Code Red for Canada: First comprehensive study on the effects of climate change on human health has three key recommendations

Why It Matters

From record breaking heat temperatures gripping parts of the world in India and Pakistan and wildfires that ravage the West Coast to impacts on water and food security, climate change will continue to test the survivability of humanity.

This journalism is supported by the Future of Good editorial fellowship on climate change and human health, supported by Manulife. See our editorial ethics and standards here.

With spring came extreme flooding across northwestern Ontario, after seven weeks of record rainfall.

Residents in Kenora, Ontario had been issued evacuation orders. Highways were washed out and roadways flooded. With countless road closures, it became impossible for emergency vehicles and health responders to access those in need of help. For Pikangikum First Nation, about 500 kilometers from Thunder Bay, the flooding has impacted major infrastructure and their main source of drinking water. The only road in the community to access food and gas was flooded. Emergency operations with the Independent First Nations Alliance rushed in to deliver food, medical and construction supplies by boat and float plane.

This is just one recent example of many, where extreme climate events perpetuate health impacts, especially for those who are living in remote and under-resourced communities.

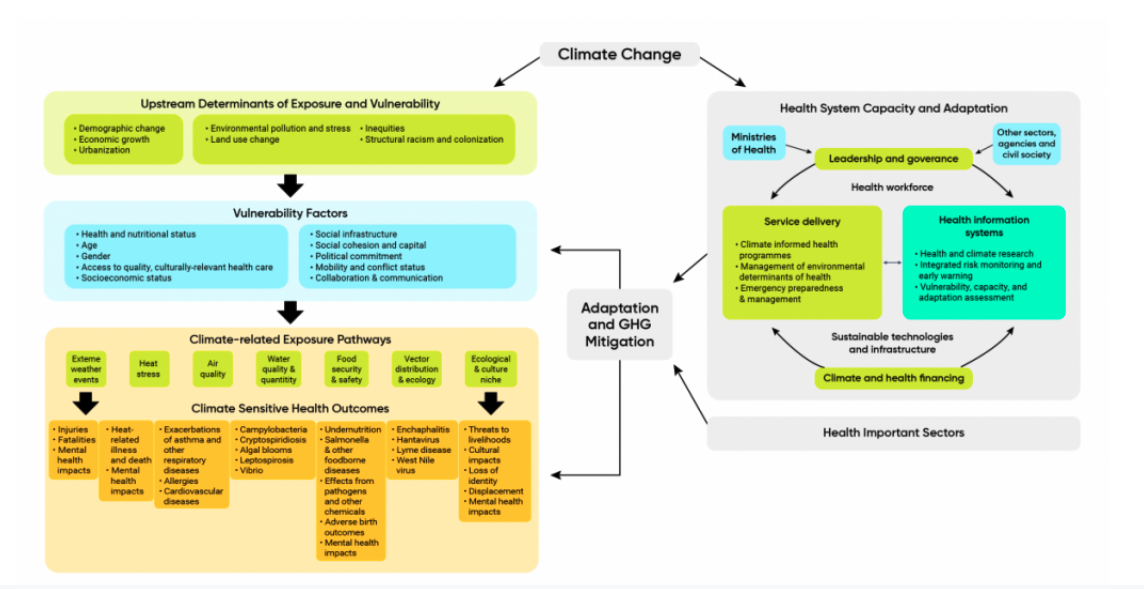

Canada, on average, is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, and the Northern region of the country is warming even faster. As the climate crisis continues to intensify, Canada is gripped by ongoing climate disasters and impacts — from flooding so severe it was dubbed an ‘atmospheric river’ to an unrelenting heat wave, called the ‘heat dome.’ Not to mention the pandemic, one of many viral threats amidst an increase of zoonotic disease transmission, caused by deforestation and environmental degradation. Climate change health related concerns include air pollution, infectious diseases, water and food-borne diseases, and climate-related natural hazards.

The wellbeing of not only the planet, but also of people who are part of the planet’s complex systems, is at stake.

In the first study of current and projected risks from climate change to the health of Canadians since 2008, experts across Canada have contributed to the report from the University of Waterloo, titled Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate.

A majority of Canadians who are aware of climate change worry about the impacts of climate change on their health, even if this report finds they don’t know exactly what those impacts might be. Additionally, health authorities and organizations have called for a climate resilient health system. With rapid warming, scientists warn of freshwater loss in Canada and increasing risk of water shortages in some regions during the summer.

The report demonstrates the knowledge gaps amongst Canadians on how climate change will impact (and is already impacting) their health, as well as solutions for governments and NGOs to implement for adaptation and mitigation.

The report findings help to not only inform the public but also equip the social impact sector with tangible tools and equitable solutions that will protect Canadians from health impacts caused by the climate crisis.

