Social impact professionals are on the verge of burnout — these organizations radically changed their work culture to help

Why It Matters

Canadian Mental Health Week provides an opportunity to practice values and restructure organizational goals, which can ultimately lead to increased performance and better outcomes. While some of these measures are unconventional in the non-profit sector, the stakes are high, as deteriorating mental health may lead to employee burnout.

This story is in partnership with Innoweave.

Last March, Cheyanne Lobo’s father was amongst thousands of Canadians who were stranded in India, unable to return to Canada as flights out of India were suspended.

“It was a very stressful period in my life,” says Lobo, the marketing coordinator at JAYU, an arts-based human rights charity. Lobo, who spent weeks strategizing with other family members on how to get her dad home, said she was able to better focus on this family emergency largely because she was only working four days a week.

Along with all other staff at JAYU, she’d shifted to a four-day work week in early 2020, before the pandemic hit — which further reinforced the need for a better work/life balance.

JAYU’s four-day work week is only one example of the ways social impact organizations have changed their practices to better support their employees through the pandemic. As many have struggled to cope with social isolation, employment instability, and repeated lockdowns, some organizations have recognized these challenges, opting to prioritize their teams’ wellness.

And while the stresses of the pandemic are widespread, Lobo believes the stress heightened for those who work in the non-profit sector. “In the non-profit industry… there is burnout but no one talks about it. There is an underlying sense of guilt that forces people to put the work first and themselves second,” says Lobo.

Biju Pappachan, the executive director of POV, a skills training non-profit, says that due to a lack of resources — which is common in non-profits — employees are expected to juggle multiple responsibilities.

“We’re already operating in ambiguity in the non-profit sector and the pandemic added to this. On top of that when you put in the lack of connection that occurred during the pandemic, it created the perfect storm,” he says. “If you’re not practicing self care, there are a lot of cases of burn out over the last year, including myself.”

Like Pappachan, other leaders in the non-profit space have experienced the same stress and burnout. Mike Prosserman, who runs EPIC xChange, peer support groups for seniors leaders and executive directors of non-profit organizations, says that when surveying leaders about their most pressing concern over the last year, mental health and wellness has ranked as the top issue. He says leading a non-profit during the pandemic, with limited or restricted funds, uncertainty, increased demand for services, and high expectations from boards inevitably leads to leaders feeling stressed, anxious, and experiencing other mental health issues.

“We’ve seen (non-profit leaders) have to take leaves and folks are at the end of their wick — and they’ve been at the end of their wick for the last six months. I’m quite concerned about some folks,” he says.

In EPIC xChange’s peer support groups, which consist of groups of 10 leaders of non-profits, charities, or social enterprises who meet regularly to discuss organizational challenges and support one another, Prosserman says it’s obvious that the pandemic has taken a toll on the mental health of those in the social impact sector..

“The word that was used most during the last session was ‘exhausted’ and the question was how do we motivate people who are burned out when we are also burned out ourselves?” He says being a non-profit leader is a seemingly “impossible job” during the pandemic. While non-profits scrambled to provide online services during the pandemic, Prosserman says some funders have been generous in permitting organizations to allocate funds where they need it most.

“But there still is this pressure to move your work online,” he says. “Ok, so (you receive) a $50,000 grant to move online -— that’s like starting a whole new organization during a pandemic. Not a lot of people appreciate how challenging that is.”

Providing benefits, flexible work hours, and wellness check-ins

During the pandemic, Pappachan, who leads POV, secured health benefits, through the Ontario Nonprofit Network, for the organization’s team members, ensuring that staff could access mental health professionals, such as therapists, and a 24/7 crisis support line.

