4 reasons why social housing is a good investment, and 7 smart tips to stretch those investments further

Why It Matters

Canadian governments have recently accelerated their investments in community housing in response to the affordable housing and homelessness crises. However, economic uncertainty and budget cuts could affect these efforts. Leveraging the maximum amount out of housing investments is essential.

In Quebec, the government recovers $1.38 million for every $1 million invested in social and community housing construction.

That’s the key finding of the report “Le logement social et communautaire: un investissement qui rapport au Québec,” funded by the Quebec Association of Technical Resources Groups and co-authored by economist Martin Saint-Denis and anthropologist Emilie Dazé.

The report notes that the savings include tax returns from the economic activities generated by these investments.

It also accounts for other savings realized by government departments and provincial and municipal agencies, pegging those at an estimated minimum of $354.9 million.

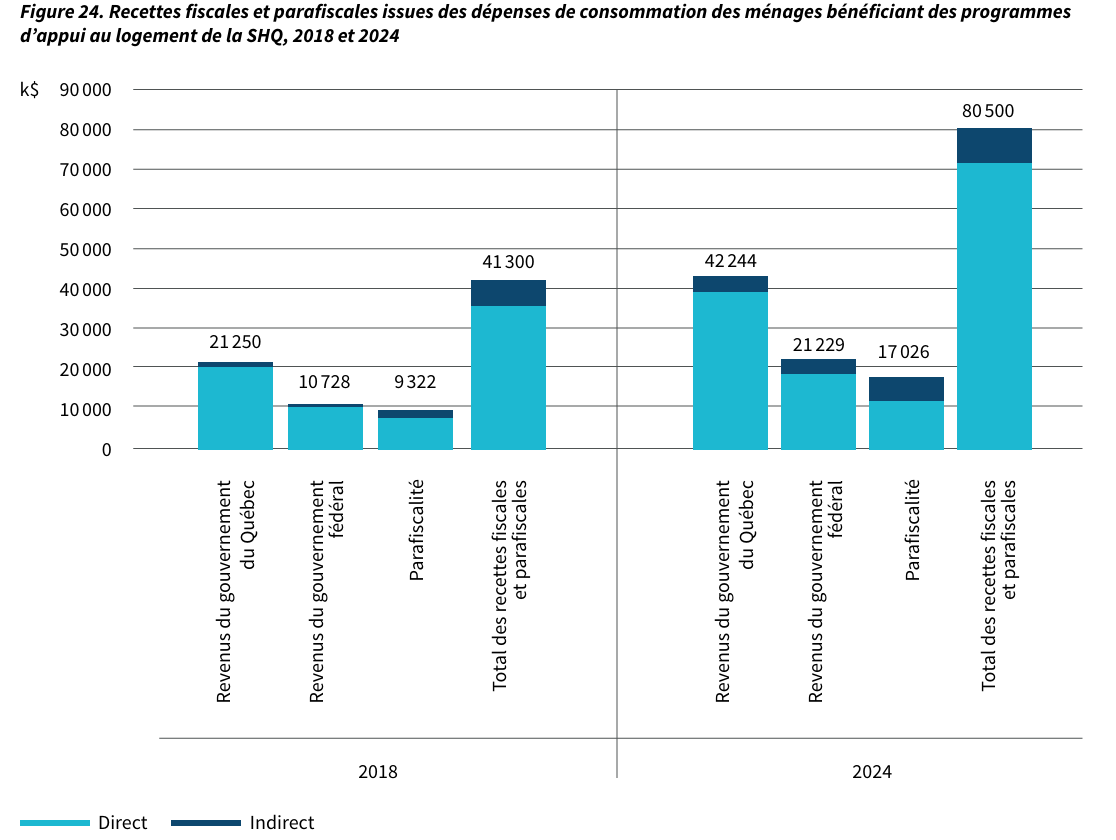

In addition, Saint-Denis quantified the “invisible” impact of social and community housing investments, such as maintaining the $367.4 million purchasing power for rent assistance program beneficiaries in 2024.

