The B.C. pilot project that prevents affordable housing loss

Why It Matters

Between 2016 and 2021, B.C. lost nearly 100,000 rental units priced below $1,000 monthly. For every new affordable rental home built in B.C., four more are lost to investors, conversions, demolition and rent increases, and new affordable units do not compensate for the loss of existing ones. The situation is similar in every Canadian province.

It’s been 11 years since the Brightside Community Homes Foundation has been able to buy a new property.

This winter, thanks to a strategy the CEO said he had never used to stand out in a real estate transaction, they were successful.

“I wrote a personal letter to the owners about our organization and its mission,” said William Azaroff, and the letter appears to have paid off.

This winter, the B.C. non-profit added Casa Mia to its $250 million portfolio of 26 properties. The three-story building, located on a quiet residential street in Burnaby 20 minutes from downtown Vancouver, has easy access to Edmond Park, the Tommy Douglas Community Centre, and the nearby public library.

There were nine bidders for the 56-unit complex built in 1967, but Brightside was the winner.

Creative strategy leads to more affordable housing

Brightside owns and operates affordable homes for Vancouver seniors, families and independent people with disabilities.

Casa Mia residents pay 40 per cent less than the average rental market price.

“It is a 57-year-old building. Most residents have lived here for decades, so their rents never skyrocketed like when there is tenant turnover,” said Azaroff.

Some rents are as low as $500 a month as rents are geared to income. Annually, renters present their income tax forms to Brightside, which ensures no one pays more than 30 per cent of their revenue for housing, andents fluctuate depending on the resident’s situation.

“If Casa Mia had been sold to a private owner, the rents would have had to be raised significantly to cover the mortgage,” said Azaroff.

Brightside’s values and relationship with its residents were detailed in the CEO’s letter to the owner, and they were added to the proposal. Azaloff also mentioned that Brighstside’s acquisition would benefit from financing from the B.C. Rental Protection Fund.

The province of B.C. announced the new fund in January of 2023. The $500 million initiative helps non-profits buy buildings with lower-than-market value rents.

Brightside paid $16.4 million to acquire Casa Mia 65 per cent of the amount came from the fund.

“We needed that much equity to keep the rents below market price,” said Azaroff.

“This 65 per cent is the gap between the revenue Casa Mia generates from the rents and the building’s market value.”

A decade ago, when Brightside bought a new property, the rental income would cover the acquisition cost, said Azaroff, “and we had a bit of surplus to cover maintenance costs.

“Today, if you pay $16.4 million for this building, you’ll need those long-tenured residents gone to double or triple the rents and cover your costs,” he said.

“I will never know if we were the highest bidder or if my letter to the owner made a difference, but I like to think that the family owning Casa Mia for decades cared about their tenants and chose us because we will maintain affordability.

“The fund might encourage other owners selling their affordable units to consider non-profits and co-operatives, as long as they get the market price.”

The problem the Rental Protection Fund is addressing

The 70 Casa Mia residents were lucky their rent is now protected. But for many low and medium-income renters, housing is a source of financial anxiety, not knowing if or when an owner will sell.

When the property owner does sell, they may end up having to move, which usually means a much higher rent and financial hardship.

Between 2016 and 2021, B.C. lost nearly 100,000 units renting below $1,000 monthly.

“For every new affordable rental home built in B.C., four more are lost to investors, conversions, demolition and rent increases,” said Katie Maslechko, CEO of the Rental Protection Fund.

“This loss is preventing British Columbia from keeping pace with the demand for affordable housing supply serving current and future residents.”

This situation can be seen in every province, she said.

“We all need to plug the hole in the bottom of the ship if we’re going to stand a chance of staying afloat, let alone make a net positive progress in terms of the overall supply meeting the needs of Canadians.”

In a nutshell, the most affordable housing is the housing that cities already have.

How we got into this mess

“In the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, B.C. built a lot of market rentals,” said Jill Atkey, CEO of B.C. Non-Profit Housing Association and Rental Protection Fund board member.

