Can schools end child exploitation in Ivory Coast’s cacao fields?

Why It Matters

Your chocolate bar comes at a cost. The world’s chocolate industry is worth billions, yet the farmers producing its raw material remain impoverished. Despite efforts, child exploitation persists in Ivory Coast’s cacao sector. Is education a real solution—or just another promise that falls short?

Okabo lies deep in the heart of Ivory Coast’s cacao-producing hinterland.

A small village of 300, it recently became accessible by road—a dirt track—thanks to a World Bank-funded water purification project that pumps water from the nearby reservoir to provide clean water to the city of Issia, 144 km away.

As the water is meant for city dwellers, the villagers thirst for clean drinking water as they watch the reservoir water transported through their land.

The dirt road is the project’s sole unintended benefit to Okabo. Yet, the villagers are far from passive bystanders.

Okabo never had a school. Children had to walk seven discouraging kilometres on dirt to the nearest village, Coulibalikro, to attend classes.

Okabo’s residents pushed for their own school. In 2020, collaborating with the Ivorian government and farmers cooperatives, Save the Children Ivory Coast identified Okabo as a site needing intervention.

The NGO had initially planned a nine-month bridging class for Okabo’s children, who did not have formal education, to fastrack them for schooling. The classes were held on a one-hectare parcel of land donated by the village chief. However, this didn’t address a core concern: the distance from Okabo to Coulibalikro.

Determined, Save the Children and its partners helped the parents build a permanent school building. The organizations provided cement while the village arranged the rest of the construction materials. Two years later, the bridging classes became a community school. Parents found volunteers to teach.

The villagers continued their activism. With support and advocacy from Save the Children and local officials, the Ivory Coast government officially recognized the community school, turning it into a public school and ensuring its continuation with a paid director and trainee teachers in 2022.

Today, Okabo’s children can have a basic education without leaving their village.

The village’s story is part of the battle against child labour, including the worst forms of child labour (WFCL), a practice deeply embedded in the Ivorian cacao industry.

By constructing the school, Okabo residents ensured their children’s education and created conditions for taking them off dangerous work in cacao farms.

A nation built on cacao—yet impoverished

Ivory Coast is the world’s largest cacao producer, contributing to around 45 per cent of the global production. Eight million Ivorians depend on the sector. Family farms are the industry’s backbone, and around 1.2 million households are engaged directly in cacao farming. Twenty per cent of the country’s GDP and 40 per cent of its export revenue come from cacao production.

Despite the global chocolate industry soon expected to be worth US$200 billion—more than twice the size of Ivory Coast’s GDP—71 per cent of the Ivorian cacao-producing households earn less than CFA$1,500 (West African Francs) a day, about $3.40. More than 40 per cent live below the poverty line, earning CFA $500 or $1.13 daily.

Three million children live in Ivorian cacao farming communities. Close to a million children are believed to be engaged in cacao production, with an overwhelming majority performing hazardous work.

Slave labour, especially of migrant minors, is also present.

With neighbouring Ghana, the second biggest cacao producer in the world, more than 1.5 million children work in cacao plantations across the two countries. Nearly half of them are engaged in WFCL, defined by the International Labour Organization as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.”

Save the Children’s intervention in Okabo is part of Work: No Child’s Business, a five-year program from 2019 to 2024 financed by the Dutch government to combat child labour.

At the same time, Save the Children helped implement a United States Department of Labour-funded (USDOL) program to combat WFCL in the Ivory Coast’s cacao sector. Worth four million USD, the five-year program began in 2020. The program funding has been frozen since the Donald Trump administration decided to cull American foreign aid.

The Dutch intervention is based on the paradigm that schooling is the solution to child labour. The USDOL program includes initiatives to increase household income, community savings, and farming productivity to support families sending children to school.

The American intervention involves 50 cacao cooperatives in the Haut-Sassandra Region’s Daloa and Vavoua departments, representing thousands of small-scale farmers.

Child labour: beyond the headlines

Kandogona Soumaïla, an expert on cacao supply chain and technical advisor on child labour to international regulatory consortiums and NGOs, explained the background of the government’s efforts to eradicate child exploitation in Ivory Coast.

