Who stewards 10 of Canada’s biggest community foundations’ investments? Mostly white men in finance

Why It Matters

Canadian foundations invest far more money each year than they grant out to charities. This means that their volunteer ‘investment committees’ — the group that oversees the foundation’s investment decisions — play a considerable role in the overall impact the foundation has. Some social impact leaders say that the “monocultural” nature of these committees is limiting their capacity to create systemic impact.

This story is part of the Future of Good editorial fellowship covering the social impact world’s rapidly changing funding models, supported by Community Foundations of Canada and United Way Centraide Canada.

If you’ve ever sat on a board, you know that committees are where the action happens. It’s for this reason, non-profit leaders say, that having a diversity of committee members’ viewpoints matters.

Within the last two years, several new reports have highlighted the diversity gap facing the non-profit sector. Yet, to date, no research has assessed the diversity of foundation investment committees — the body with the greatest month-to-month oversight over foundations’ largest asset pool: their endowment.

With that context in mind, Future of Good analyzed the racial, gender and professional diversity of members of the investment committees of the top 15 largest Canadian community foundations — a group that collectively held more than $5.8 billion in 2019, the latest year with comprehensive data. (See the end of this story for more information about our analysis methods.)

Five of these foundations — the Vancouver Foundation, Winnipeg Foundation, Toronto Foundation, Victoria Foundation and the Ottawa Community Foundation — were unwilling to verify the gender and racial diversity of their committees.

But amongst the 10 foundations who did, our analysis found that white men with finance experience are vastly over-represented. Eighty-nine percent of committee members are white, just 37 percent are women and 82 percent have backgrounds in finance. Further, half of all the foundations analyzed have all-white investment committees; and just one committee had more women than men.

The results “aren’t shocking,” said Liban Abokor, a working group member with the Foundation for Black Communities, but they raise important questions about “whether our investment strategies have really been aligned to our missions.”

What’s an investment committee?

The role of foundation investment committees is important.

In Canada, the majority of foundations orient toward ‘perpetuity’ — a feature which often demands that foundations earn more each year in interest on their invested endowment than they send out the door in grants. In the past several decades, community foundations have grown considerably across Canada, increasing the responsibilities of their investment committees. From 2013 to 2018, for instance, the assets of the top 15 largest community foundations nearly doubled in size.

To steward donor dollars, foundations turn to two groups: private sector asset managers (who are paid by the foundation to invest and manage their funds) and volunteer investment committee members (who oversee the asset managers). The latter group has several key roles.

First, they’re the team that drafts and revises their foundation’s investment policy, the document that outlines the investment approach taken by the foundation. This policy guides important ‘mission screens’ — for instance, whether it’s acceptable for a foundation to be invested in fossil fuel companies or real estate investment trusts (REITs) — businesses that can work at direct cross-purposes with the charitable aims of the foundation.

Second, the investment committee oversees the hiring of the foundation’s investment managers — one or several firms that make and monitor investments on behalf of the foundation. In this role, the committee can assess the asset manager’s financial track record, staff diversity, and commitment to social impact.

And finally, the investment committee can exert pressure on the investment managers. While investment managers have full discretion to make day-to-day investment decisions on behalf of the foundation (within the guidelines of the foundation’s investment policy), the investment committee can apply soft pressure, prompting managers to reconsider particular investments.

While ultimately the investment committee reports to the foundation’s board of directors, functionally, these committees have considerable autonomy and decision-making power.

“In my time here, I haven’t seen a board ask — or tell the investment committee: ‘We don’t think that’s a good decision, why don’t you go back to the drawing board?’” said Eugene Lee, vice president of investments with the Vancouver Foundation. Lee has been with the foundation for five years, he said, and during that time, the foundation’s board has always stuck with the investment committee’s recommendations.

Committees are a “monoculture,” says one leader

Though foundations aim to disproportionately serve community members with the greatest needs, the committees deciding on the fate of their foundation’s investments are disproportionately systemically advantaged.