How climate change is already making us unhealthier

Spread of infectious diseases

The report provides a thorough analysis of a myriad of climate impacts on public health, from food insecurity and water quality to mental health. It also highlights lesser known impacts, the increase in infectious disease.

Researchers have found that with increased temperatures, along with environmental degradation and urbanization, comes an increase in disease transmission from animals to humans (zoonotic disease, such as COVID-19). Dr. Zahid Butt, assistant professor at the University of Waterloo School of Public Health Sciences and contributor to the report, explains to Future of Good, “When we disturb ecological systems, it increases transmission of disease from animals to humans, such as viruses like inipa virus that was spread from bats to pigs and then to humans.”

Warming temperatures are also responsible for infections transmitted by insect bites, also known as vector-borne diseases. In 2008 it was projected that climate change would increase the prevalence of Lyme disease, as ticks expand their range further into Canada from the United States, as a result of warming temperatures. There is now strong evidence that “Lyme disease emerged in Canada and spread northward as a result of climate change, causing a dramatic increase in human cases from 2009 to 2017,” according to the report. Other examples of evidence of increased insect Butt believes these risks “are most concerning and the more urbanization and deforestation we have, the higher likelihood of diseases. For example, in times of drought we see intensified transmission of disease with water scarcity and contamination.”

As Canadians have seen throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, long term access to care is critical when navigating new diseases, especially those that present chronic health complications. The social determinants of health of a person and their community can either exacerbate the complications of disease — or leave groups better supported for recovery.

For example, frontline workers in restaurants, grocery stores and hospitals were exposed to COVID-19 before the availability of vaccines. Meanwhile, those who benefited from remote work, individual households, and access to personal transportation were better able to avoid the virus. These factors are all social determinants of health and similarly will play into how people across Canada experience the spread of infectious disease.

Climate change is a “threat multiplier” for public health

Climate change is considered a “threat multiplier,” the report says, because its impacts are shaped by those social determinants of health. Inadequate housing, poverty and other systemic structural issues are all factors in determining how people’s health and well being will be impacted by climate change. For example, climate change can intensify poverty by affecting livelihoods and food security.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health as the non-medical factors that influence medical outcomes. These include the conditions in which people are born, grow, work and live, as well as the systems that shape conditions of daily life, such as colonialism and political policies. WHO lists education, job insecurity, food insecurity, housing, social inclusion, access to affordable health services, income and early childhood development as social determinant factors from these conditions. WHO states, “the lower the socioeconomic position, the worse the health.” Further, research suggests social health determinants account for 30-55% of health outcomes, according to WHO.

Berry explains: “Actions taken by decision makers outside of the health sector can really impact determinants of health. Climate change is such a broad challenge that our efforts to adapt will transform society for the better.”

What you need to know about how to adapt and mitigate

Improve the resilience of health systems

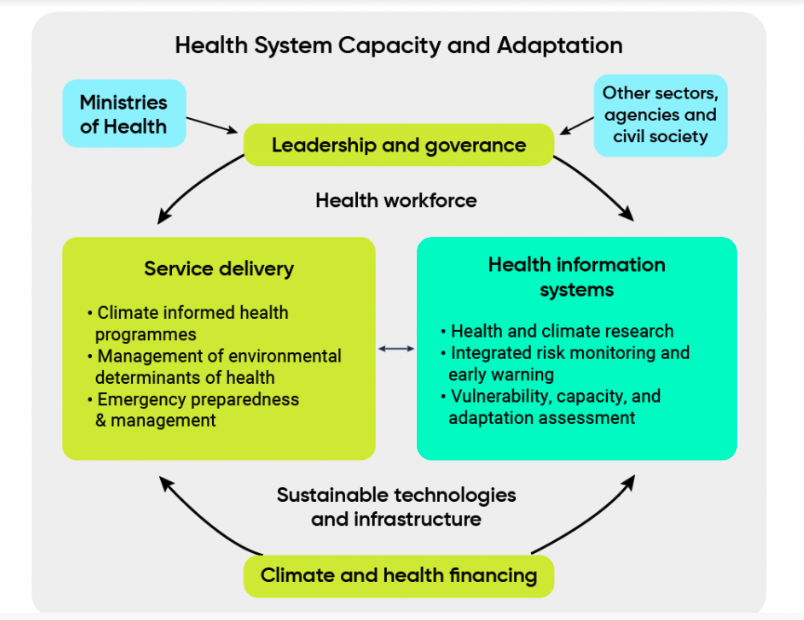

Given the serious threat of climate change impacts on public health, adapting health services is crucial. If health care systems fail, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, populations at greater risk of health impacts bear the brunt. The report identifies that health systems are already experiencing serious impacts and challenges from climate change. It is vital that health systems remain operational and sustainable over the long term to protect human health.