“Child labour started being covered by journalists who were investigating the cacao sector” in the early aughts, he said. “They focused on the worst forms of child labour, which they equated to forced labour or modern slavery,” Soumaïla explained.

The most famous journalist exposé, aired in 2000 by the UK’s Channel 4, showed young migrant men working in slavery-like conditions on Ivorian cacao plantations. A year later, further high-profile reports were published.

The response in Europe, the largest buyer of Ivorian cacao, was shock, and there was a real threat of boycott.

Save the Children channels the threat of consumer boycotts, a veritable Damocles Sword, in its awareness campaigns.

“The message we give to the producers is that if Western consumers stop eating chocolate, who will buy cacao?” said Bertrand Gueu, advocacy coordinator at Save the Children Ivory Coast, speaking in French.

“What will become of the producers? They’ll be poor. If they’re poor, they won’t be able to look after their children,” he explained.

However, Soumaïla cautioned that a better understanding of what constitutes child labour in the local context is needed, pointing to the tension between Western sensibilities and on-the-ground realities.

“When I was a child, I used to help on the farm with small tasks,” he said. “In rural communities, involving children in household and farm activities has long been seen as part of their education,” he explained.

The International Cacao Initiative, which fights against child labour in the sector, recognizes that socializing work does not endanger a child’s health, school attendance, or playtime.

But Soumaïla said that “today, some of these same activities are classified as child labour.” He added, “if a child is involved in a task that carries some level of risk, even if accidents rarely happen, it can still be labelled” as hazardous work.

Child labour: beyond culture

However, what lies beneath culture is also an unavoidable material reality: extreme poverty.

“One of the causes of child labour is the poverty of the cacao producer,” said Gueu.

“If the producer doesn’t have enough money, he can’t send his children to school,” he added.

The Socodabaz cooperative has thousands of cacao farmers as members. Its director, Yéo Doh, a former banker, left his successful corporate career to help cacao farmers improve their livelihoods.

Sitting in his office in Bazra town, just outside Vavoua city, he illustrated Gueu’s point with a typical example: “If I’m a father with no means, I can’t afford any help [for farmwork]. The only one besides me is my very young child. I have no choice but to rely on them.”

“For the planter, the land is the future,” Gueu said.

To ensure a financial future for the family, he said that parents consider children’s initiation into farmwork as crucial. He explained that in the face of necessity, whether children’s work is dangerous is not a concern for the families.

“To be initiated into cacao farming, you have to go out into the field. You have to work like your father. Tomorrow, if he’s no longer there, the son will be the heir,” Gueu said.

Beyond black and white: child labour and the law

The international exposure made it “possible to establish a regulatory framework and institutions to address all related issues,” Soumaïla said. “To define child labour, Ivory Coast refers to international conventions to guide its policies,” he said.

However, given cultural factors and the cacao sector’s importance to the country’s economy, the Ivory Coast government accepts that combatting child labour in all its forms isn’t a realistic goal.

“Even certification programs don’t require the complete elimination of child labour because they recognize that it’s nearly impossible,” Soumaïla added.