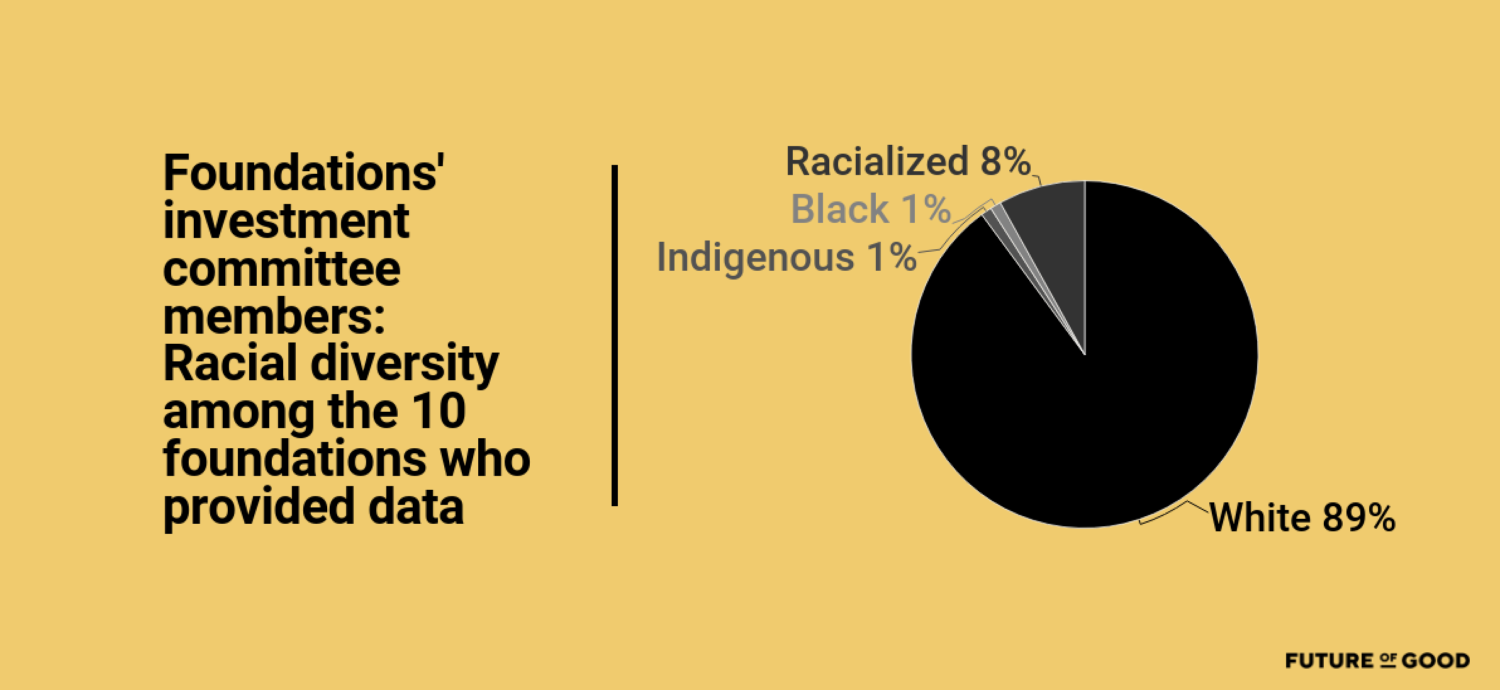

Amongst the 10 foundations who provided data for this analysis, eighty-nine percent of committee members are white. Further, across all committees, there is just one Indigenous member (1 percent of total), one Black member (1 percent of total) and six racialized members (8 percent of total). For context, the 2016 census identified that in Canada, 72 percent of people are white, 6 percent are Indigenous, 4 percent are Black, and 19 percent of people are racialized (numbers add up to 101 due to rounding).

In addition, half of the 10 foundations analyzed have all-white investment committees.

There are no Black people, Indigenous people or people of colour on the investment committees at the Hamilton Community Foundation, Saskatoon Community Foundation, Kitchener Waterloo Community Foundation, Niagara Community Foundation and the South Saskatchewan Community Foundation.

“What this reveals is the monocultural nature of Canadian philanthropy,” said Abokor. “And it begs the question…what are the kinds of investment portfolios that are created?”

In response, foundations emphasized their commitment to racial diversity. “Absolutely more needs, and must, be done to seek out equity and diversity,” said Carm Michalenko, CEO of Saskatoon Community Foundation, by email in response to the data. “After all, we are a ‘community foundation’.”

Michalenko said that the board met recently to discuss recruitment strategies to ensure diversity on the investment committee, “including a more open call for Board members and actively going to where diverse communities are found.”