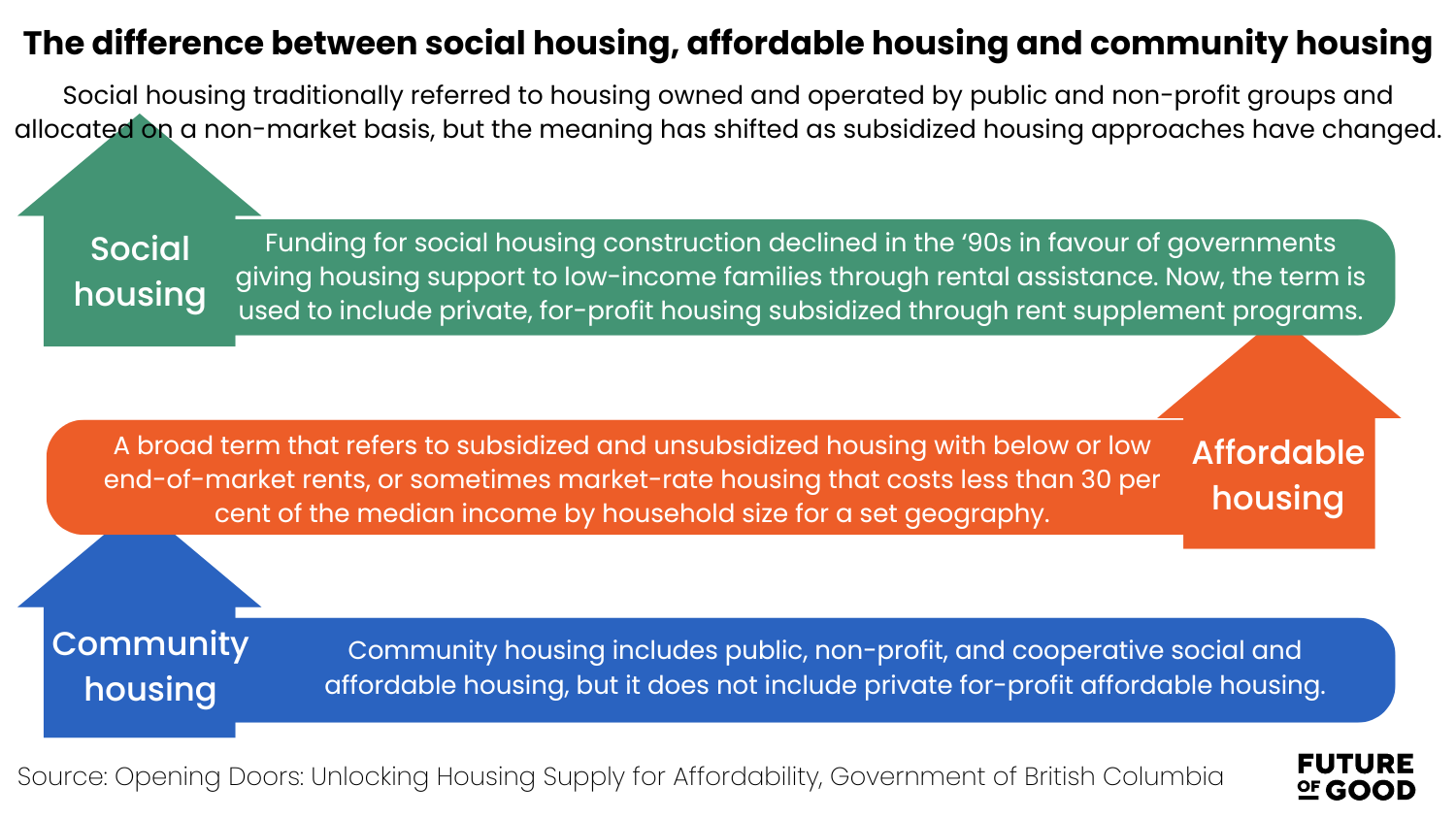

“Tax incentives encouraged the private sector to build those rentals. However, these incentives disappeared in the 1980s. And, in the early 1990s, the federal stopped funding affordable housing,” said Atkey.

So, from the early 1980s to 2015, B.C. did not build any rental housing. At the same time, its population grew significantly, and the housing prices took off.

“It meant that people were staying in rentals longer. So, the supply crisis became very real as more people sought rental housing,” said Atkey.

This exponential demand put pressure on existing units, driving up rents. At the same time, rental units were lost to conversion to condos.

“Even the best-intentioned private owners have no choice but to raise the rents when they acquire rental units. The acquisition price is so disproportionate that existing rents do not generate sufficient revenues,” she said.

Many Canadian cities that lost their grip on a low-vacancy market have found some solutions.

Rent supplements, for instance, help low-income households find shelter in the private market.

However, rent supplements are less effective in markets where low vacancy rates allow landlords to bid up rents rather than compete for tenants.

In those markets, rental supplements either cost more or do not go as far in helping the households they target.

Where the idea for the Rental Housing Fund originates

The community housing sector has advocated for years for the need for government financing to stop the erosion of affordable rental homes, said Maslechko.

In September 2019, the governments of Canada and B.C. established the Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability.

The group was tasked with examining housing trends for rentals and home ownership and then developing actionable recommendations to help British Columbians access housing that they can afford and meets their needs.

“We quickly concluded that new supply is essential in solving the affordability crisis,” said Atkey, who sat on the panel.

“But equally critical is protecting the existing supply from the erosion of affordability we’re seeing in market rentals. Without measures to stop that erosion, we’ll never build enough supply to meet the need,” she said.

Throughout 2020 and early 2021, the panel met with the public, experts and stakeholders.