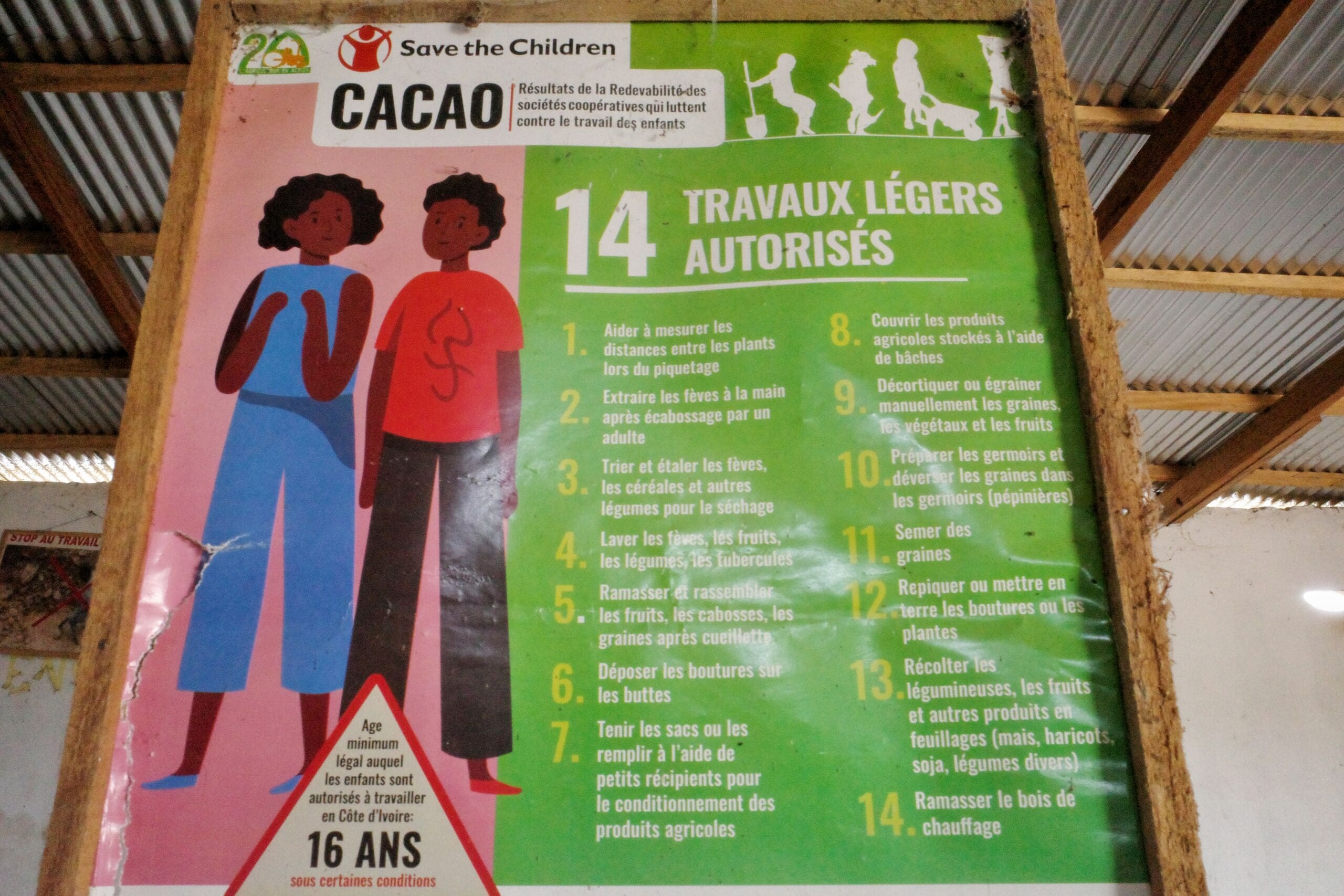

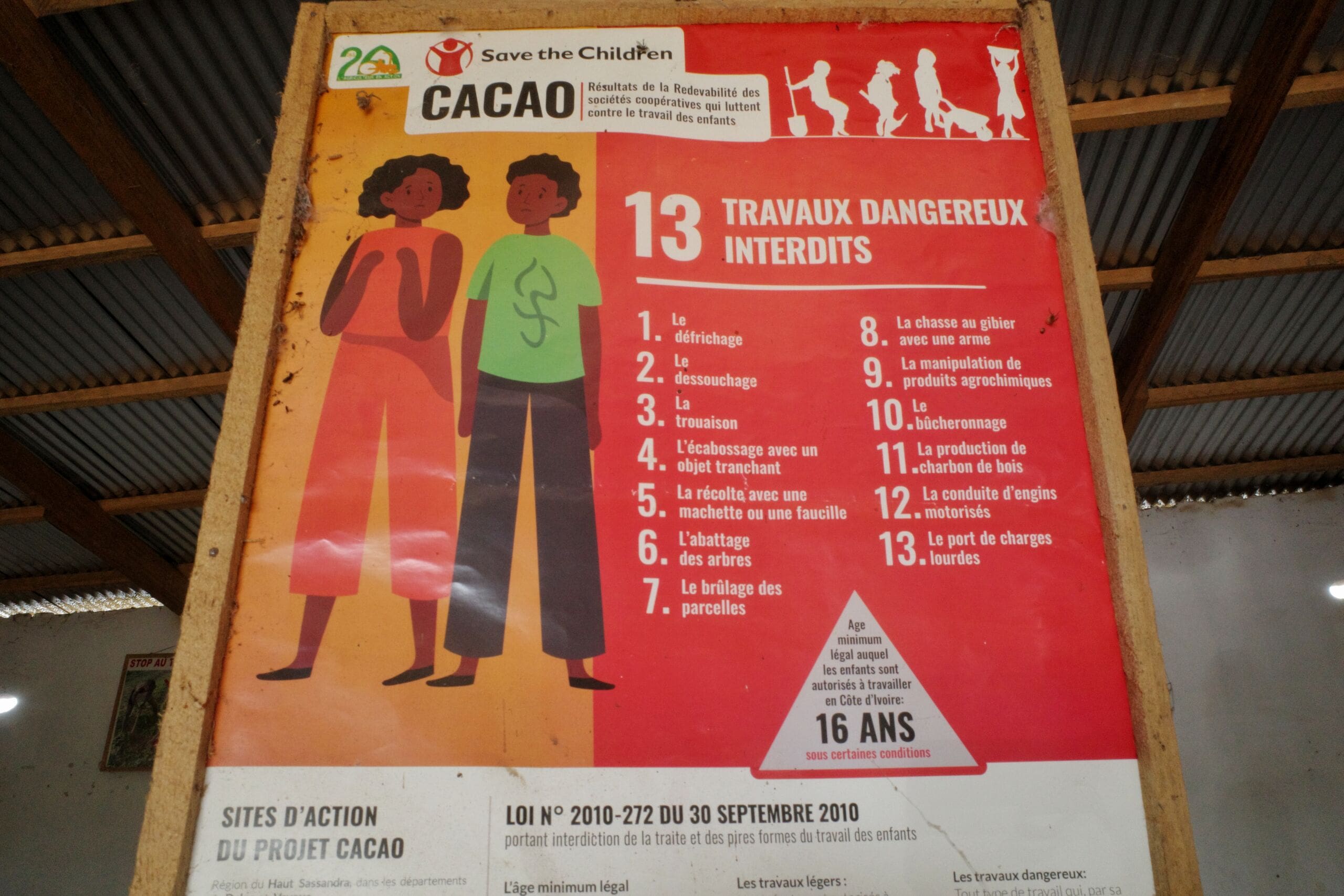

Instead, corporations and the state are focused on eliminating WFCL. To this end, the country’s parliament has passed laws distinguishing between permissible and illegal forms of child labour.

According to a 2017 law, children between 13 and 16 can perform specific tasks that don’t threaten their health. Farmwork is to be done outside of school hours. These tasks include light cleaning and lifting small weights, for example.

Hazardous tasks, including clearing farms and forests with machetes and burning farmland with chemicals, are banned for anyone under 18.

Building community trust

Gueu explained that given the centrality of child labour to cacao farmer wellbeing, even efforts to combat the worst forms of it can be a tough sell.

Soumaïla added that “parents and communities struggle to understand what they can ask their children to do and what is prohibited.”

He was critical of Save the Children’s campaign maxim, La place de l’enfant c’est à l’école, or “a child’s place is at school.” He characterized it as a top-down approach that fails to consider the cultural and social life of children who work on family farms and could be seen as imputing guilt to parents. However, he insisted on the importance of raising awareness.

