'Navigating a societal shift without any of the scaffolding': Remote frontline work, trauma and wellbeing

Why It Matters

We’ve explored the impact of digital services on community members, but there has been little investigation on the other side of the coin. Working in digital-first teams can provide flexibility and work-life balance, but in community services, it can also lead to feelings of isolation among staff.

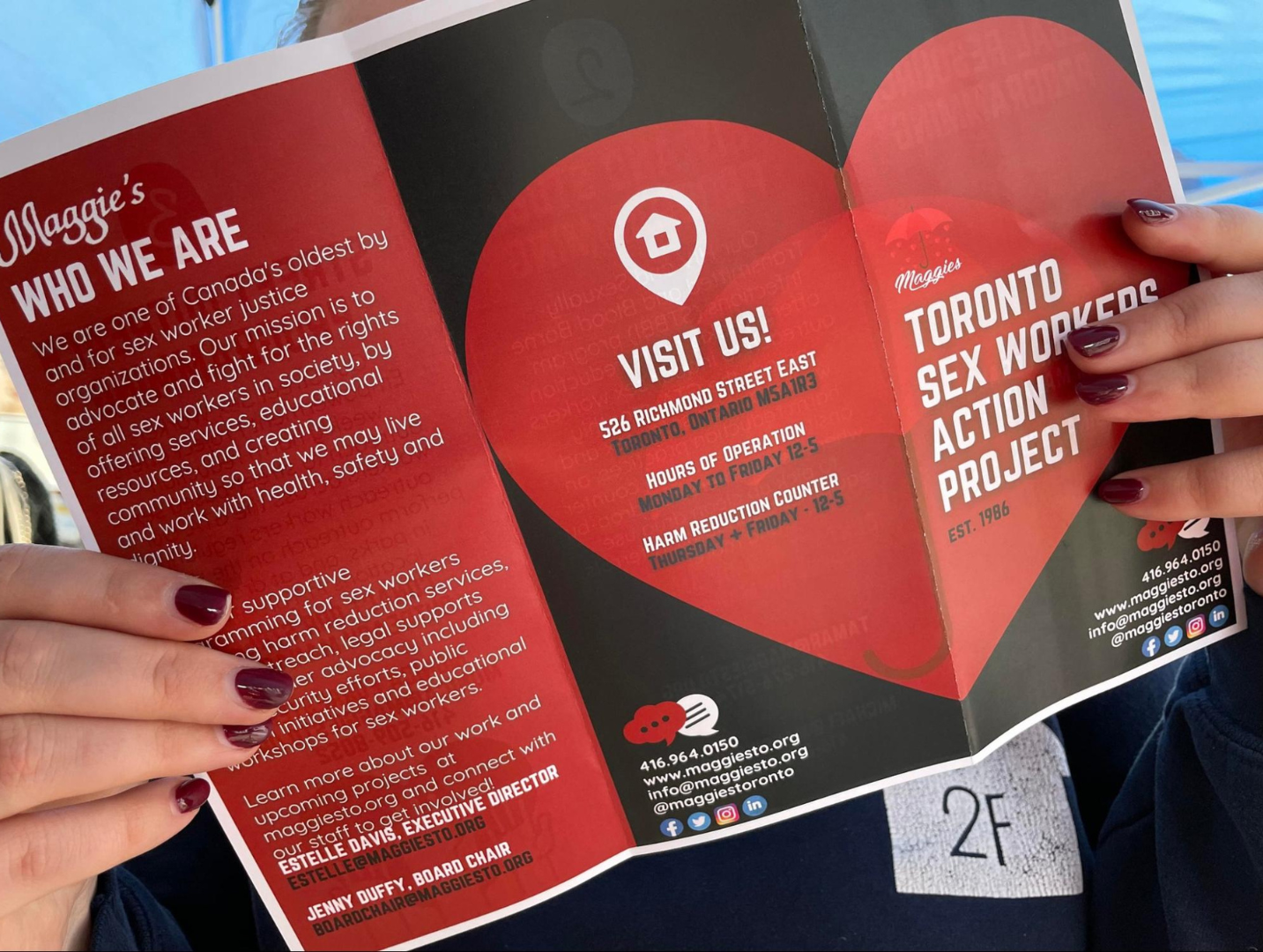

In late 2023, Maggie’s Toronto, a non-profit organization advocating for the rights and safety of sex workers, was consumed by a raging fire.

“It struck us so quickly,” said Executive Director Ellie Ade Kur.

“Within a span of hours, our entire two-storey workplace was gone.”

A flurry of emergency activities followed, from fire reports and police investigations to what they could salvage from the organization’s work. Immediate deliverables, of course, went out the window. As they scrambled between one emergency and another, Maggie’s team decided to step back and take two weeks off.

“We needed to have an opportunity to grieve,” Ade Kur said. After all, the fire destroyed the physical space where the team and its work had grown.

