Some Canadian charities reeling from insurance premiums doubling over past five years

Why It Matters

Insurance isn’t a sexy expense. When premiums or deductibles rise, non-profits often struggle to find funders to take on these additional costs. Without additional revenue, some cut back on other expenses or pass costs along to others further down the charitable food chain.

It’s not an easy time to run a church.

For years, donations have declined, and the ranks of volunteers have thinned. But increasingly, faith institutions are also contending with rising insurance costs.

This year, Montreal’s St. Jax Church will pay $49,500 for insurance — up more than 40 per cent over the last three years.

“These are massive, massive increases — well beyond the rate of inflation,” said Graham Singh, the church’s senior pastor.

To cover the increased cost, the church is passing the expense along to its tenants — a refugee resettlement organization, a non-profit circus, and an Indigenous-led homelessness outreach team, among others.

“Nobody wants to do it, but you also don’t want to close the building,” he said.

Though their situation is challenging, St. Jax isn’t alone.

Many organizations nationwide that own aging or heritage properties have faced considerable premium increases for property or general liability insurance in recent years.

A 2022 survey conducted by the National Trust For Canada of more than 750 heritage property owners, including non-profits, found seven per cent of respondents’ premiums had more than doubled over the previous five years.

Eight per cent reported premium increases of 50-100 per cent, and 27 per cent saw increases of 20-50 per cent. (Just two per cent reported lower premiums.)

Some charities without aging properties have also seen increases.

In a 2022 survey of BC music festivals, including for-profit and charitable providers, 40 per cent reported premium increases of more than 16 per cent in the past year, according to BC Music Festival Collective executive director Deb Beaton-Smith.

Country-wide, about 30 per cent of non-profits are concerned about rising insurance costs over the next three months, according to data from the federal Canadian Survey of Business Conditions.

Insurance experts are cautious about drawing links between individual organizations’ experiences in different charitable sub-sectors nationwide.

The premiums and deductibles offered to any organization are based on various factors — previous claims history, the amount of coverage desired, risk factors specific to each organization’s work and more.

Still, they say the insurance industry faces stiff headwinds due to rising climate-related payouts, inflation and other factors, causing some insurers to pull back on issuing policies in perceived higher-risk markets and higher premiums and deductibles.

But others suggest insurers aren’t entirely blameless — that some misunderstand the risks associated with insuring heritage properties and are using the cover of tough macroeconomic conditions to drive profits.

Macroeconomic troubles

Experts say about half a dozen factors contribute to more risk aversion among insurers. At the top of the list is climate change.