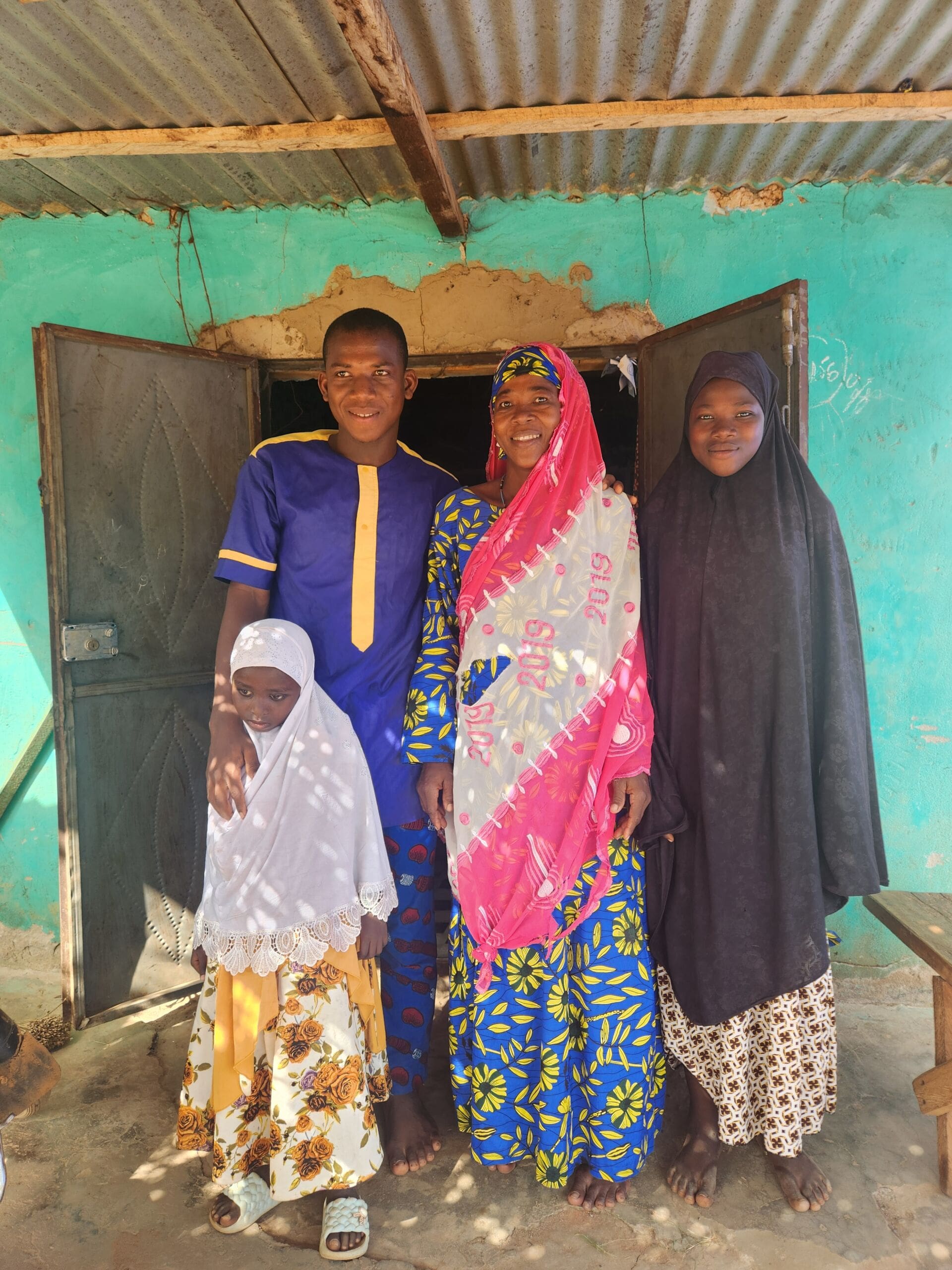

In the village of Buino, members of Le comité de protection des enfants, a group of social workers that campaigns for children’s rights in the locality, shared stories.

“The parents said in the beginning that we are complicit, that the whites brought us,” one member said. The “perception was that it was a collusion with Westerners to push through their practices,” another member said.

“They chased us away.”

Farmers “thought that if they, as fathers, can no longer have authority over their children, it will be because of us,” Gueu said. “If a farmer can’t maintain his plantation, issues of poverty will set in. And so he saw this as a threat.”

Antoine, a farmer and head of a family in Buino, explained why some families are unhappy with the intervention.

“If there are five on a plantation—me and my four children—and I’m told not to take them to the farm anymore, then it’s just me doing the work. It impacts me because I am [then] alone,” he said.