Saint-Denis projected where these tenants would inject some of these millions back into the Quebec economy, with about $42 million going back into provincial coffers, $21 million to the federal government, and $17 million for specific taxes like sales tax. This is about 21 per cent of the rent assistance program dollars.

Dazé conducted a deep dive with 25 housing resources and beneficiaries to highlight how to stretch these brick-and-mortar investments further.

First, let’s take a look at the four categories of cost savings.

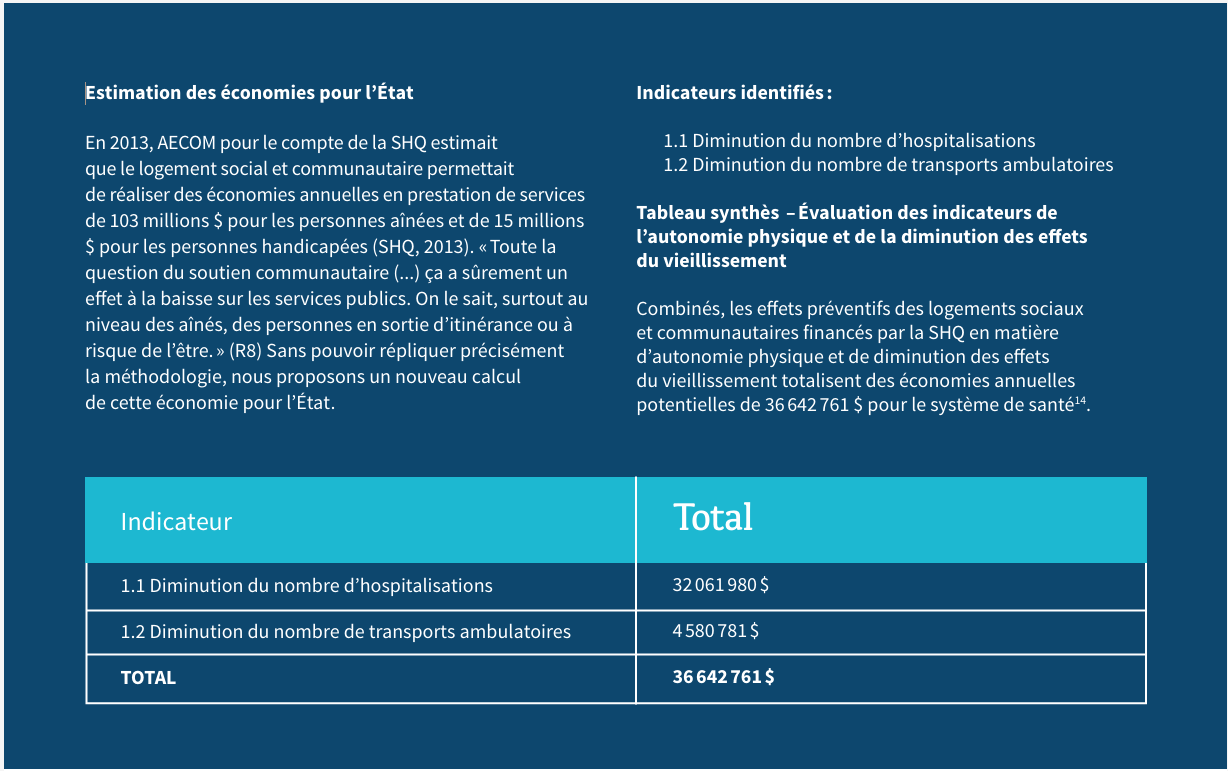

Cost savings 1: $36.6 million from keeping people with disabilities and the elderly safe in their homes

Maintaining the physical autonomy of vulnerable populations pays. Without this support, vulnerable people experience a greater dependence on public services and an increased risk of injury and isolation.

A reduction in ambulance use and hospitalizations saves Quebec $36.6 million.