Men are majority on investment committees

And what of the gender diversity of the largest community foundations in Canada?

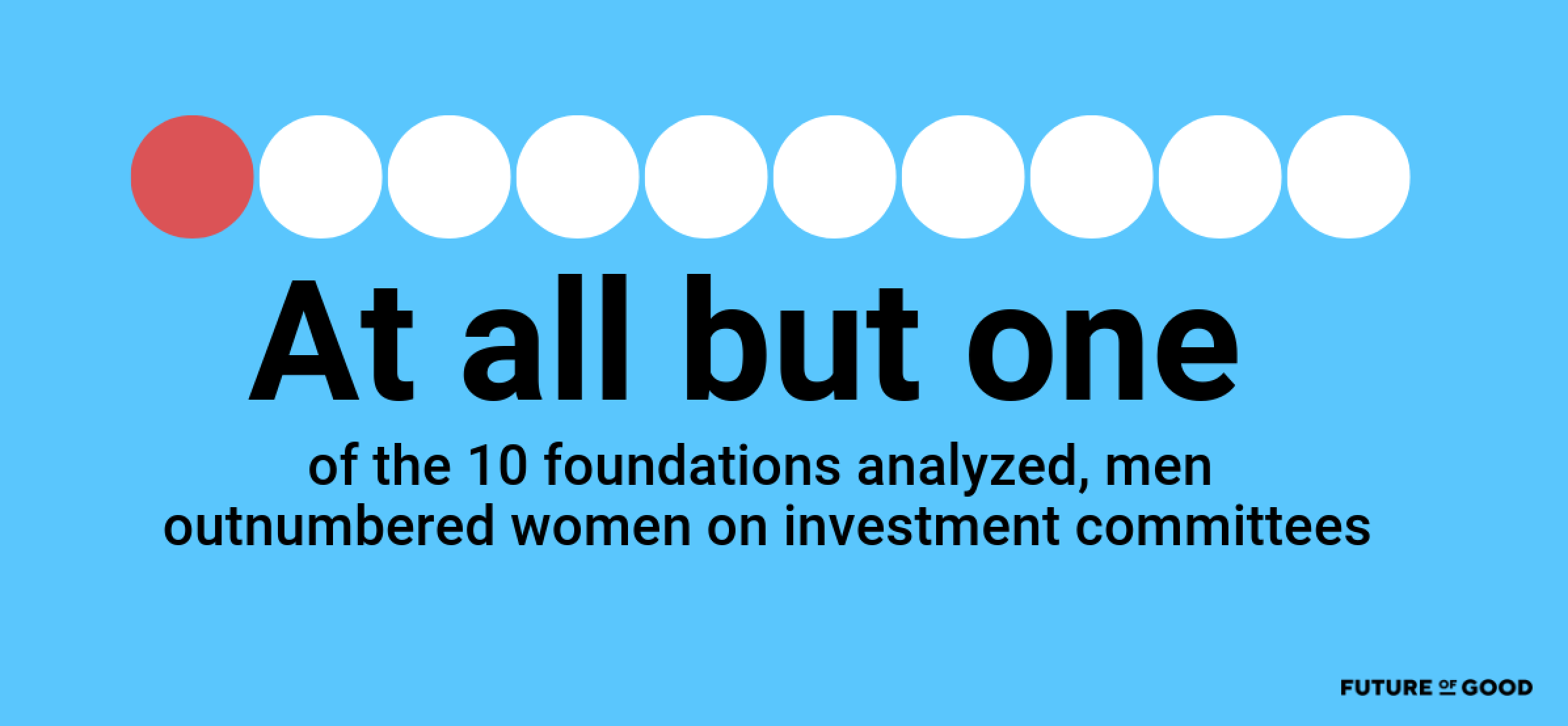

“It’s an old boys club,” said Jess Bolduc, executive director of 4Rs Youth Movement, former member of the board of directors of Community Foundations of Canada, and co-chair of Algoma Community Foundation. “There are folks who hold the power in those spaces and they reinforce the power in those spaces — and they aren’t willing to put in the research or the work to find others who are doing good work in the field.”

At all but one of the 10 foundations analyzed, men outnumbered women on investment committees. The Oakville Community Foundation and Edmonton Community Foundation had the highest percentage of men committee members, with 83 and 80 percent of men respectively. There are no self-identified gender queer or non-binary members across the committees analyzed.