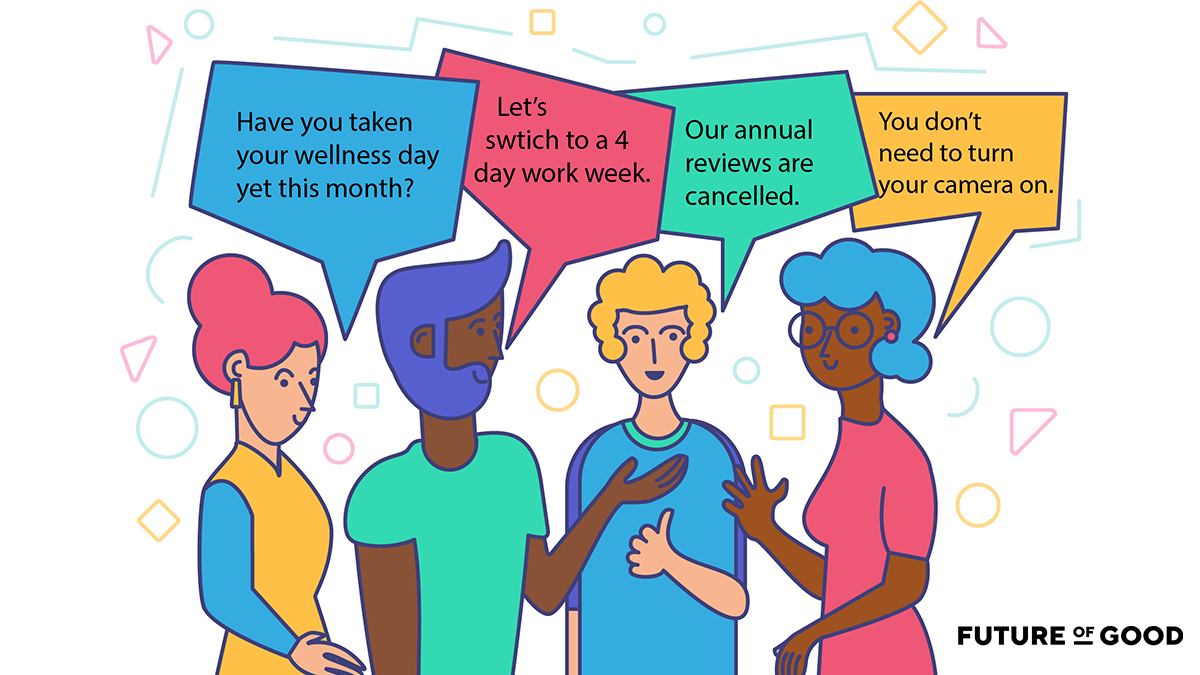

He also renamed the organization’s sick days to wellness days, which he says allows for people to take time off work without them being physically ill or at the point of burnout. “My operations lead tells them (the team), ‘You have this many wellness days left, maybe you should take one this month,’” Pappachan says.

He also renamed the organization’s sick days to wellness days, which he says allows for people to take time off work without them being physically ill or at the point of burnout.

He found that the team was working more hours from home than they would at the office, which led him to allow staff to determine their own work hours. Some start their day at 11 a.m. and work beyond 5 p.m., which he says signals that they’re managing self-care as they need. There’s also no expectation for employees to turn their cameras on during online meetings.

It’s these small changes that foster an environment that centres wellness, he says, and allows people to “show up how they want to show up without the pressure of what ‘professionalism’ looks like.”

Experimenting with a reduced work week

Prior to funding the arts and human rights charity JAYU, Gilad Cohen worked for multiple film festivals and a non-profit, where he says overworking was the norm. “I can’t tell you how often I’d hear folks, myself included, justify sleeping like three hours a night, eating poorly, not exercising, not seeing family for months on end,” Cohen says.

Over time, he began questioning the typical Monday to Friday, 40-hour work week structure, wondering if it was truly conducive to productivity, and found examples that proved otherwise.

In Japan, when Microsoft implemented a four day work week, it reported a 40 percent rise in productivity. Similar results have been duplicated in trials around the world. One international study found that half of workers reported they would be able to do their job in five hours or less per day.

“It’s clear that there is a direct correlation between working less hours in a week and being a happier, more balanced individual who is also more productive and energized at work,” Gilad says.

In January 2020, prior to the pandemic, Cohen spearheaded a year-long pilot of a four-day work week at JAYU, to see whether it would impact the team’s productivity and stress levels.