Their report was published in 2021 and identified four affordability challenges.

The four affordability challenges

- Affordable rental units are disappearing faster than they are being built. Unless measures are taken to stem the loss of existing affordable rentals, it will be nearly impossible to address the need for affordable units through new supply alone.

- There are more people in need of community housing than there are homes available. All Canadian cities have wait lists of applicants for community housing. This share of unmet housing demand is attributable to multiple factors, including a mismatch between unit types required and unit types available, processing or eligibility issues and, crucially, housing prices that reflect induced scarcity rather than the simple cost of building homes.

- Demand-side supports, like rent supplements, are less effective in supply-constrained housing markets.

- Building below the market rate, especially deeply affordable homes, is not economically viable. Below-market-rate housing is typically not feasible as a for-profit venture, requiring public, private or charitable contributions to support its viability.

“Non-profit providers usually need to pay the same market prices for land and face the exact construction costs as for-profit developers,” said Thom Armstrong, CEO of The Cooperative Housing Federation of BC and Rental Protection Fund board member.

“They also must deal with the same regulatory barriers that limit the quantity and quality of projects undertaken,” said Armstrong.

The panel made 16 recommendations, and number 12 is: “The federal and provincial governments independently or jointly create an acquisition fund to enable non-profit housing organizations to acquire currently affordable housing properties at risk of repricing or redeveloping into more expensive units.

“Conditions should be attached to this funding to prevent forced displacement of existing tenants when a building is acquired. The B.C. government should exempt non-profit organizations from the property transfer tax for building acquisitions that will be used to provide affordable housing.”

The fund is born

On Feb.8, the fund announced its first transaction.

The Community Land Trust of BC bought two co-operatives from The International Union of Operating Engineers Local 115. The pension fund had previously leased the land to the co-ops for 41 years. Last October, when the lease expired, the investor expressed its intention to sell the buildings.

The land is worth a hundred times more than it was 41 years ago, said Armstrong. It is located in Coquitlam, which will eventually be redeveloped at a much greater density.

“The revenue potential for a future owner and developer would suggest tearing the 290 rental homes down and building high rises,” said Armstrong.

“It’s great for the developer and the investor, but it’s a catastrophe for the tenants.”

The two co-ops, named the Tri-Branch Coop and the Garden Court Co-op, were sold at total market value to the pension fund, which has a fiduciary duty to protect its investments and distribute pensions yearly.

“That is why the fund is critical: it fills the equity gap between what the non-profit can pay for a property and what the market asks,” said Armstrong. “If we do not fill that gap, there is no possibility of keeping the rents affordable after the transaction.”

Thus, 290 families are guaranteed financial security, which will positively impact their wellness.

The fund has ripple effects on the rest of the market, said Maslechko. Housing is a continuum, and any intervention in one type of home influences others.

The Expert Panel report uses the analogy of a game of musical chairs. Players get priority access to chairs (homes) based on how much money or credit they have.

Player 1 goes first and may choose from among all the chairs, followed by Player 2, Player 3, and so on. In each round, the player with the least amount of money is left without a chair and must exit the game.

Boosting the housing supply is like adding another chair in each round rather than taking one away. While the first player will still have many more chairs to choose from than the last player, no one will be left without a chair.

Protecting existing affordable keeps chairs in the game for Player 2 so they do not take them from Player 3.

“Keeping Tri-Branch and Garden Court renters in their homes prevents them from going to the market and competing for the sustained very few affordable homes,” said Maslechko.

A portion of the renters in the buildings bought with help from the fund would compete for subsidized homes if displaced, but others would not because they are part of the “missing middle.”

Defined as workers like teachers, nurses and firefighters, the “missing middle” are an essential part of communities, said Atkey, and they’re losing ground in the current housing crisis.

“We are protecting the workforce housing,” said Atkey.

How the fund works

Most acquisitions will protect 30 to 40-year-old buildings owned by a private investor, a pension fund, a real estate investment trust, or a mom-and-pop landlord, said Armstrong.

The fund is managed by three member organizations: the Aboriginal Housing Management Association, the BC Non-profit Housing Association, and the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC, who sit on the board.

Most applicants seeking funding will likely be members of one of the three organizations.

To prevent any conflict of interest, an independent advisory committee examines all applications, said MJ Sinha, Chief Investment Officer of the BC Rental Protection Fund, who oversees compliance.

“The CEO of the fund has the final authority as for the contribution agreement with the applicant,” said Sinha.

Three criteria are considered when attributing the funding.

First, depending on the condition of the building, does the non-profit have sufficient financing to invest and guarantee a reasonable lifetime for the property?

The fund covers the equity gap between the price the non-profit should pay to keep rent affordable and the market price it needs to pay. For example, the Community Land Trust of BC received $71 million for its $125 million acquisition.