Peter Berry, lead author of the report (and senior policy analyst and science advisor at the Climate Change and Innovation Bureau at Health Canada), explains: “Climate change impacts on the health system and infrastructure is a big issue when these systems are necessary to protect people during crises. Even with hospital staff and paramedics, mental health challenges are intensified from climate events. For example, ice storms have affected health facilities, a flood in Atlantic Canada prevented health staff from getting to work, wildfires also impacted health facilities in BC where over 700 health professionals were displaced because of the fires and many were evacuated from health facilities.”

Calls for adaptation measures to improve health system resiliency are in tandem with philanthropic commitments to support climate change adaptation. Especially considering that hospitals are largely supported by philanthropic foundations, there can be room for greater support by resourcing community clinics and mutual aid initiatives.

The latest Canadian Philanthropy Commitment on Climate Change shows great potential for multi-faceted and robust partnership opportunities. The national commitment is “a call on all foundations and other funders in this land to signal their commitment to act on climate change regardless of their respective missions. If left unaddressed, the impacts of climate change can undo our work to advance equity, health, poverty alleviation, economic prosperity, Indigenous and human rights, especially those who will be disproportionately affected – and all issues and communities on which we hope to have a positive impact as philanthropic actors,” signatories of the commitment state. Multi-sector collaboration is necessary to support determinants of good health, such as housing, water systems, and food distributors, to prepare for climate change impacts on health. It is also possible with the resources, networks and leadership from the social impact sector.

Prioritize equitable adaptation and mitigation efforts

“How do we plan and respond to climate change impacts so we can improve health equity? Adaptation efforts really need to focus on those who are most at risk. For example, how can people with mobility challenges access a cooling center during a heat wave?” asks Berry.

According to the report, the populations at greatest risk of experiencing the health impacts of climate change include seniors, youth, those who are socially and economically marginalized, Indigenous Peoples, those with chronic disease and compromised immune systems, people with disabilities, residents of remote communities and frontline workers (such as firefighters).

The process for developing adaptation measures needs to be inclusive and invite participation from diverse groups of people who are experiencing systemic structural challenges like racism and colonialism, who can provide information about those challenges. Community workshops from local public health authorities can ensure voices from these groups are represented.

The social impact sector, such as social service organizations, can help build bridges between the government and communities they are already connected to. Organizations can help facilitate leadership and participation from communities with government adaptation and mitigation projects. By fostering ongoing community partnerships and supporting more meaningful involvement, leadership and co-direction on climate action, the social impact sector can address these equity challenges.

Different phases of adaptation can apply to civil society organizations and the social impact sector. Adaptation is outlined in the report in a series of steps. The first being to build awareness, this can include communication campaigns to inform the public about climate change and health, such as wildfire impacts on health. Followed by groundwork, which can look like monitoring risk to adequately prepare. Along with concrete adaptation, such as climate informed policies, upgraded climate-resilient health infrastructure, increased funding to climate change and health initiatives. Recently, the Canadian Medical Association and Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, have stated the gravity of climate change and offer climate change training for nurses and doctors to build their capacity.

Key tenants for adaptation risk management include regular climate change, health vulnerability and adaptation assessments; Indigenous partnerships, and stakeholder engagement. The report concludes that health adaptation is most effective when it is proactive and anticipatory, rather than reactive.

Participate in multi-sector solutions and collaboration

To address the main concerns throughout the report, Butt emphasizes cross-sector partnerships, from non-governmental organizations and governmental organizations to the grassroots level.

“We need to have collaborations in the social, health, education and environment sectors, the more collaborations, the better to address climate change. If we don’t have these partnerships and collaborations, we can’t enact better systems to address climate change and protect public health,” Butt says.

He recommends some possible solutions: “A joint task force for climate change and health with representatives from social, health, education and environment sectors could be formed, which could meet on a regular basis to discuss and plan for climate emergencies. At the community level, education and awareness about climate change and its impact on health could be initiated in schools and communities. These awareness campaigns or programs can be jointly provided by public health and health care workers and educators. In this way, collaborations can be established between the education and health sector, which could be beneficial in case of extreme climate events. Additionally, food banks and the housing sector could work together to address food insecurity and unstable housing; these services could then be extended in extreme climate events such as flooding and wildfires.”

The social impact sector, including non governmental organizations, can play a critical role in offering support to different demographics navigating the impacts of climate change and health. Berry explains, “There is a huge role to play. Especially for women, children, youth and older adults, people with chronic disease, the homeless, all who are often more at risk because of greater sensitivity to climate change. Women’s shelters and food banks, for example, are the adaptors.”