At the organization, work hours have been reduced from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Monday to Thursday. The team took a vote on when they felt they were most productive during the day. To test their theory, they did trials, starting at 9 a.m. on one week, 9:30 a.m. the next, and then 10:30 a.m., before settling on the current start time. If employees need extra time to work, they are encouraged to go no later than 5:30 p.m., meaning they work between 24 to 32 hours per week, while being paid for 40 hours.

Cohen says the year-long pilot, which wrapped up in January was an “overwhelming success,” and is now a permanent fixture at the organization. In a survey, 100 percent of JAYU staff says they have a better work/life balance, and 86 percent feel an improvement on their mental health. Previously, 77 percent of staff reported self-medicating during the work week, which is now down to 29 percent.

Meanwhile, JAYU raised more money last year than it ever has, and was able to grow their team, and expand their programming to serve more people. “I don’t want to lay all of this in the lap of the 4-day work week, but I owe a lot of it to the fact that staff are feeling more rested, they’re showing up to work more focused, and they’re getting more done,” Cohen says.

The four-day work week in practice

While some experts and practitioners tout the advantages of employees working reduced hours as it can improve productivity and outcomes, Lobo says this link is misguided.

“Conversations about a reduced work week… are centred around productivity and how much work employees are getting done in a (shorter) period of time — but to me, that’s less important than the sentiment of a four day work week. It’s about treating your employees like people,” says Lobo, reflecting on how it helped her through the time her father was in India.

Prior to the pandemic, JAYU had a policy of unlimited sick days and unlimited vacation time for team members. “I understand it’s a really radical position for an organization to take and you have to believe your employees won’t take advantage of it, but during the pandemic, it’s been really helpful and it’s been used by us a lot. You can take a mental health day — there are really no questions asked,” Lobo says.

While this culture of prioritizing wellness was in place prior to the pandemic, Lobo says the shift to a four-day work week created a “palpable difference,” explaining that the working environment and team dynamics are noticeably more positive. She says the team has been using a project management software as a shared gratitude journal, to uplift one another and share their appreciation of their colleagues.

Reevaluating organizational metrics and employee performance

When the pandemic hit, Biju Pappachan, the executive director of POV, knew the organization’s ability to follow through with its projected outcomes and donor expectations would be drastically hindered.

POV provides at-risk youth with technical training, skills, and experience to break into the media industry. As lockdowns impacted the ability to provide this training in person, Pappachan questioned what the organization would be able to achieve, and shared this concern with funders. “If your funding is contingent on successful outcomes, we will not be successful next year,’” Pappachan told them. “The funders said don’t worry about the outcomes, just deliver the services the best you can to the people you’re serving.”

While funders removed this “mental pressure” from POV’s team, Pappachan says, he adjusted the organization’s expectations of the team as well. Traditionally, all staff members participate in an annual performance review, which involves assessing the organization’s expected performance of an individual against their actual performance.

Early on in the pandemic, Pappachan told his team this would shift as he rethought the value of assessments at a time of heightened pressure, isolation, and limitations due to working from home. “Lets get rid of these quantitative metrics of success and shift towards a value-based and self-care based approach of what they think success looks like and whether they think they hit it by using their own assessments,” he says.

At POV, while employees still have goals and their performance is assessed, Pappachan says it’s self-governed. Employees report to their supervisors how they are working towards success, and what their plan is for managing their wellness, whether that means starting work in the afternoon or not checking their emails during the evenings.

Pappachan, who grew POV’s team from three to 10 people during the pandemic, has taken the lead on human resources during the last year, championing a culture change within the organization that caters to employee’s wellness needs. Now, the organization is bringing on a consultant to develop their human resources model and communications, in order to formalize it and ensure buy-in from the team and people the POV serves.

Prosserman says POV is one of several other organizations in the support group he runs changing how they do their annual performance reviews, but that even conducting a review at all can cause stress. “It’s almost insensitive to do performance reviews this far into the pandemic. What’s the baseline or benchmark that you’re comparing to?” he says. “It’s not helping now, because you should get an award for just surviving the pandemic.”