Standardizing data collection could help non-profits fill gaps in critical community services. What’s holding them back?

Why It Matters

Non-profits often create ad hoc policies for managing, storing and sharing data, but they don’t always fulfill legal obligations or allow for the full utilization of important information. Standardizing how data is handled helps ensure vulnerable people don’t fall through the cracks and creates new opportunities for collaboration.

This independent journalism on data, digital transformation and technology for social impact is made possible by the Future of Good editorial fellowship on digital transformation, supported by Mastercard Changeworks™. Read our editorial ethics and standards here.

TORONTO / TREATY 13 – It’s a free service with the power to connect Ontarians in distress with localized information, on everything from disability supports, to crisis housing, child care and legal assistance in 150 languages. All they have to do is dial 211.

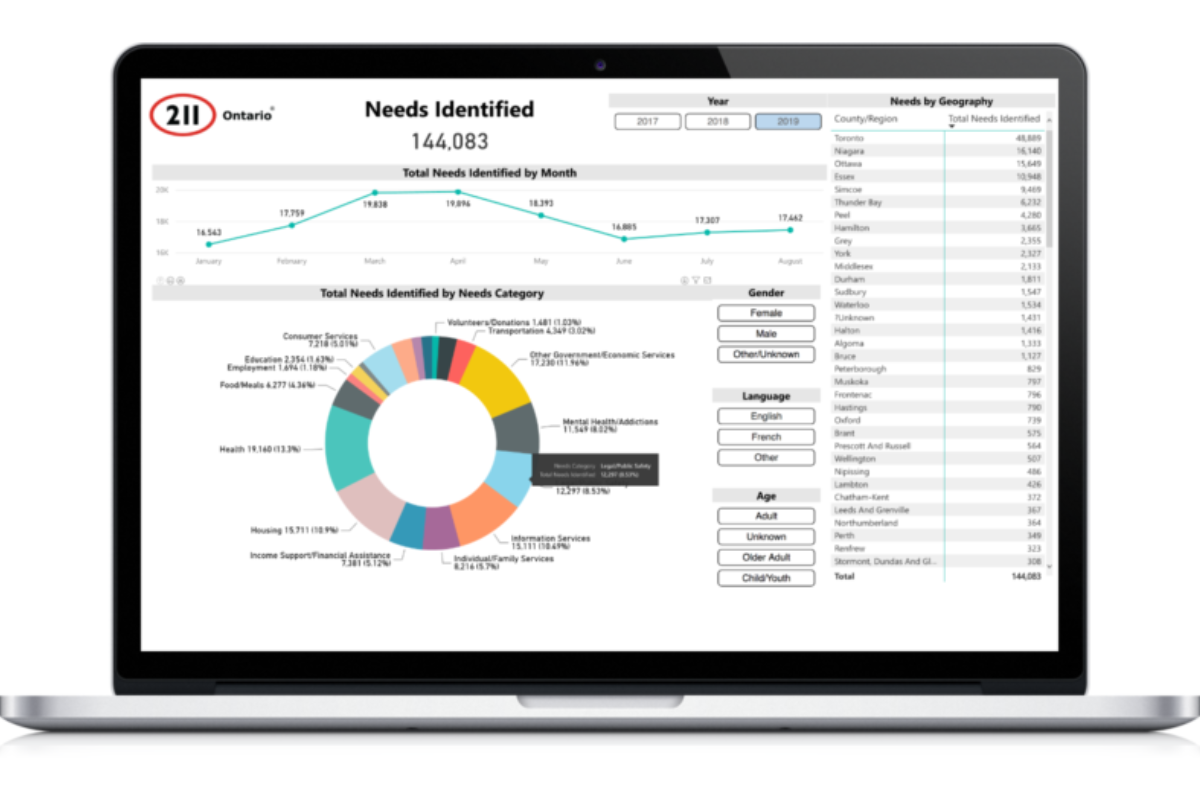

But maintaining a database of 60,000 ever-evolving community organizations, government resources and non-profits is a challenge, particularly when data collection and storage isn’t uniform across the province. “There isn’t a lot of integration in the way that services are delivered,” says Karen Milligan, 211’s executive director. “Unless we can get to a greater level of standardization, we can’t be interoperable.”

