Behind the scenes of a non-profit merger: preparing staff, funders and the CRA

Why It Matters

Charities and non-profits may find long-term sustainability challenging, given high delivery costs, fluctuating donation patterns, changing community needs, and shifting priorities for funders. One under-explored exit strategy is to merge operations with other organizations. Charities and non-profits, however, need to be aware of their obligations with the Canada Revenue Agency should they choose to go down this route.

In September, two non-profits providing digital skills education to underserved communities announced they would be merging their operations.

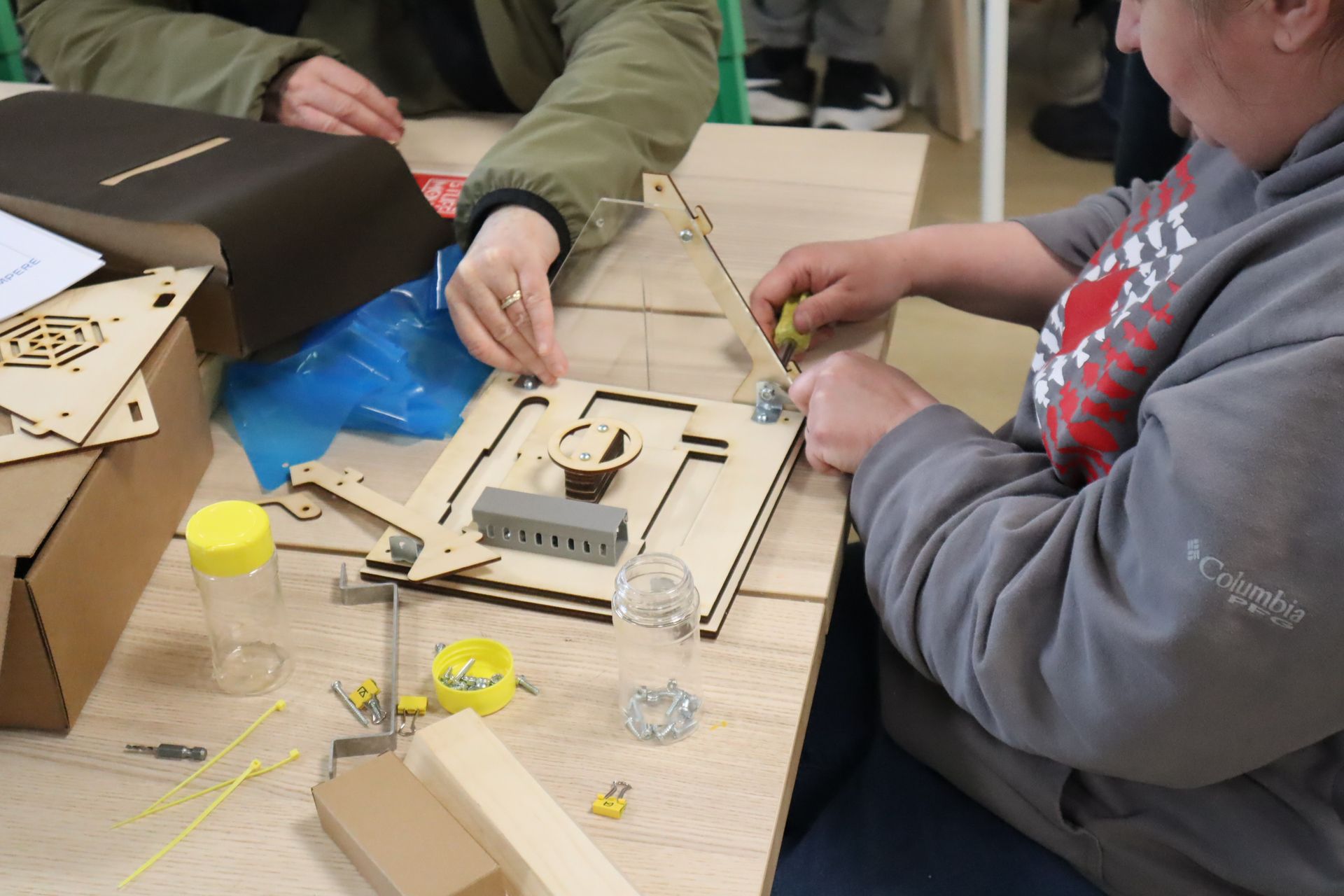

Formerly the Pinnguaq Association, Ampere runs science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics (STEAM) education programs, as well as several Makerspaces in Nunavut, New Brunswick, and the Kawartha Lakes region of Ontario.

Ampere will soon also run Canada Learning Code’s (CLC) programs, which focus on supporting people from low-income and marginalized communities to find roles in the technology sector.

CLC is a registered charity, while Ampere is a non-profit without charitable status. Having explored multiple routes to facilitate the acquisition, former CEO Melissa Sariffodeen explained that a “board recomposition” was the most straightforward method of merging the operations of both organizations.

To begin with, this meant that all but one member of the CLC board resigned, and Ampere’s board also became CLC’s board.

Going forward, Ampere and CLC will have separate boards and remain separate legal entities, said Ryan Oliver. Oliver will be serving as CEO of both Ampere and CLC after Sariffodeen announced she would be stepping down.

As well as programming, Ampere has acquired CLC’s intellectual property, branding and staff, Oliver said.

Is a merger / acquisition possible in the non-profit sector?

“This isn’t a merger in the corporate sense,” Oliver said. “First of all, there was no money exchanged.”

CLC was looking to combine forces with another organization after encountering what Sariffodeen felt was an “existential question” about their programs: Did they need to provide coding education when so much coding would now be done by artificial intelligence?

The charity put out a public call for expressions of interest from other organizations interested in merging operations.

“It became pretty clear that it was going to be an org that was larger than us to some degree that was going to absorb the programming of CLC and the team,” Sariffodeen said.

Both Ampere and CLC had a shared mission in providing digital and technical skills education to underserved communities. Ampere’s reach in the country’s northern territories could expand CLC’s program reach, Oliver felt.

CLC’s nine staff members would become part of Ampere, a non-profit with more than 100 staff.

Working around legal designations

Sariffodeen consulted many of her peers who had gone through mergers and acquisitions in for-profit contexts. Even some of the non-profits she spoke to have some experience with acquisitions or have equity stakes in businesses.

She found that very few charities had an appetite for merging operations, adding that she felt there would be “an immense amount of consolidation” in the sector.

The board recomposition route allowed for some continuity during the transition, but Sariffodeen also found other methods of merging operations.

“A non-profit could become a charity and then merge. We could [also] have wound down and dispersed our assets to a foundation.

“All of those things, though, didn’t feel like the best use of the capital and stewardship of the mission,” she said. It would also have been possible for CLC to make a grant of its own assets and its financial reserves, she added.

Charities and non-profits also have different obligations to the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), Sariffodeen pointed out. Now running both a non-profit and a charity, Oliver pointed out that the charity must stay within the mission it declares to the CRA. However, one organization can still support the operations, growth and funding of the other, he added.

“There is a piece to be careful about as I move those two things forward,” Oliver said. “Those separate boards have separate purposes and we [shouldn’t] have the charity stepping in the areas it shouldn’t be.

“It allows the non-profit to remain competitive and to remain looking for diverse revenue sources too, while the charity can really focus on ensuring that what we do in the non-profit is as cheap or no-cost as possible,” he said.