One explanation offered for the low rate of women on investment committees is the gender diversity of the investment field at large.

Though the Winnipeg Foundation did not confirm the gender diversity of their committee, LuAnn Lovlin, the foundation’s director of communications, said by email that recruiting women onto their investment committee has been “more challenging” as a result of “so few women in the institutional investment field.”

In Canada, men slightly outnumber women in the finance sector, but this gap is most prominent amongst senior-level staff — a group commonly recruited by investment committees. In 2015, half of all chartered professional accounting graduates in Canada were women; but among executive officers of finance companies, a recent report found that just 21 percent were women.

Yet despite this hurdle, some foundation boards have been able to successfully recruit women to their finance committees. At the Hamilton Community Foundation — the lone foundation amongst the fifteen where women outnumbered men — 75 percent of committee members are women.

This has been achieved through increasing the diversity of their board and committee recruitment teams, enabling the foundation to reach more women, said the foundation’s CEO Terry Cooke; and as a result of a commitment to recruit people with diverse professional skill sets to the board — a feature not common amongst the group analyzed.

What if investment committees had teachers, librarians or activists?

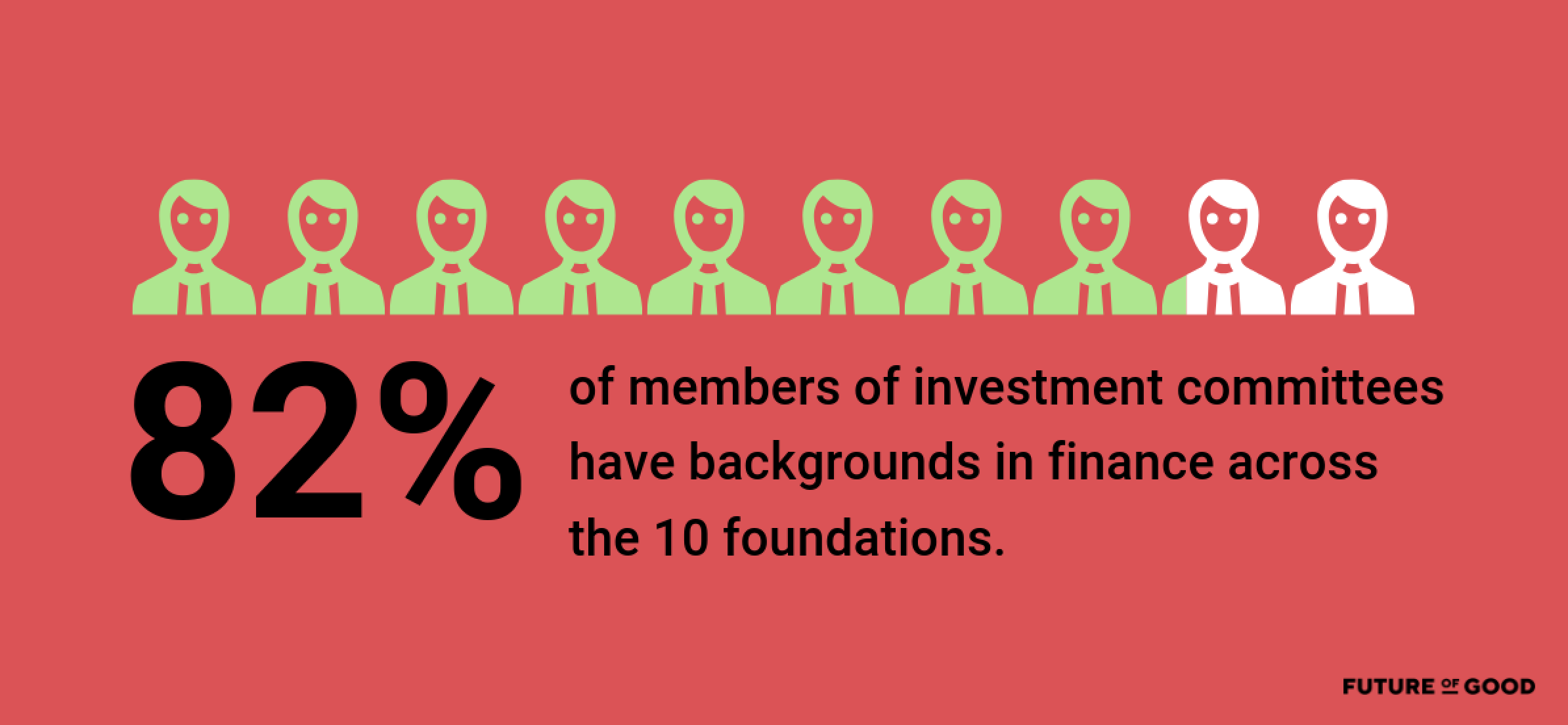

Across the 10 foundations, 82 percent of members of investment committees have backgrounds in finance. Members are portfolio managers, venture capitalists, pension fund managers, professors of finance, and other professionals with finance expertise. Further, across the group, nearly 20 percent of committee members currently or have worked for one of Canada’s major banks.

At the Vancouver Foundation, one of the foundations that would not confirm board diversity data for this analysis, this focus on financial expertise is intentional, said Lee, where committee members are sought based on their knowledge of specific financial ‘asset classes,’ such as private equity or public infrastructure. This allows for the committee members to offer targeted oversight to the 17 different asset managers employed by the foundation, including several who have a focus on environmental, social and governance-screened investing (ESG) or responsible investing, he said.

The same is true at the Winnipeg Foundation, where “extensive institutional investment experience is a priority in helping determine investment committee members,” said Lovlin.

But for Abokor, this near-exclusive focus on finance experience across the country poses concern.

“We want folks with investment experience helping guide us with a steady hand. But you also want individuals who are thinking about mission-related investments,” he said. For Abokor, it’s not essential that each committee member has deep financial expertise.

“What’s to say that there couldn’t be an academic, or a teacher or a librarian on that committee guiding us around how we put our dollars in line with [the foundation’s] principles or values?” he said.

