Canada makes “significant pledges” at COP15, announces Indigenous guardians network, but needs provincial buy-in to protect biodiversity

Why It Matters

One in five wild species in Canada is at risk of extinction. A strong, global commitment is needed to prevent the destruction of the world’s remaining biodiversity.

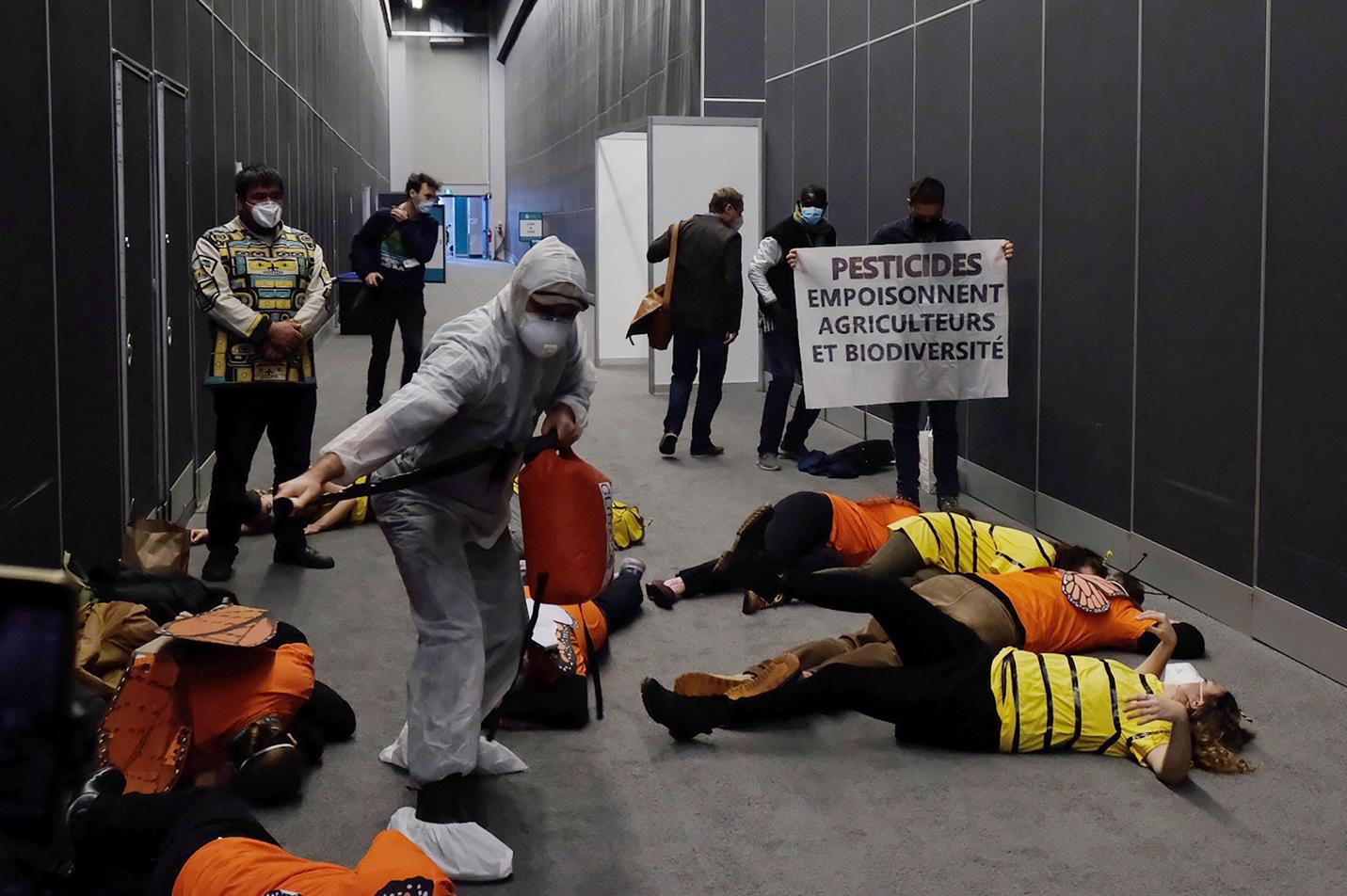

People dressed as bees and butterflies protest the presence of chemical companies at COP15. (Photo courtesy of the David Suzuki Foundation)

Big promises have been made at COP15, now Canadian climate and conservation organizations are watching to see if the Canadian Government follows through on its pledges.

The 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, better known as COP15, brought governments, businesses, conservationists and others to Montreal for two weeks in the hope of creating a new global biodiversity framework.

“The fight to protect nature has never been more important than it is right now,” said Steven Guilbeault, Minister of Environment and Climate Change. “With a million species at risk of extinction around the world, COP15 is a generational opportunity to work together to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.”

The Canadian government made several promises over the course of the convention, including the creation of the First Nations National Guardians Network that will support Indigenous-led environmental initiatives, although no dollar figure was assigned to the new agency, which builds on a previous program.

