‘We are waiting to see tangible results’: Five Black social impact leaders on the sector’s anti-racism progress

Why It Matters

Ending systemic racism will require more than just platitudes. Discrimination in the sector happens through badly designed funding agreements, poor HR practices, and deliberate exclusion — changing that will require leaders to take a hard look at their everyday practices.

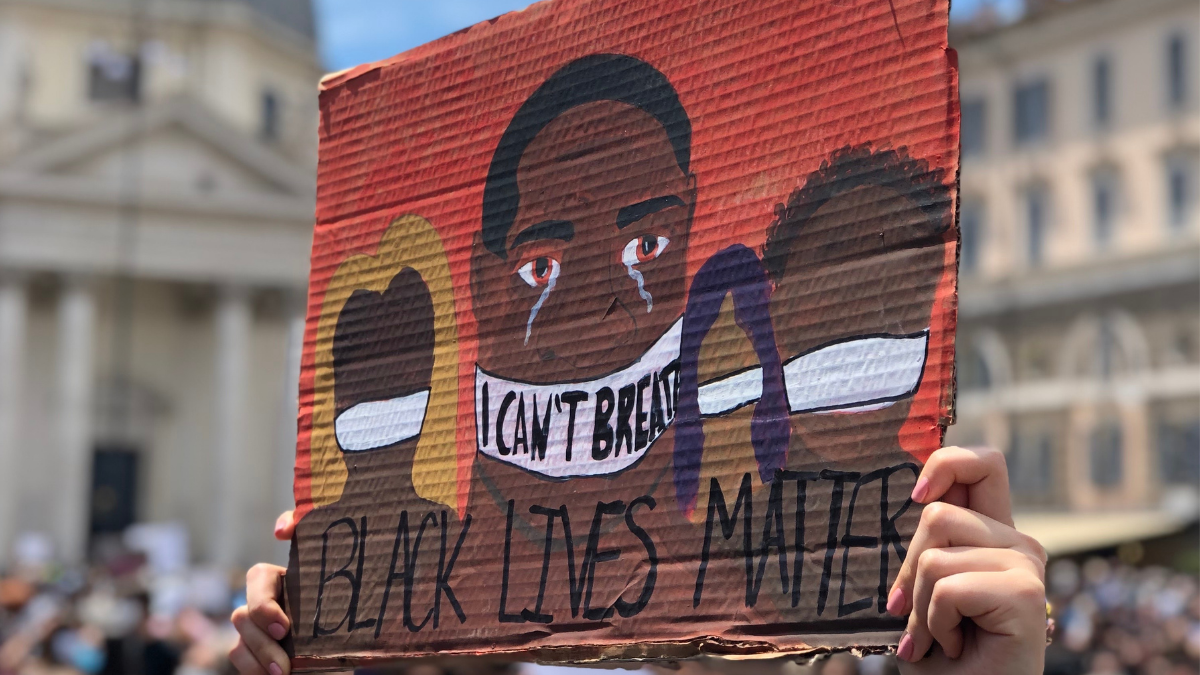

Nearly four weeks after George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer, over a dozen social impact leaders signed a public solidarity statement against racism that admitted Canada’s social innovation and social finance sectors had a lot of work to do.

“We must examine and concretely change our own leadership, our teams, internal policies and practices, discovering where we reinforce the old systems we’re aiming to uproot,” the statement says.

Among several promises are the development of anti-racism and anti-oppression training for all Investment Readiness Program (IRP) partners, the creation of a working group on inclusion for the social finance and social enterprise sectors, and work on a “self-determined” fund to get under-represented communities involved in Canada’s social finance and social enterprise sectors.

Tracking progress on these promises is difficult. It isn’t clear whether the fund or anti-oppression training for IRP partners was developed, but a solidarity working group on social finance, coordinated by Social Enterprise Through Social Inclusion (SETSI), did launch in 2020.

This solidarity statement was one of many offered by social impact organizations across Canada and the U.S. over the summer of 2020. Most promised to stand with the Black community against racism and hate, but rarely did any organizations provide regular updates on their progress. A year after Floyd’s murder, it is difficult to say if last summer’s surge in awareness of anti-Black racism within the sector will translate into long-term action.

Future of Good spoke to five Black leaders working in social impact and inclusion to ask about the progress made by Canada’s social impact sector on anti-racist action since 2020:

Organizations still need to create inclusive working environments.