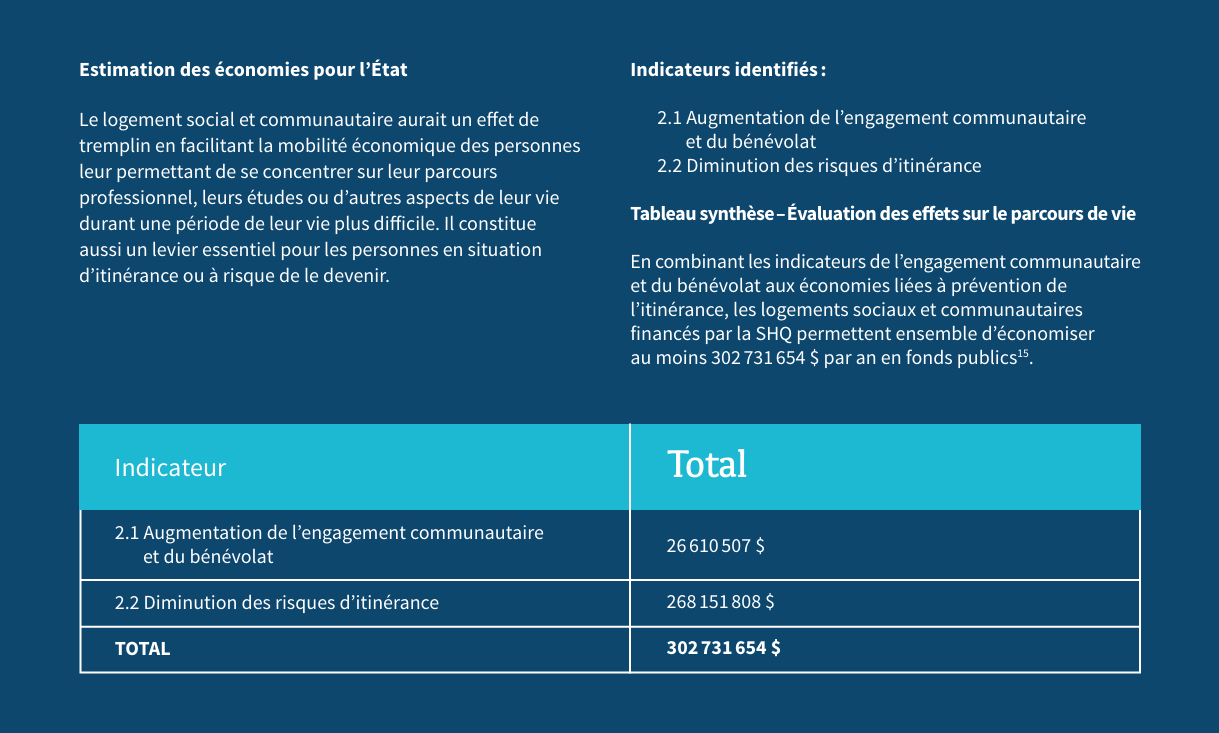

Cost savings 2: $302 million from socio-economic mobility

Social and community housing residents see their socioeconomic mobility increase over time.

According to the study, the most visible effect is improved mental health. Stable social housing frees up the psychological and physical space to study, return to work, or engage in social commitment.

The authors considered various types of social and community housing, including co-operatives. Co-operative living also enabled democratic governance and administrative skills.

According to the study, these skills facilitate access to opportunities, enabling residents to adapt to environments requiring a degree of autonomy and initiative.

The authors looked at increased community and social involvement and reduced risk of homelessness, which resulted in estimated annual savings of $302 million.