The federal government did, however, shed additional light on where the $5.3 billion it promised for climate action in June of 2021 will go, including $300 million to encourage non-governmental engagement in climate change programming in sub-Saharan Africa. Canada has also committed to protect 30 percent of land and water by 2030.

“I would say we’ve been pleased to see that our Canadian government has started to make some really significant pledges, especially around Indigenous-led conservation,” said Jay Ritchlin, director-general for nature and Western Canada at the David Suzuki Foundation. “We’re just really hoping to see those pledges become solid and actually followed through on.

Many activities currently impacting biodiversity are not controlled by Ottawa, but rather by provincial and territorial governments. Federal goals won’t meet protection targets without provincial buy-in, he said.

The national executive director for the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, better known as CPAWS, also believes Canada can only meet its ambitious biodiversity goals if all levels of government are onboard.

“It will only be achievable if provinces and territories step up their action, increase protected areas and support Indigenous-led protection initiatives,” said Sandra Schwartz.

Ottawa has been signing nature agreements with other levels of government, as well as making additional funding commitments. But not all provinces are onboard, Schwartz said. While Quebec has committed to increasing the number and size of its protected areas, Ontario has decided to strip its “greenbelt” of protected status.

The last time the world gathered to create a global framework for biodiversity was in 2011, setting 20 goals to be achieved by 2020. But in 2019, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Services estimated that only four of those targets would actually be met.

Describing herself as a “disappointed optimist,” Schwartz said more people are now paying attention to the issue of biodiversity and Indigenous-led protection. But she notes awareness doesn’t always equal action.

And while the Federal government has made many promises focused around Indigenous conservation, Ritchlin said they still have yet to live up to some basic commitments.

“We still have many, many reserves without clean drinking water. We still have pipelines being pushed through Indigenous territories without their consent and we still have logging of old growth that’s taking away hundreds of years of cultural knowledge,” he said. “So the rhetoric is good, and there’s some money on the table … but there’s still a lot that’s not going very well.”

Indigenous-led conservation has been a central theme in Montreal. Lakpa Nuri Sherpa, co-chair of the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity, was one of those who opened the conference, telling delegates that global citizens must see themselves as part of the natural world.

“As Indigenous Peoples, we have been custodians of our lands, territories and waters for millennia and have deep interaction with the ecosystems where we live. Evidence shows our lands are among the most biodiverse on the planet,” he said. “Only by recognizing the rights, knowledge, innovations, and values of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities will we be able to push forward the global agenda to sustainably use and conserve biodiversity.”

The disproportionate impact biodiversity loss has on the Global South is also on the minds of delegates. At The United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP27, in Egypt last month, a last-minute agreement promised loss and damage funding for developing countries impacted by climate-related disasters.

“The developing world is really looking to richer nations and saying, ‘well, you guys have really been a big part of this. What are you going do to help us?’” Ritchlin said. “And that’s still a big question.”

Developing countries walked out of COP15 at one point, but eventually returned to the negotiating table. By the end of the conference, nearly all of the 190 delegations present had agreed to protect 30 percent of land and water by 2030.

Participants also pledged a greater financial commitment to protecting biodiversity and a reduction in fossil fuel subsidies. Other key points in the agreement were aimed at improving equity, financial accountability and responsible consumption.

Nature Canada believes the Canadian government would have to invest $2.4 billion in international initiatives over the next four years to become a global biodiversity leader.

“One-off payments like that recently announced are great, but consistent annual funding is required. Around $600 million a year may sound like a lot, but it is peanuts compared to the $11 billion dollars Canada provides in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry each year,” the organization said in a press release.

Concerns have also been raised about the prominence of private sector interests at COP15. CropLife International, an industry association representing companies that make agricultural herbicides and pesticides, as well as plant biotechnology, has lobbied against proposed targets for pesticide reduction, but hosted an event for conference delegates.

“CropLife international has caused unimaginable damage to biodiversity around the globe. They’ve repeatedly lobbied for the status quo overuse and overreliance on toxic chemicals,” said Charlotte Dawe, conservation and policy campaigner for the Wilderness Committee. “They do not belong here and they should never have been given room to speak at COP15.”

Activists dressed and bees and butterflies protested in an attempt to draw attention to the issue. While there are nearly 16,000 official delegates, many more have travelled to Montreal for adjacent events, rallies, activism and gatherings.

“There is an amazing network of youth activists, Indigenous activists, civil society, and folks are really talking about how we change the whole mindset around the way our society operates,” Ritchlin said. “Being able to witness these folks, just putting it on the line, really caring and really deeply giving themselves to try and help heal the planet, has been the most energizing part.”

Schwartz said that more than ever before, people seem cognizant of how important biodiversity is and how much we’ve already lost. In Canada, 5,000 wild species are currently at risk of extinction.

“I remain hopeful that maybe, with more and more people paying attention to what’s happening, to species extinction, to the destruction of nature, that change will come,” said Schwartz. “The bottom line is that we need nature to survive … we simply do not have time to continue waiting for nations to step up.”