Across the committees analyzed, there were a handful of academics, non-profit professionals, medical professionals and lawyers — but they were the anomalies amongst a majority of finance professionals.

Bolduc, for her part, would like to see more activists on investment committees, people with the skill sets, she said, to make an informed decision about the implications of investments. If a foundation is aiming to support Indigenous communities, she said, investing in fossil fuels or government bonds with shares in companies infringing on Indigenous rights, might not be aligned with mission and activists could help make sense of these decisions.

For Mark Sevestre, senior advisor for the Reconciliation and Responsible Investing initiative (RRII), it’s not necessarily finance expertise that’s the problem, but rather the particular type of finance teachings held by committee members.

“Up until now, with any kind of financial learning, the predominant point is to make as much money as possible,” he said. “That kind of philosophy has gotten us to the point where climate change is an issue, decent work is an issue, and [there’s] the exploitation of the environment and people just to make money.”

Through the RRII, Sevestre and his colleagues are working to support Indigenous and ally investors alike to select investments that contribute to protecting Indigenous rights and title. He’d like to see more committees adopt these approaches, and believes that a greater diversity of financial thought would help.

For Dennis Mitchell, an investment committee member with the Toronto Foundation, socio-economic diversity is just as important to consider as gender or racial diversity.

“I never hear anyone talk about bringing in someone who is poor, quite frankly,” he said. “[Or] someone who lives in subsidized housing, someone who is the recipient of the social impact investing that we do — those I think [are also] very important elements of diversity that very rarely get discussed or implemented.”

What’s preventing more diverse investment committees?

Becoming a committee member at a community foundation across the country isn’t easy. It’s not just a matter of sending along your resume or knocking on the foundation’s front door.

To join the board of directors at the Victoria Foundation, for instance, your candidacy has to be approved by a committee of bonafide community elites — the mayor of Victoria, a judge of Victoria’s supreme court, and the presidents of the local United Way, medical society and chamber of commerce.

A spokesperson for the Victoria Foundation noted however, that this is the last step in the foundation’s recruitment process — a process led by board and committee members, he said.

This process is not unique to the Victoria Foundation, however, and is rooted in historical tradition, said Hamilton Community Foundation’s Terry Cooke. “When [community foundations] were unknown, having judges or mayors on the board was seen as lending credibility to them as start-up operations,” he said. “And at the time, that was largely a successful strategy to get old money into the tent.

“But over time, what’s apparent is that the strategy has definite limitations in terms of how you reach more diverse parts of your community…[And] I think [now] you have to be intentional about how you get away from everybody drinking their own bathwater.”