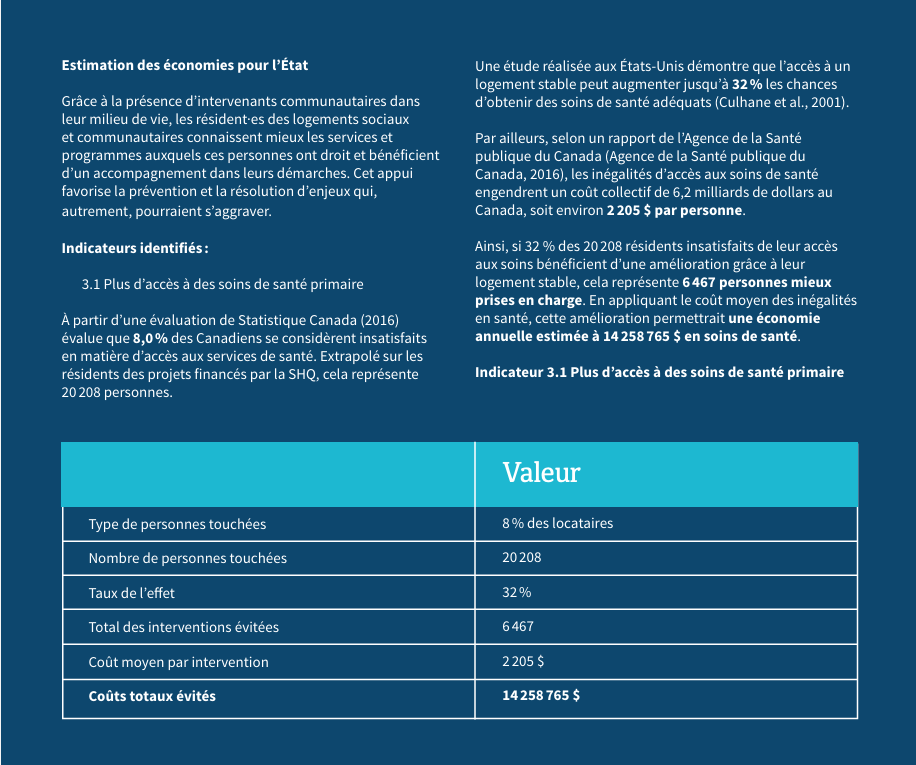

Cost savings 3: $14.2 million from better and more timely access to health services

According to Statistics Canada, about eight per cent of Canadians are unsatisfied with their access to health services.

Community workers help residents of social and community housing receive better access to government services and programs.

About 252,600 Quebecers live in social and community housing financed by the Société d’Habitation du Québec; eight per cent of them amount to 20,208.

A U.S. study states that access to stable housing increases the chances of accessing healthcare by 32 per cent, said the authors

Considering the eight per cent reach and the 32 per cent effect, the estimated annual savings from better access to health services for social and community housing residents amount to $14.2 million.

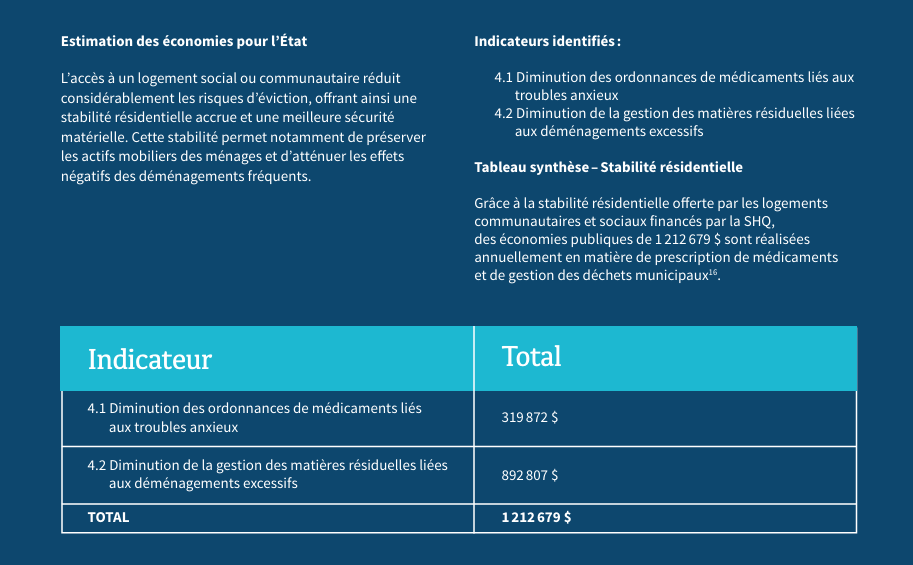

Cost savings 4: $1.2 million from the mental and financial damages of evictions

Stable housing is a source of “material security,” said the authors.