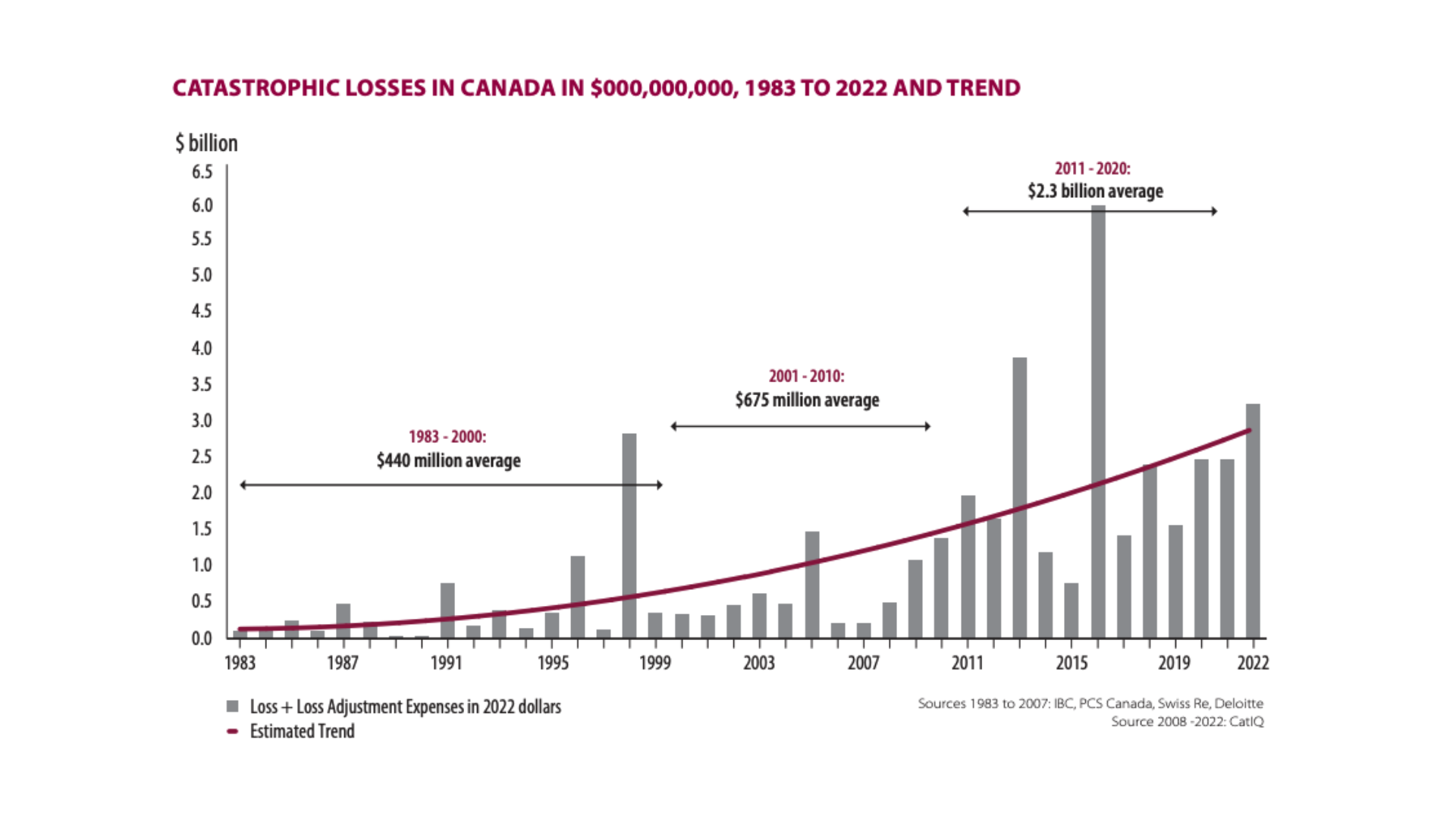

Over the last two decades, the number of so-called catastrophic losses costing insurers over $30 million has increased dramatically because of more frequent climate-related extreme weather events.

Last year, severe weather-related losses caused $3.4 billion in damage — the third worst year for insured losses in Canadian history, according to the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC).

With payouts projected to rise further, some insurers raise premiums to ensure they can meet their obligations when disaster strikes, said Rob de Pruis, IBC’s national director.

In addition to climate pressure, inflation is also impacting the industry.

Over the past five years, the cost to rebuild a commercial property has increased about 40 per cent, according to Statistics Canada’s building construction price index, due to increased building and labour costs.

This, too, forces some insurance companies to raise rates to ensure they can support customers to rebuild in the event of a disaster, said Colin Robertson, chief underwriting officer for Ecclesiastical Insurance, which provides coverage to charitable sector clients.

Current supply chain disruptions and a shortage of skilled labour also contribute to rising costs, he said. In this climate, rebuilding takes longer, and finding the right workers can be more expensive.

The industry is also facing higher so-called reinsurance expenses, said de Pruis.

Insurance companies purchase their own insurance from reinsurance companies to ensure they have the funds to cover their liabilities when catastrophic losses happen. With more extreme weather events, reinsurance is priced higher, driving costs up for customers.

All these factors contribute to a so-called hard market, said Roberston.

Under these conditions, some general insurance companies are more wary of providing insurance to charities or clients with heritage properties, reducing a charity’s options.

But while organizations understand these challenges, some wonder whether insurers are avoiding insuring some charities based on a misunderstanding of the risks — and taking advantage of the macroeconomic challenges to reap higher profits.

Joy Barrett, executive director of Castlegar Sculpturewalk, a BC-based, public arts non-profit that’s seen its deductible increase fourfold this year, said it’s not clear whether cost increases are based on legitimate industry pressures — or, like grocery stores, where companies are using the challenging moment as a chance to make “record profit.”

Heritage concerns and profit

In 1914, the Local Council of Women Halifax took possession of a beautiful heritage home in the city’s south end, replete with stained-glass windows, high ceilings and wood floors.