For their advocacy to be successful, Save the Children had to get village chiefs on board. “Village chiefs influence the population because they act as heads of state,” Gueu said. “They influence people to make cocoa farmers understand the fight against child labour. We have trained all the village chiefs where we operate,” he added.

The chief of Botifla village is a figurehead who allowed the organization to operate in the locality. The chief’s own life motivated his decision. Speaking with the help of a translator, he expressed his regret that he had worked as a cacao farmer all his life yet could not build any wealth. He attributed this to his father’s lack of resources to send him to school.

The chief somehow educated his children to avoid letting history repeat itself. The decision paid off: today, his children earn enough money to help their father live in a concrete house of his own—a sign of achievement in a village where such dwellings are hard to build.

The chief’s primary motivation to educate his children was income, not the fight against WFCL, though he knew the latter’s importance.

His and Antoine’s examples show that income generation remains the biggest concern in the Ivorian countryside.

Therefore, Gueu and Soumaïla said any successful intervention to combat WFCL must include efforts to improve cacao producers’ income.

Empowerment through community savings

Community-level savings and credit lending are one way to strengthen farmers’ financial capacity. Known as AVEC, Associations de valorisation de l’entraide communautaire, these mutual aid groups are open for villagers to join for a small fee. The members, averaging 30 per group, must contribute a mutually agreed amount weekly.

The group savings are then loaned to members to invest in revenue-generating activities and farmwork. They can also borrow money to pay for children’s education and healthcare.

The interest on loans, generally around 10 per cent, is invested back into the group savings. At the end of each year, profits are shared between members depending on their contribution ratio.

Given their precarity, banks refuse to provide loans to cacao farmers. If they do, the interest rates are double those of AVEC. Without formal credit, mutual aid is the mechanism for village-level lending.

AVEC promotion is part of Save the Children’s intervention. Its “role is to enable producers to have other sources of income,” Gueu said. “Cocoa is not produced all year round. It’s generally a cycle of two or three months.”

“There’s a long period when there’s no income. Hence, there is a need to set up AVEC so that, alongside the primary source of income, cocoa, there are other sources of revenue.”

Villagers spoke glowingly of the benefits. For example, the AVEC president in the village of Buino borrowed money to set up a small food business. She bought a freezer to keep the ingredients fresh and could travel to the capital, Abidjan, to sell her products. With the income, she bought supplies for her children to attend school.

Alfred, one of the AVEC facilitators in Buino, said this shows community lending programs can empower women since they no longer have to rely on husbands for financial support.

Women play a crucial role in the village economy. While men tend to the cacao plantations, women carry out small commerce in the markets to support their families.

A group of women in Botifla spoke of the need for women to have more earning opportunities to send children to school. Most of the women didn’t know how to read and write. They mentioned how they appreciate education when their literate children can help them with basic calculations and bookkeeping.

However, the women hinted that schooling is not the ultimate solution, noting rural children don’t necessarily find jobs after graduation.

Good intentions, bad outcomes

While the credit mechanism has empowered the members, not every activity is a net positive. The chief of Botifla explained that farmers can now borrow money to buy chemical products to clear farmland instead of relying on children for extra labour.

Previously, land clearing was done manually with machetes, and the intensive effort required more labour power, forcing farmers to put children to work. Chemicals’ effectiveness in clearing land also allows farmers to expand their farming area. With more production, their income also increases.

However, Gueu admitted to the environmental concerns of chemically burning extensive areas to increase farmland and pointed out that Save the Children does not endorse unsafe chemical products, known in the local jargon as total, since they burn everything thoroughly.

The use of chemical products risks exacerbating the unregulated expansion of cacao plantations, which is the primary cause of deforestation in the country.

According to research by the Stockholm Environment Institute, between 2003 and 2017, 1.65 million hectares of Ivorian tropical forests were cut for cacao production – equivalent to the same size of New York City annually. This constitutes 45 per cent of total forest loss in the country. Seventy-five per cent of cacao produced this way was exported to Europe.

Local experts called deforestation the price Ivory Coast had to pay to become the world’s largest cacao producer. Increasing output by expanding land availability is a trap many countries that rely on primary commodities export for income face.