Social and community housing are considered stable housing. These units reduce eviction risk for tenants, lowering anxiety.

Losing a home often means losing your belongings, said Dazé.

“For people in precarious economic situations, these goods were often challenging to acquire. If they are ever replaced after an eviction, it will take a long time,” she said.

These belongings end up on the sidewalk on eviction day. Aside from the individual psychological and financial loss, there is a societal toll.

These abandoned fridges or mattresses must be collected, adding to the cities’ waste management budget.

Fewer prescriptions for anxiety disorders and lower waste management costs from stable housing add to annual savings of $1.2 million.

7 smart tips to increase the impact of social and community housing

How can governments, individuals and communities get more from the dollars invested in social and community housing?

Dazé’s deep dive into community housing organizations provides smart tips on leveraging these investments across all provinces.

The answer is timely, as the provincial and federal governments are accelerating their investments in response to the convergence of the housing and homelessness crises across Canada.

Between 2014 and 2024, the total annual financing of Québec community housing organizations rose from $1.5 million to $9 million.

SHQ also increased the sums devoted to unit construction from a low of $1.5 million to more than $400 million.

Smart tip 1: A little design goes a long way

Balconies could be considered a luxury. After all, what counts is having a roof over your head, right?

Think again, said Dazé. “Many newly housed homeless people sleep on their balconies for weeks before getting over the sense of confinement of their four walls,” she said.

“We all need to feel safe in our own homes,” said Hannah Brais, head of research for Mission Old Brewery, a Montreal organization that has been addressing homelessness for 135 years.

“Our homes are a source of wellbeing. It is even truer for those who have lived on the streets,” added Brais.

Smart tip 2: Sometimes, loneliness is worse than homelessness

Shelters have cafeterias, communal spaces, and employees. Meetings with social workers punctuate residents’ lives, and some activities are organized.

Brais said post-shelter apartment life can be lonely for those who do not work and for older citizens.

“Loneliness and boredom are real. Some residents need animated activities in their buildings and planned outings,” said the researcher.

Without these, some choose to go back to the animation and the support of shelters.

Some residents with mental health issues also return to shelter life because they are afraid they will harm themselves or others.

“Apartment life without sufficient support from social or medical workers is a source of stress,” added Brais.

Smart tip 3: Home maintenance is not a given

Maintenance is as essential as design, said Dazé.

“We hear horror stories about the decrepit state of the public housing stock. Some units are empty because they’re too dilapidated. Others are still in use, but they should not be because they are no longer habitable,” she said.

Residents need to learn how to maintain their homes.

“When you’ve lived on the street, maintaining a kitchen, taking out the trash and managing the pipes in winter, that’s not part of your essential skill set,” she said.

Once again, the role of a social worker or other contact person is critical for a lasting effect from the social or community housing.

Smart tip 4: Migrants are not a category; they are plural

We must consider intersectionality, said Mauricio Trujillo Pena, coordinator for ROHMI, a group of housing accommodation organizations for migrants.

Migrants are not a persona, he said. There are single men, families, single mothers, people with disabilities, queer folks, people with post-traumatic stress syndrome and others.

“We need to validate each newcomer’s mental and physical state to direct him or her towards housing fitting his or her situation,” said Trujillo Pena.

ROHMI member organizations own about 250 beds, some for women or single mothers, to provide this clientele with security.

In addition to the person’s situation, there’s also their background to consider: asylum seekers, refugees, temporary workers or international students.