The donated property is now a lively community hub, with events and rented office space for many smaller community organizations that support women and gender-diverse people.

The trouble is, it’s not easy to insure.

Over the years, the number of insurers willing to cover them has dwindled, and the cost of their policy has steadily increased — despite having made no claims in over eight years, said Sarah MacDonald, president of the non-profit’s board.

This year, they’re paying about $7,000 in insurance — more than 10 per cent of the organization’s annual budget. The premium nets them a policy with $300,000 in coverage, which wouldn’t cover the cost of a complete rebuild, she said.

As a fundraiser, MacDonald knows donors aren’t interested in covering higher insurance costs, so instead, they pass the growing expense along to their tenants.

Part of the challenge non-profits face in obtaining affordable insurance stems from insurers’ misunderstanding of heritage properties, said Emma Lang, executive director of Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia.

Many assume that if a property were destroyed, it’d be necessary to rebuild it exactly as it had been before — but that’s not possible nor required.

“You’re not going to go and revive a dead medieval stained glass artist to do the job,” she said. “No one is expecting you to go in with your axe in the woods and find the tree that was born around the time of Colombus. That’s totally insane.”

Heritage associations have these conversations with insurance companies but don’t often get favourable responses. This can be particularly challenging at a time when the market is tight.

When a company determines which sectors to work within, they look at existing staff expertise, modelling of historic losses, and whether they think they can offer a winning value proposition, said Sean Kavanagh-Lang, a senior vice president with Aon, a large brokerage.

“As with any business, insurance companies are closely looking at [the] profitability of the products they [offer] to determine the best place to allocate capital and future investments.”

Yet beyond challenges facing charities with aging or heritage property, research from the Centre for the Centre for Future Work also suggests some charities may be impacted by higher premiums at the expense of elevated insurance industry profits.

In a 2022 paper, economist Jim Stanford found the industry’s profits jumped $4.8 billion between 2019 and 2022. (The study compared 2019 financial results to a 12-month period covering the fourth quarter of 2021 and the first three quarters of 2022.)

With this banner financial success, the insurance industry was one of 15 “super-profitable” industries whose price increases Stanford accused of driving inflation.

Extending the time period further, Canada’s 200-odd insurance companies earned an average profit of nine per cent between 2016-2022, according to the Insurance Bureau of Canada.

Asked about IBC’s figure, Robertson said insurance companies don’t always make a profit and must maintain their capital strength and solvency to protect customers.

“I understand it’s challenging, but I think when a disaster strikes and a property burns down, or you have a large liability claim presented to you, I think that’s when you really benefit from insurance. That’s when you want the insurance company to be there, stand behind you, and get you back up on your feet again,” he said.

Alternatives to existing insurance providers

With increasing difficulty securing affordable insurance, some charities are exploring alternatives.

Last year, the United Church of Canada launched a new program through which a UCC-affiliated company provides property and liability insurance to congregations, cutting out most of the industry-standard commissions and the profit motive, said Erik Mathiesen, United Church of Canada’s chief financial officer.

About half of United Church congregations have signed up, and many have seen significant savings. A $3 million investment in the program has helped net congregations $1 million in savings per year so far, Mathiesen said — a “staggeringly good result.”

Aside from so-called captive insurance initiatives, other charitable organizations are looking to their city governments for support.

Faced with heightened deductibles, Barrett said Castlegar Sculpturewalk has asked the local municipality to take on liability for their sculptures but has not yet received a firm answer.

Charities good for community stability: Singh

Though St. Jax has struggled with rising premiums, Singh says the sector needs to be cautious about demonizing insurance companies over increasing costs.

Their provider, Ecclesiastical, has been supportive of the church and others like it across the region and has strong connections to the charitable sector, he said. (A charitable trust owns the company, redistributing all profits to charity.)

Additionally, there’s a power asymmetry regarding charities and insurance providers. “We need them,” Singh said. “Do they need us? Not so much.”

The charitable sector must make a compelling case to insurers that social services create more resilient communities and cities, reducing risk overall, he said.

In addition, charities must speak the “love language” of insurers.

“We have to realize this is a very unemotional, very calculated party of our economy. We can criticize it, but we also need to learn how it works.”