Thus, the non-profit must demonstrate it has access to traditional financing.

Second, does the non-profit have enough experience operating affordable housing to integrate the acquisition?

“Applicants need to be able to take on dozens of new residents relatively overnight,” said Maslechko. “It is different from the pace of a new development.”

That being said, smaller organizations can still achieve these criteria.

“We just want to make sure the acquisitions they’re bringing forward are contextual to their experience and existing capacity,” said the fund CEO.

Third, the amount required for an acquisition must allow the fund to meet its broader target.

“The BC government allocated the $500 million to preserve at least 2,000 rental homes,” said Armstrong. “That works out to an average of $250,000 per door in grant.”

So, an acquisition requiring $180,000 per door would be good, said Armstrong. However, if a proposal came at $300,000 per door, the fund committee would have to look at it more closely as it would exceed the average spend to meet the 2,000 homes the government targeted.

“It is a balancing act,” said Armstrong. “Non-profits need to carefully select their acquisition and negotiate the price tightly. So far, they have done a good job. We might be able to stretch the fund’s scope to 2,500 homes protected.”

“We are pleasantly surprised,” added Maleschko.

“Even in markets like Vancouver, non-profit housing providers are getting creative, diligently finding good purchases.”

Other solutions to protect affordable homes

The Rental Protection Fund offers secured capital contributions. There are obligations associated with the contribution. It is what distinguishes it from a grant, which doesn’t typically have ongoing obligations related to it, or from a loan, which is either repayable or forgivable.

In the U.S., the Impact Pool allocates low-cost loans. It protects the same tenants as the Rental Protection Fund: low-to-medium-income individuals and families, representing first responders, teachers, and service industry employees whose wages haven’t kept pace with escalating rents and housing costs.

The $115 million private fund is a partnership between the non-profit Washington Housing Initiative and real estate owner and operator JBG Smith.

In 2022, the Impact Pool provided $50 million to acquire 955 homes across three residential areas in Washington.

In Canada, the government of Nova Scotia launched the Community Housing Acquisition Program in 2022.

To acquire affordable housing units, community housing providers can access up to $10M in repayable low-interest loans. Nova Scotia government is considering adding an equity portion, inspired by B.C. Rental Protection Fund.

Financing is available for up to 95 per cent of the property cost for a term up to 30 years.

The first investment from the Community Housing Acquisition Program was a low-interest mortgage of $5.6 million to the Housing Trust of Nova Scotia to purchase five rental properties. Now, 295 affordable homes are protected.

In Quebec, the Community Housing Transformation Centre launched “The Plancher Fund” in May 2022.

It plans to pool co-operatives and non-profits’ real estate to create a leverage effect. The pooled equity would help non-merchant real estate providers buy or develop affordable housing or renovate their aging properties.

Quebec does not have a government fund like the B.C. Rental Protection Fund. Plancher is an ecosystem initiative, said Stephan Richard, development manager for the Community Housing Transformation Centre.

“It is our members’ equity that will allow us to borrow to acquire, build and maintain affordable housing,” he said.

After 18 months, Plancher is ready for a pilot project.

“We are discussing with the Quebec Housing Minister, France-Elaine Duranceau, and the Quebec Housing Society. For Plancher to offer below-market loans, we must combine market-rate private investment and no-interest government and Foundations loans,” said Richard.

“And we need the government to protect all real estate assets our members will commit to the fund.”

Plancher’s main challenge is the risk of losing the polled assets if deals go sour. That is why government asset protection is critical to the fund’s success.

The next step for the B.C. pilot project

The B.C. Rental Protection Fund is a pilot project, and members hope it could become a national initiative or be replicated in other provinces.

“We formally proposed to the federal Minister of Finance to set up a Canadian Housing Acquisition Fund that could be rolled out everywhere in the country. It would be administered by the Community Housing sector, not by CMHC,” said Armstrong.

The fund reports to the province every six months, with the following report due in April.

One of the critical metrics is the direct dollar impact in exchange for the fund investment. How many homes are protected, and what level of affordability is guaranteed?

”For every property we finance, we will compare the rents to CMHC’s latest median rental rates and B.C. housing programs as well,” said Maslechko. “And we will consider each regional context.”

At the time of the interview, 30 applicants had been pre-qualified; when they are ready for an acquisition, the process will be expedited.

“It is a race against the clock,” said Azaroff. “The fund’s process needs to be super quick, so we get our proposal to the broker as fast as our private competitors.”

Non-profit housing providers have been reactive. The fund already has a pipeline of 2,000 units. What comes next?

“What if the fund is depleted by the end of the year? Will there be additional non-repayable money?” said Azaroff.

“If Brightside had to repay the 65 per cent loan for Casa Mia, even at very favourable terms, we could not afford the Casa Mia acquisition without raising the rents.”