Funding shortfalls shutter Canada World Youth after more than 50 years

Why It Matters

The COVID-19 pandemic shut international borders and built silos at home. Programs that break down regional barriers and build international co-operation are needed now more than ever.

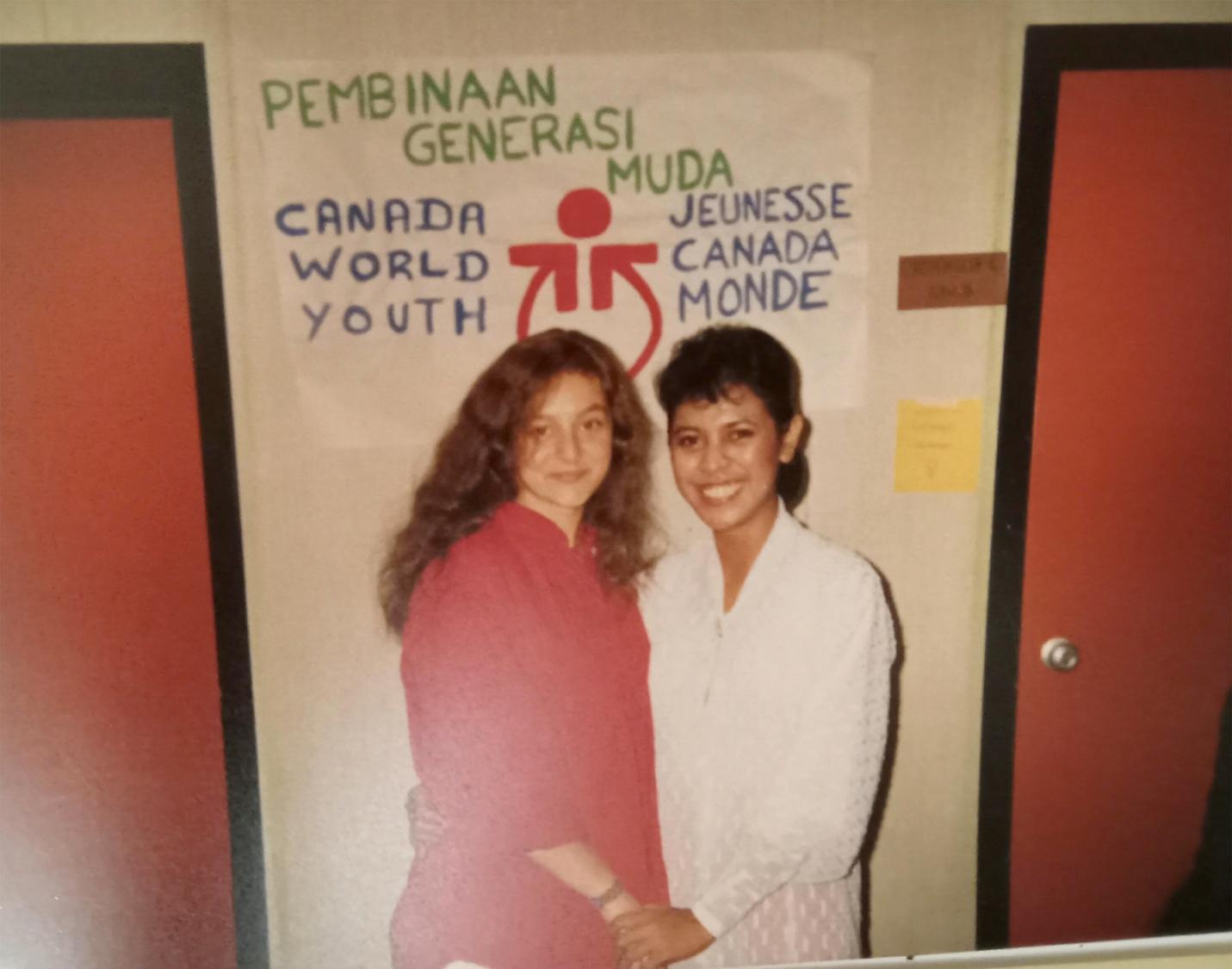

Viviane Schami and her Indonesian exchange counterpart, Ansye Sopacua, meet in Vancouver in 1988. Photo: Courtesy of Viviane Schami.

Viviane Schami and her Indonesian exchange counterpart, Ansye Sopacua, meet in Vancouver in 1988. Photo: Courtesy of Viviane Schami.

Viviane Schami was 20 years old when she boarded a plane for the first time; it was the fall of 1988 and the curious Quebecer was participating in a Canada World Youth program that would forever change her life.

“I was originally accepted to go to Pakistan, but they didn’t have enough participants there, so they said you’re going to Indonesia instead,” she said. “My life wouldn’t have unfolded the way it did if not for this program, this change.”

Schami met her Indonesian counterpart in British Columbia, where they lived and volunteered at a fruit packing co-op before heading to a rural community in Indonesia’s South Sulawesi province to volunteer with community organizations and learn about the regional culture. Experiences with her Indonesian host family, including the loss of a child, led her to a career in nursing and a lifelong interest in maternal health.

