities, Mathieson added.

Using the randomized samples, CHASR created outreach lists for the CICP-PCPOB to reach out to potential panelists. The research team successfully recruited a panel of 1,074 charitable organizations across Canada, excluding religious organizations, hospitals and schools, making sure to over-recruit.

Early in the weekly data collection process, the research team removed organizations that had agreed to be on the panel but had not responded to any surveys for the first eight to ten weeks. Raggo also said some organizations are committed enough to have asked to be part of the panel again in the project’s second year.

-

Plan research objectives with a degree of flexibility

Raggo, Mathieson and the research team planned out research questions roughly six weeks before sending the survey to the panel. However, given that the nature and point of the research project is to discover instant priorities in the sector, Mathieson said there also needed to be some flexibility in how the research questions were planned and disseminated.

“We keep things flexible enough so that if we see something interesting [in the results], we can slip another question into a subsequent survey,” she added. “We should be asking about something when the sentiment is fresh.”

For example, Raggo noted asking the panel about their perspectives on artificial intelligence was a spur-of-the-moment decision based on the research team’s work in leveraging ChatGPT. Another example of an immediate priority was the impact of inflation on the charitable sector.

While weekly research can help the team understand the sector’s reaction to challenges as they arise, Raggo also said there is a balance to strike between the immediacy of the data and its long-term relevance.

“We ask each other whether certain questions will be interesting or relevant for further research,” she said. “If it’s not, we don’t ask.”

-

Incentivize and excite research participants.

In research practice, Mathieson observed that if you want participants to stay with a survey long-term, you have to offer compensation. For the CICP-PCPOB team, financial or monetary incentives weren’t possible.

“The compensation was the data itself,” Raggo said. “Researchers ask [non-profit] practitioners to give a lot of their time, but they rarely see the return on investment.”

Here, because participants receive the complete breakdown and analysis of the results each week, they stay engaged.

“There is a lot of literature on ‘survey burden,’” Raggo added. “How can we find the right balance between minimal time commitment and maximum return?” The team structured the surveys around three or four weekly questions to reduce the time commitment.

While the research team recognized that asking respondents to fill in weekly surveys is burdensome, they also realized there was value in it becoming part of participants’ routines to keep responding. Now, if Mathieson sends the survey out later than usual, respondents are asking her upfront where that week’s survey is.

-

Build a replicable data analysis process

Through the questions the CICP-PCPOB team asks each week, quantitative and qualitative information is collected. They use Qualtrics to represent the quantitative information and NVivo to categorize the qualitative responses. The team is also experimenting with chatbots and AI and embedding technologies into the data analysis process.

Qualitative analysis is a time-consuming process that does not fit well within the project’s weekly schedule. Instead, Mathieson publishes the written responses in the weekly reports as a list and creates a word cloud if specific answers can be clustered into themes. The team analyzes and draws conclusions from the qualitative data more thoroughly in monthly reports.

“Every week, we try to move away from text-based questions because response rates are usually lower for those,” she added. In the survey’s early iterations, the team didn’t allow respondents to mark an answer as “not applicable” or “not sure,” which Mathieson said was an oversight.

“I started to look more into the best surveying techniques, and it was clear from panellists’ feedback that certain questions might not apply to every type of [non-profit] organization.”

“I see our [analysis] approach in three stages,” Raggo added. “We get descriptive analysis right away, based on what people have said and basic counts. The second step, for the monthly and mid-year reports, is where we try to integrate results across questions and broader themes.”

“The third stage is understanding factors that affect certain decisions or behaviours [in the charitable sector]. We use complementary [external] data to predict the conditions under which a charity will experience something. This is more technical and academic and requires a bit more mulling and time.”