How UK funders quickly mobilized against racist violence

Why It Matters

This summer’s violent attacks on Muslim and other racialized communities in the UK revealed deep-seated tensions. With more data – and strategies that incorporate insights from that data – funders can actively direct capital towards projects that help prevent future violence.

In early August 2024, when racist riots broke out across the UK, Fozia Irfan was quick to convene an emergency meeting of funders.

“Philanthropy has a critical role to play in times of crisis – that is when we are most needed and we have the independence, resources and capacity to act quickly, in a way that other sectors can’t,” said the director of impact and influence at BBC Children in Need.

“The riots were deeply traumatizing for many communities, and as foundations, if we purport to always be acting for public benefit, we need to step up when our communities and charities face these critical issues.”

Riots erupted across several British towns and cities in the summer, following the murders of three young girls in the northern town of Southport. Misinformation circulated about the perpetrator being Muslim and an asylum-seeker, which fuelled numerous anti-immigration protests all over the UK.

Amid widespread damage, protestors attacked a mosque and various hotels housing asylum seekers. Many were linked to a now-disbanded far-right group.

In some cities – including London – counter-protestors came out in the thousands, protecting vulnerable communities and infrastructure.

Foundations also jumped into action. Many made statements of support and solidarity with racialized communities, while others made rapid funding available to grantees.

Non-profit leaders and staff working in the migration sector also asked for funding to be made available to support the wellbeing of their staff, particularly those with lived experience of racist hatred.

“Collaboration between funders can help get more money to grassroots organisations quickly and efficiently by drawing on established networks and distribution mechanisms,” wrote Jim Cooke, head of practice at the Association for Charitable Foundations.

On social networking site LinkedIn, Irfan asked what funders could do for those working in charities and communities affected by the riots.

One person asked funders to “reflect on their ‘blind spot’ and at times intentional erasure of religion as a deserving category or lived experience as worthy of funding”, while others called for unrestricted funding, multi-year commitments and removing lengthy reporting procedures.

“These are deep-seated and historical issues, which are not new to communities,” Irfan said.

“Tackling root causes is critical if we want philanthropy to be part of the solution and not the problem.”

Restructuring philanthropy for racial equity

Irfan said that beyond providing short-term and emergency funding, funders are still considering a medium or long-term response. She herself has committed to two deeper meetings on structural racism and Islamophobia, which have already had more than 50 funders attend.

Calls for additional, longer-term and stable funding commitments were also prevalent during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests.

The Funders for Race Equity Alliance wrote that “funders have a responsibility to redress the historic underinvestment” in racialized communities.

“This can be done by: ring-fencing funds, providing additional pre-application support, pooled funds, and re-granting through Black and Minority Ethnic intermediary organisations.”

Between 2021 and 2022, the Civic Power Fund analyzed funders’ commitments, particularly in response to Black Lives Matter.

“We were keen to understand whether this shift in funder discourse represented a shift in funder practice,” the organization wrote.