(The Hamilton Community Foundation has moved away from this model, after several externally-conducted audits into diversity and inclusion over the past fifteen years, and based on a desire to increase the diversity of their board and committees).

Additional recruitment barriers persist elsewhere in the nomination process. At most foundations, over half of the committee are volunteers who are not board members — just volunteers appointed directly to the investment committee. Canada-wide however, this process is rarely public. At the Vancouver Foundation, for instance, investment committee members are mostly recruited by “word of mouth,” said Lee, with existing committee members, foundation staff, and board members playing key roles in recruitment.

This kind of approach limits who gets tapped to join these committees, says Sevestre. “They don’t go outside of their network of colleagues and friends — it’s people that they grew up with, or went to university with, or know socially,” he said.

And even with the motivation for change, increasing diversity on investment committees isn’t likely to happen overnight, barring committee dissolution and re-formation. At the Toronto Foundation and Vancouver Foundations, for instance, investment committee members can serve up to nine years. This allows for strong “continuity,” said Lee. But it also could limit the available spots for new joiners.

A bright spot on the horizon

Across the country however, the move toward impact investing at several community foundations appears to be contributing to an increase in committee diversity.

“We were an early champion of trying to align all of our assets with our mission through impact investing — and we made a fairly conscious decision in recruitment to see the benefit of people who weren’t in retail or institutional investment,” said Cooke, of the Hamilton Community Foundation. This strategy has resulted in the foundation having more women and people from non-finance backgrounds than any of the other nine foundations analyzed.

“Some of our very best impact investment and investment committee members are folks who are generalists and just bring different experiences to the table,” he said.

In January, the Kitchener Waterloo Community Foundation initiated a similar process, dissolving their “traditionally” constituted committee (with ten professionals from the finance industry) in order to make way for a new group with a broader range of expertise, said Tim Jackson, chair of the foundation’s investment committee.

The shift was prompted by the foundation’s new commitment to invest 100 percent of their assets using a socially responsible investment lens — and the recognition that they need new perspectives in order to make it happen.

“I may know what to ask from a financial standpoint, but I’m far from an environmental guru, so I don’t know if someone’s ‘BS’-ing me,” he said. As investors’ commitments to environmentally and socially responsible investing have grown, so too have asset managers’ capacity to understand and apply these concepts. Some are socially-rooted and others not, he said. “So [we’ll need] to have people who can ask the right questions, so that we’re not getting greenwashed.”

In the coming months, the foundation will grow their committee from the existing three-member “caretaking” group to a fully-constituted committee. The process will involve considerable outreach, he said, to ensure the foundation is able to benefit from new voices.

Methodology: How did we come up with the data?

Focus: We took a practical approach to our analysis, looking for broad trends in the diversity of investment committee members at public foundations. We narrowed our focus to the 15 community foundations with the greatest assets, using 2018 CRA data.

Step 1 — Analysis: Next, we collected the names of each of the 15 foundation’s investment committee members through foundation websites and annual reports and used publicly available information, including LinkedIn profiles, corporate postings, public profile photos, and other information, seeking to identify committee member’s race, gender and professional background.

Race was coded within four categories: white, Black, Indigenous, or racialized (non-Black, non-Indigenous). Indigenous status was included when it was stated in an individual’s biography.

Gender was grouped by: man, woman or other (e.g. Two Spirit, non-binary, genderqueer, etc.). ‘Other’ gender status was included when it was stated in an individual’s biography.

Professional background was categorized broadly by industry. Within the finance industry we included individuals who work in venture capital, private equity, family wealth management, banking, pensions, financial education, accounting, financial law or ‘high-finance’ business.

Step 2 — Confirmation: Last, we sent this information (excluding occupational data) to each of the 15 foundations, asking for confirmation of our analysis. Ten of the fifteen foundations confirmed our data, making small changes to our analyses of the membership of committees. Five foundations — the Vancouver Foundation, Winnipeg Foundation, Toronto Foundation, Victoria Foundation and Ottawa Community Foundation — confirmed the membership of their committees, but would not confirm racial or gender data.

The Victoria Foundation would not disclose racial and gender information “to respect the privacy” of committee members. At the Vancouver Foundation, diversity information was not shared with Future of Good, a representative said, because the foundation is engaged in an organization-wide diversity survey process and did not want to send investment committee members a separate request for information.