Last summer, as Black Lives Matter demonstrators took to the streets around the globe, Kassandra Kernisan, executive director of DESTA Black Youth Network, had to hire its first digital community manager to handle an overwhelming surge in social media traffic. Dozens of organizations approached DESTA with offers to volunteer, donate, or for help including more Black youth in their workforce, which Kernisan says is great.

But she says organizations also need to create more inclusive, accommodating office environments for their employees. A combination of insensitive comments, microaggressions, and simply a lack of understanding from management of a marginalized worker’s experience can be very damaging to new hires. Kernisan says companies are slower to build more accommodating environments because it requires time and investment. “It’s one thing to have diversity within your workforce, but then is your space an inclusive space?” she says. “That’s just a lot of work.”

There still aren’t enough Black leaders in the social impact sector

Representation within Canada’s social impact sector remains a major problem even after a year of anti-racist action, equity conferences, and pledges from sector leaders. “Too many organizations remain predominantly white led, despite the fact that we are disproportionately affected by the issues that these organizations are working on,” writes Paul Taylor, executive director of FoodShare Toronto, in an email to Future of Good.

He says the social impact sector should be “bolder and braver” in supporting calls for justice, sovereignty, and liberation from Black and Indigenous communities. “The social impact sector should be challenging not just the ways in which white supremacy manifests itself in organizations, but also in society at large,” Taylor writes. And Black social impact professionals shouldn’t stand alone in these efforts. “Black leaders in the sector are constantly asked to comment and reflect on white supremacy and racism,” he writes, “while many white leaders continue to perpetuate both and remain unquestioned and unaccountable.”

Anti-racist pledges aren’t enough

As Canada’s social impact sector begins to reckon with its history of inequity towards Black communities, Rebecca Darwent, working group member of the Foundation for Black Communities, says it is prone to viewing incremental change as progress, yet Black communities in Canada still aren’t treated in an equitable manner. “Statements, speeches, committees, and task forces have sprung up in the wake of racial reckoning and we are waiting to see tangible results,” she wrote in an email to Future of Good.

The findings of the Unfunded report — that Black-led or primarily Black-serving organizations get pennies for every $100 in grants disbursed by Canadian grantmakers — appeared to galvanize the social impact sector. But shock and dismay over its findings, and the accompanying declarations that the social impact sector can do better, is not good enough. “We must see accompanied action that increases Black staff, board members, advisors and sets the stage for Black communities to share in power, decision making and be self-determined,” Darwent wrote.

Give us data on the sector’s progress towards racial equity

Sharon Nyangweso, CEO and founder of QuakeLab, a communications and inclusion agency, says the sector is hinged on decades of historial inequities, especially around access to funding and care. Fixing that won’t happen overnight. “The reality is, there’s not going to be any meaningful change within the span of a year,” Nyangweso says. This is especially true when institutions or industries try to work within existing ( and problematic) systems to correct the very damage they caused in the first place.

Ultimately, Nyangweso says, many solidarity statements released last year by organizations offered no concrete data on their own inequities — or benchmarks for progress. “I would love it if these organizations came out with data from the last year to give us an understanding: Where are we? What needs to happen? Where are the really consistent patterns that we are seeing?” she says. Then, Nyangweso adds, she’d love to see a straightforward acknowledgement of the problems within an organization’s specific policies. “I’d love to see that really clear line of thinking that we see from these organizations for literally everything else,” she says.

Funders need to adapt their models to fit Black-led organizations

Over the past year, Titi Tijani, the president of African Communities of Manitoba Inc, says the federal government has announced more funding for Black communities across Canada, but the process of funding programming, rather than supporting organizations through operational grants, remains the same. “They talk the talk, but when you get into the nitty gritty of discussion, we are back to the same old system — trying to assess you the same way they assess regular organizations that are not Black led and forgetting that those organizations have the structures already, whereas Black-led organizations do not,” she says.

Many Black-led organizations simply don’t have any operational funding. They rely entirely on volunteers who work full-time day jobs elsewhere. More program funding may be available through the federal government, but Tijani says the organizations most in need of it simply don’t have the staff or resources to run the sort of programming they want. “So more funding for the Black [impact] sector is announced, but the process has not changed,” Tijani says. “Those monies are tied up in politics and they’re not accessible to communities that need it. That is the issue.”