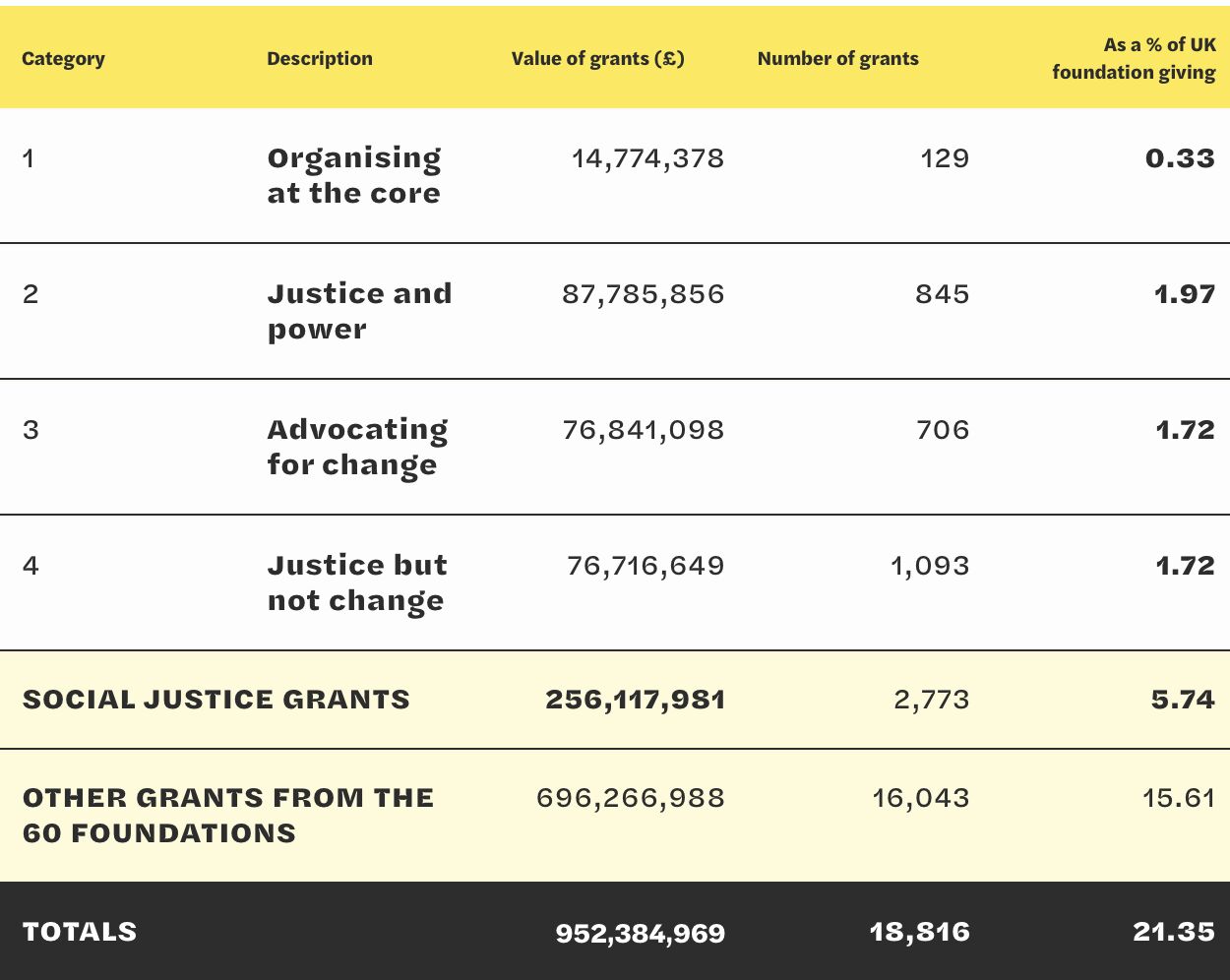

Having analyzed £950 million worth of grants, the organization’s Funding Justice 2 report found that 5.7 per cent of UK foundation giving went towards work to tackle injustice, while 0.33 per cent of foundation giving went towards “building people power through organising.”

Cooke also encouraged funders to “recognise the power that they hold” and use it to influence long-term policy and advocacy work that addresses the root causes of racism.

UnLtd, a foundation dedicated to social entrepreneurs, has been trying to centre those with lived experience as an effective source of knowledge, said Mark Norbury, chief executive.

Sixty-eight per cent of the foundation’s awardees identify as black, Asian, minority ethnic or disabled, he added.

But beyond just giving out funding, Norbury and his team are asking more fundamental questions.

“It’s not just about who gets the awards, it’s also how they are made: in terms of the scorecard of who does and doesn’t get an award, who sits on the decision-making panel, and who sits on the board.”

When the racist and Islamophobic riots surfaced over the summer, Norbury first checked in with the social entrepreneurs that UnLtd works with but also recognized that the foundation needs to hold itself accountable.

“There are particular communities where we need to challenge ourselves and ask: ‘why are we not getting so many applications from this community?’”

Data helps funders track systemic change

In order to hold themselves to account, UnLtd collects data to understand not just to whom the foundation is giving awards, but the overall picture of who they are getting applications from as well.

The foundation also collects data on how awardees feel about the support they receive from UnLtd, but does not yet collect data on how the grantees use that funding in the community.

UnLtd is currently piloting an impact measurement tool that “looks at both social value creation and beneficiary wellbeing,” Norbury said.

Funded by the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation and the National Lottery Community Fund, a group of UK funders came together to create a shared DEI Data Standard, a means to classify and measure the extent to which funders are channelling capital towards marginalized groups.

The Standard measures impact by tracking data of population groups, including communities experiencing racial inequity, people with disabilities, faith communities, the LGBTQ+ community, migrants, older people, children and young people, those who are economically disadvantaged, and women and girls.

The DEI Data Standard helps funders track the impact of who has participated in the projects they have funded, the missions of the organizations they have funded, and the board / leadership diversity of those organizations as well.

Although multiple funders have now implemented the DEI Data Standard, it has been difficult to get everybody on board, said Josh Cockcroft, co-chair of the DEI Data Group and data lead at the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation.

It depends largely on interpersonal relationships, and funders encouraging other funders to join.

Funders also display risk aversion in how they award grants, Cockcroft added.

“If you haven’t been funded by Esmee and you’re applying to us cold and uninvited, your success rate is about 1.5 per cent. If you apply to us and you’re invited, I think the success rate is around 70 per cent.”

For Irfan, who published a report on transformative philanthropy last year, it’s crucial that foundations operate with history in mind.

“The critical issues facing our communities are too important and the need too urgent, to continue to carry out philanthropy in an ad hoc approach,” she wrote.