“If we consider the specific situation of each migrant, we facilitate the integration process. But our members’ housing stock is insufficient; we must be creative,” said Trujillo Pena.

One of ROHMI’s members has teamed up with Concordia University, which has made apartments available. The group also works with private landlords, renting them a block of flats for its migrant clientele.

“This reassures the landlords for the first year; when they see that things are going well, the second lease is signed directly with the newcomers,” says Trujillo Pena.

Smart tip 5: A subsided home + intervention + support = autononomy and integration

The community organization Mères Avec Pouvoir (Mothers With Power) has existed for more than 20 years.

“We’ve been around long enough to observe the results of our interventions on many cohorts,” said Emilie Rousseau, coordinator for Mères Avec Pouvoir.

Their clients spend three to five years in housing provided by the community organization. They are single mothers with children aged between zero and five.

To live there, all must have a goal: returning to school, career re-orientation or any other professional project.

Mères Avec Pouvoir accommodates 30 women and their children in housing owned by Montreal-based NPO Interloge, which has 1,000 units across the city.

“Every woman in our program signs a lease directly with Interloge; it’s part of her empowerment process,” said Rousseau.

The residents have access to a sexuality counsellor, an educator specializing in child development and coaches for their professional projects.

“And we have an agreement with a Centre de la Petite Enfance (Québec public daycare network) located next door to the apartments. Each resident has a place in a daycare centre for their children. That, too, is part of the recipe for empowerment,” said Rousseau.

At first, Mère avec Pouvoir residents experience a “honeymoon period” where they are hopeful and motivated.

Three or four months later, they tend to break, said Rousseau

“They leave the survival mode, making room for all they’ve repressed. We say they settle down to decompose and rebuild,” said Rousseau.

“My teammates rock! ” noted Rousseau, adding they accompany women to the gynecologist, the lawyer, the accountant, and the pediatrician. At the end of their stay, 85 per cent of their clients leave with a diploma.

Rousseau sums up Mères Avec Pouvoir’s 20 years of proof of concept.

“Social housing becomes a springboard when it looks beyond emergencies. A few months or a year is too short to help a person’s life. We must take the time to provide residents with the proper support and guidance,” she said.

Smart tip 6: Mixed-use should not be a dogma

“One of our members partnered with an organization that provides emergency and transitional housing for people experiencing homelessness,” said Trujilloe Pena.

It didn’t work out. The cohabitation of asylum seekers and people suffering from substance abuse and psychological problems proved problematic for two reasons. One, tenants’ situations were too different, and two, the skills of the interveners were not interchangeable.

Dazé cites the cases of neurodivergent tenants as another example.

“They need a living space whose parameters they can control: noises, smells, and the layout of objects. Their home is their bubble, where they can settle down,” explained the researcher.

Therefore, mixed-use cannot be a dogma for social and community housing.

“Some audiences are more compatible than others. It’s by observing and listening that we find the best combinations. Those that make all tenants feel at home. That’s what makes all other projects possible.”

Smart tip 7: Revenue should also not be a dogma

What happens when a social or community housing tenant sees her financial situation improve? Should she leave to make room for a more vulnerable tenant?

“We do not ask the tenant of a private unit to leave because she pays the rent on time,” said Brais. Social housing is home just like private housing, she added.

Dazé sees several rebound effects in requiring tenants whose income exceeds the qualification threshold to leave.

It can be detrimental to the development and enrichment of some tenants. They may fear that they won’t be able to find another home.

It can also return tenants to a precarious situation.

“The enrichment can be temporary,” says Dazé. In these cases, the tenant is evicted from the more expensive private housing they have rented and finds themself in a precarious situation.

“This creates personal suffering and additional pressure on housing services,” said the researcher.

If the tenant wants to stay, Dazé and Brais suggest adjusting the rent to reflect their improved financial situation.

The AGRTQ report concludes that public social and community housing investments are “economically efficient and socially essential.”

And that they could do even more.