Multiple service providers feed data into this province-wide resource, but all organizations use different methods and criteria in the process, which can make matching a caller with the right resource challenging, Milligan says. Different provincial helplines affiliated with 211 also collect information in slightly different ways, she adds.

“Some are collecting an exact date-of-birth [from clients], whereas others are collecting age ranges. Some are collecting race-based data and some people are not,” she says. “We struggle with that consistency piece.”

But there are ways to make this system, and others like it, more efficient.

The Digital Governance Standards Institute or DGSI, in partnership with the Ontario Nonprofit Network (ONN), is working to develop a data governance standard for community and human services, a document also known as the CAN/DGSI 100-11. Once complete, this resource will help organizations like 211 better manage and protect their data, as well as comply with various regulatory obligations.

When the Digital Governance Council’s precursor organization — the CIO Strategy Council — held consultations last year, Milligan jumped at the opportunity to help shape new standards for data management, storage, sharing and governance in the social purpose sector. Those consultations resulted in a draft proposal for national data standards highlighting the barriers faced by the community and human service organizations, including uncertainty around regulatory requirements, a lack of consensus on tools and processes, and a continued reliance on paper documents and password-protected Excel files.

“If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there. This is where a standard can be very helpful,” says Katie Gibson, who led last year’s consultations and currently serves as the executive director of the Canadian Centre for Nonprofit Digital Resilience (CCNDR). “They give everyone a shared target to aim for. They tell us, ‘This is what good looks like.’ DGSI’s standards become national standards of Canada, which gives them some weight that other consensus-based frameworks may lack.”

Well-managed data increases program quality

Poor data governance has far-reaching consequences in the non-profit sector, which often collects data on vulnerable individuals. Improper management of sensitive, personal information can expose clients to further harm, such as fraud or identity theft.

Many charities and non-profits also collect and store their donors’ financial information, which if compromised, risks both the donor’s financial security and an organization’s reputation as a ‘safe’ place to donate.

The introduction of this standard aims to “provide a comprehensive framework that promotes responsible, ethical and privacy-preserving data collection, storage, use and sharing within the sector,” writes DGSI staff in a LinkedIn announcement.

“By mitigating risks such as unauthorized data usage, protecting donor information, preserving reputation, and ensuring the security of vulnerable populations, the new standard will empower service providers to navigate privacy and security challenges effectively.”

Darryl Kingston, the institute’s executive director, says the new standard has the potential to protect non-profits and their clients from risks associated with mismanaged data, while also opening up opportunities for innovation. A standardized approach to collecting and storing data will ease the process of sharing data across organizations – for vulnerable clients accessing critical social or community services, it means that their experience of moving between agencies can be much more seamless.

“People need us to connect the dots [between services], not for them to have to do it themselves,” Milligan says. “This conversation around data [governance] standards is a necessary ingredient to get to the next stage of service delivery, where we are integrating that experience on behalf of clients, who would no longer need to go through 25 separate intake processes, or get lost in the cracks between two agencies.”

Sharing data can also uncover underlying systemic issues facing communities, says Neemarie Alam, data strategy manager at the Ontario Nonprofit Network. If certain organizations, regardless of their size or subsector, can agree on ways to collect, present and share information, there is opportunity to better understand complex and interlinking factors that might be contributing to systemic inequality.

While improving client outcomes through data sharing isn’t a new concept, Milligan says the Canadian non-profit sector has only recently embraced the approach. For instance, in San Diego, a local ‘community information exchange’ saw health and social service organizations sharing data in order to collaboratively meet the needs of vulnerable people in the city. Ten years in, the city is now able to tangibly demonstrate the positive outcomes of a shared data approach, she says.