Given the magnitude of the scale, development initiatives struggle to escape that logic at best and contribute to it at worst.

Greening the cacao industry

Aware of deforestation, Save the Children’s program includes an agroforestry intervention called champ école paysan, or farmers’ field school.

The program aims to increase cacao production while improving forest cover by planting taller trees to shade the shorter cacao trees, improving moisture in the soil.

Farmers, generally a group of 20 for each field school, are also taught pest, soil, and plant management techniques, cleaning, and ventilation to increase productivity.

“If we create field schools and the producer has all the techniques to improve his production, he has money,” said Gueu. “If he has money, he not only takes care of his plantation but can also send his child to school instead of putting them on the plantation.”

While walking through a cacao plantation in Botifla, a farmer shared his view of the field school.

He explained, with the help of a translator, that his farm was clean. He said he had received training that had enabled him to improve his yield.

The farmer said he and his father worked the field, and his children did not have to work the field. Now that his father has passed away, the farmer said the training he received helps him maintain the farm himself.

Dangerous chemicals: keeping kids safe

The use of chemicals for farm management is an inescapable fact. While Save the Children does not endorse harmful agents, it does not exclude pesticides and other agents altogether.

“In every community we work, we have trained a phytosanitary [pest and herbicide] applicator,” said Gueu. “Their role is to educate farmers on properly using phytosanitary products in cocoa plantations.”

“A well-maintained plantation yields higher yields, ultimately improving the grower’s income,” Gueu said.

“The applicators are knowledgeable about the products and understand that they are dangerous for children.

“They raise awareness and ensure that growers do not involve children in pesticide application,” he added.

When aid leaves: cooperatives as pillars

The Dutch intervention ended in 2024, while the USDOL program was supposed to end in June 2025 before the Trump administration prematurely stopped its funding.

While such projects are transitory, cooperatives like Socodabaz are permanent. The director, Doh, explained how his organization continues to fight for cacao farmers’ uplift.

“One of our roles is to ensure that farmers get the right price for their produce,” he said. The Ivory Coast government has fixed the per kilogram price at CFA$1,800, or $4.07. Buyers are supposed to buy cacao at that price.

The fixed price is low compared to the cacao prices in the international markets or comparable producers such as Cameroon.

However, farmers are forced to sell at even lower prices because they often cannot quickly get their produce to the market. They also sell at a discount to prevent cacao from rotting and wasting.

“Many communities are difficult to access because there are no roads,” Gueu said. “While some areas have main roads, many camps are far from these routes, making it impossible for trucks to reach them and collect cocoa,” he added.

To address the problem, Doh and his cooperative rent tricycles to transport cacao from remote plantations to a central location where trucks can pick it up. The cooperative’s profit from selling cacao finances these activities.

Socodabaz also invests in social programs to help farmers. Doh successfully advocated for a government hospital to be built on behalf of his community. The cooperative regularly surveys villages to determine how many families need financial support to send their children to school. Doh said he helps as many families as possible but admitted the demand is beyond his means.

The cooperative has also helped schools build dormitories for professors who are often unwilling to move to villages to teach if they don’t have proper accommodations.

Doh was adamant that building a school in every village was the way to combat child exploitation.

Okabo: a microcosm of Ivory Coast’s struggle

Back in Okabo, the village chief explained, with the help of a translator, that before the school was built, children used to go out into the fields with machetes to clean the cocoa.

But he said that once schooling became available, children no longer carried out dangerous tasks. On days without school, children still go to farms with their parents to do light work.

Okabo has a school but lacks electricity, clean water, a hospital, and a proper road.

The chief said that when children drink the water from the marigot, they get sick, and their parents must travel miles to take them to the hospital.

In this way, the village is a microcosm of Ivory Coast. It attempts to eliminate child exploitation, but not all child work is seen as inherently wrong. Therefore, while the villagers strive for their children’s schooling, the sociocultural practice of initiating children into family farmwork continues to exist in parallel.

In Okabo, schooling as an intervention successfully reduces children’s hazardous work. Still, deeper issues of cacao farmer poverty undermine the rights of children and their families in the village and across the country.