“It’s a huge disappointment that the youth of today won’t have this kind of opportunity,” she said.

After more than 50 years of building bridges at home and abroad, Canada World Youth is winding down its operations and will close its doors in the coming months. A statement posted on the charity’s website states “despite our best efforts to secure a stable future for the organization, we were unable to acquire the funding necessary to keep the doors open.”

President and CEO, Susan Handrigan, said that, while the news may seem sudden, problems began early in the pandemic as international programs were put on hold and the organization pivoted to virtual events.

“When we’re not doing programming externally, there are no funds coming in. So, we knew that we had a certain expiry date,” she said, adding they’d held onto hope the federal government would come through with funding over the summer months.

But, when September arrived without any of Canada World Youth’s programs receiving approval, Handrigan and the board of directors felt it was better to cease operations strategically and gradually, rather than hold out for a miracle.

“It allows us to be able to make sure that we take care of our employees,” she said. “I have some employees that have worked with me for 45 years, so we want to make sure they’re treated fairly. We also have partners around the world and we want to make sure that they’re treated fairly as well.”

But Handrigan continues to wonder why the Federal government discontinued its support of Canada World Youth, which was founded by Sen. Jacques Hébert in 1971.

In an emailed statement, Global Affairs Canada said the organization was welcome to apply for future funding, but that “recent Canada World Youth project proposals did not succeed in meeting pre-established selection criteria.”

Since 2000, the federal government has funded 17 international development projects implemented by Canada World Youth, amounting to more than $187 million “to increase the capacity of organizations across the globe to deliver sustainable poverty-reduction initiatives through youth volunteer and intern technical assistance.”

More than 40,000 youth from at least 70 countries, such as Yemen, Somalia, India and Ukraine, have participated in the organization’s reciprocal placement programs, which paired Canadian youth with international participants. Unlike many volunteer programs, Canada World Youth brought international youth to Canada, in addition to sending Canadians overseas.

The organization also worked to connect youth aged 15 to 25 across Canada, dismantling regional divides through conferences, youth-centered and gender-responsive training, environmental sustainability initiatives and other programming.

More recently, however, the federal government has moved towards so-called “innovative financing for global development.” Canada World Youth responded by creating “development impact bonds.”

“I’ll continue fighting until I can’t fight anymore — I’m an optimist for sure — but at the same time, I have to do what’s right for the organization and the employees, so I do have to follow our plan to close down our operations,” Handrigan said.

News of the impending closure hit the global Canada World Youth community hard. Thousands of past participants took to social media to share the impact the organization had in their lives and a petition calling on the federal and provincial governments to take action has garnered nearly 3,000 signatures.

Omar Morad couldn’t believe his eyes when he read that the organization, which sent him to Saskatchewan just a few months ago, was about to cease operations.

“I just copied it into Google translate to make sure I was reading what I thought I was reading,” Morad said. “This organization really doesn’t deserve that, I mean, I see the value of this organization in the future.”

Born in Palestine, a 21-year-old Morad arrived in New Brunswick via Lebanon and Syria in 2018. One year later, he founded the Union of Youth Newcomers and participated in Canada World Youth’s National Youth Leadership Summit in Saskatoon this spring, where he was able to learn about social and environmental issues across Canada, debate strategies for civic engagement and network with peers.

He also had the opportunity to learn about Indigenous people in Canada. Elder Mary Lee, from Pelican Lake Saskatchewan, opened the Summit with a prayer and participants visited Wanuskewin Heritage Park.

“Before, I heard people talk about Indigenous people, but now my respect is different … now it’s like I have a full understanding,” Morad said. “Now I know about all the challenges they go through, and I think it is good for newcomers to know this.”

“I just think it’s a really profound loss, not just to Canada, but to the global community,” said Krystal Bell, who took part in a six-month-long, trilateral youth leaders in action program in 2013, which saw participants work with organizations in Honduras, Nicaragua and Ontario.

Bell also participated in the International Aboriginal Youth Internships Initiative in 2015, spending four months partnering with an organization in Columbia. There, she focused on strategies for youth governance, building relationships and sharing experiences of colonialism, even participating in a sharing circle inside one of Columbia’s largest maximum security prisons.

“A lot of their programming is built around getting outside of your comfort zone and for myself, as an Indigenous youth, there aren’t that many opportunities to travel and have these types of experiences.”

Currently in her second year of studying child and youth care, with a focus on Indigenous families and youth justice, Bell said Canada World Youth helped her find the place where opportunity intersected with her passions and skills.

Back in Quebec, Viviane Schami occasionally provides translation services, having become fluent in Indonesian during her travels, which also lead to her conversion to Islam. Knowing the profound impact her experience had on her life, she had hoped her own two children — whose father she met in Indonesia — would be able to participate in a similar exchange.

“I used to tell my kids I’d love them to do Canada World Youth one day. They’re starting to have the urge to travel and see more of the world, now this isn’t available to them or anyone else, and that’s really too bad.”