Non-profits invited to shape data governance standard

Although at the very beginning of the standard’s development journey, DGSI and ONN are seeking non-profit leaders and staff to participate in the consultation process as the standard takes shape. There are a couple of ways non-profits can engage in the process, firstly by being part of the Technical Committee that provides input during the standard’s drafting stage. They can also give feedback when the standard is fully drafted and published for a 60-day public review, where all feedback will be passed back to the Technical Committee.

From beginning to end, standards usually take a year to develop. “Standards development is an open and transparent process,” Kingston says.

“Multi-stakeholder participation means that no one individual, organization or stakeholder category can dominate the discussion. It ensures we’re following a certain process and that everyone with an interest can easily get involved.”

Gibson says non-profit leaders expressed a desire for clear direction on data protection during last year’s consultations. Non-profits and other stakeholders pointed out four key benefits of a consensus-based framework: avoiding duplicative efforts of each organization defining their own data governance policies; improving quality and protection of data, and reducing overcollection of it too; safe and secure data sharing and aggregation; and finally, increasing trust and consent among clients.

There was also a feeling that a common standard would particularly benefit smaller non-profits, who may not have the resources, expertise, or staff time to develop bespoke data governance policies. Gibson adds: “It’s more powerful and more efficient for everyone to work together than for each individual organization to spend their limited resources on developing their own policy from scratch.”

What holds non-profits back from robust data management?

A diverse range of non-profits, from a number of sub sectors, have already applied to participate in the Technical Committee, Alam says. There has also been a wide range of people in different roles in their respective organizations who want to participate. However, “there is still a lot of fear and hesitation,” Alam says. “We’re in the process of demystifying standards. They’re not the monster under your bed.”

When recruiting people to be part of the Technical Committee, Alam specifically points out that they don’t need to be a deep data or technical expert, which brings staff with more diverse and varied roles to the table. It also allows staff to appreciate that data collection, analysis and management can be the responsibility of anyone in a non-profit organization, particularly if there isn’t a specifically allocated data management role.

“A lot of communications I’ve sent out have stated that it is okay if you’ve never been part of a Technical Committee,” Alam says. “You just need to have some sort of familiarity with how data works in the [non-profit] sector.”

Participants in last year’s consultations also noted a standard could exacerbate certain administrative challenges facing non-profits. “Additional requirements for data governance without additional funding could increase burdens on staff and management, and leave smaller organizations further behind,” the Digital Governance Council pointed out.

There were also concerns about the specific content of the standard: would it be broad enough to apply to everybody, while still offering specific direction? Would the requirements laid out in the standard be compatible with software and hardware that non-profits use, as well as existing principles around Indigenous data sovereignty and community data ownership? Would it be compliant with funder requirements?

Funder requirements can have a substantial impact on the extent to which non-profits are able to engage with a standard. Standards are often developed through the lens of what a funder might want, Alam says.

“The DGSI allows for a shift in thinking about standards as support mechanisms, rather than an [additional] administrative burden.”

And while funders might, in principle, be in support of non-profits developing better data governance processes, they also need to take action and release capital in a way that allows non-profits to meaningfully participate in the development process. “The sector is struggling with [technology and] data infrastructure,” Milligan says. “It’s not something that is in funding envelopes, and smaller non-profits have struggled to get in line with any sort of standard.”

“Part of it revolves around the fact that we aren’t funded to build data scientists into our organizations,” she adds. “Non-profits get project-based funding, and are asked to make sure that less than 10 per cent of it is admin cost.”

Milligan also feels that relationships with funders can lead to a chicken-and-egg situation. Without funding to support administrative work, smaller non-profits are unlikely to be able to participate in the consultation and drafting process at all, and without them being present at the table, it’s more challenging to build a data governance standard that takes their capacity and resources into account.

“There may need to be a different approach with smaller non-profits, who may not have the capacity to be at the table,” she says. “How could a group like ONN coordinate focus groups for really small non-profits?”