Now, as the Maggie’s team returns to provide critical support to sex workers in the Greater Toronto Area, Ade Kur estimates that around three-quarters of the organization’s work is taking place remotely. Before the fire, the team was already providing services remotely around 25 to 50 per cent of the time because of the pandemic.

How does remote service provision affect non-profit staff and frontline workers?

Services delivered remotely or digitally are becoming the norm for many social-purpose organizations. The pandemic might have been the initial catalyst, but the expectation that work would be “better” post-Covid hasn’t quite materialized, said Omar Yaqub of the Islamic Family & Social Services Association (IFSSA) in Edmonton.

“It’s akin to someone going through a bike accident,” he said. “The adrenaline is pumping, and you’re able to get up and move to safety. Once you get to safety and the adrenaline wears off, you’re now seeing that the bike isn’t rideable. Our frontline staff are now dealing with that adrenaline wearing off.”

At IFSSA, the proportion of remote frontline work depends on the service. For example, Yaqub said refugee sponsorship and counselling work occurs primarily remotely, whereas food security services are all carried out in person.

RELATED: Volunteer emergency responders in Nova Scotia to receive more mental health support

At 211 Ontario, while service provision has always been largely remote, the team sensed that callers were much more desperate during the pandemic. “When callers were trying to get through to government [agencies], the doctor’s office, schools or healthcare [facilities] and could not, they were calling 211 instead,” said Erin Modin, a team lead at 211 Ontario North, based out of Thunder Bay.

For lack of a better word, 211 navigators became “dumping grounds” for callers’ anger, frustration and devastation, she added.

It became challenging for staff not to feel like they were letting callers down if they couldn’t help or take many calls in a single day.

“We got a lot of things directed at us that wouldn’t have been directed at us under normal circumstances,” Modin said.

“We had to make sure we were not getting burnt out emotionally at the end of the shift every day, to get up and do it all again the next day.”

At this time, staff across 211 Ontario had been sent to work from home – three years later, they have still not fully returned to their offices.

“Our staff is trained to know what to do in case of an emergency, but not when it goes on for three years,” added Karen Milligan, executive director of 211 Ontario.

With most 211 staff in Ontario still taking crisis calls remotely, it has become challenging to support staff, troubleshoot, and answer questions they might have, said Annette Huizinga, who manages 211’s partnerships and networks. “In a remote environment, I’m relying on my staff to reach out to me,” she said.

Not only do staff need to feel comfortable enough to reach out for support, but many might also feel reluctant to leave a long queue of calls to seek that support.

There was a point at which Huizinga realized that working away from her team was a “long-term and possibly a permanent situation” that she’d have to make the best of.

How are non-profit leaders prioritizing care and wellbeing?

“There is a great deal of grief in the service provision aspect of our work,” Ade Kur said, adding that Maggie’s street outreach team is often dealing with situations that include drug overdoses and extreme violence.

“It feels important to weave grief processing into the benefits we offer to staff.”

Maggie’s has invested extensively in benefits for its staff, including adding funds to individuals’ healthcare spending accounts, introducing a four-day workweek, and encouraging staff to make full use of sick days without worrying about hitting every deliverable within a specific time frame.

Ade Kur wants to give staff “constant reassurance that it is OK to step back from this [work].”

The team is also trying to come together once every two weeks in a physical space, becoming more deliberate about how they use that time together.

“Losing our space as rapidly as we did provided us an opportunity to rebuild our programming,” Ade Kur said. She aims to work with staff – some of whom are also sex workers – to cover the costs of their return to a physical space.

At 211 Ontario, the leadership team engaged Dr Taslim Alani-Verjee, the director and founder of the Silm Centre for Mental Health in Toronto. The Silm Centre provided team leaders and executives with workshops and resources on burnout and vicarious trauma and offered counselling sessions to all staff.

As well as simple self-care reminders, like before and after-work transitions, going for walks, and drinking water, Dr Alani-Verjee’s sessions also aim to remind staff that they don’t have to feel the total weight of each caller’s difficulties.

The counselling services offered to 211 Ontario staff are now available to their family members. As well as individual counselling, staff can request couples or family counselling.

“We saw big usage in the early days when it was first offered, and then it trailed off,” Milligan said.

“There is then a little uptake when people are reminded [of the service].”

If remote frontline work is here to stay, how do we continue caring for staff?

Going forward, Ade Kur said she thinks Maggie’s will continue providing services in virtual and in-person environments. The team is currently fundraising to rebuild a dedicated space for sex workers in the Greater Toronto Area, as well as a workplace for staff to collaborate “when everyone is right down the hall.”

Yaqub, who accepts that remote service provision is here to stay, says that the sector is still “collectively navigating a societal shift without any of the scaffolding.” For him, physical spaces will always be meaningful and necessary.

“Community support is being present, but the reality of the way we work is that that is increasingly hard. We are physically distant and don’t have a circumstance that allows us to be together,” he said.

“Supportive systems require us to break bread together and share deep experiences with each other.”