Charities aren’t ready for social finance — here’s how they could be

Why It Matters

Social finance could help charities support Canada’s COVID-19 recovery and become sustainable, but many are not ready for investment. Two-thirds of charities don’t even know what it is. Having lost billions in revenue, charities cannot afford to miss out on new sources of income.

In St John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, the charity First Light has been trying its hand in business. In recent years it has established five social enterprises, from a childcare centre to an Indigenous cultural training program. From April to August last year its businesses accounted for 38.9 percent of the charity’s income.

“There was a point in time where we were reliant completely on government funding,” says Stacey Howse, director of programs at First Light, which was formerly the St John’s Native Friendship Centre. Relying more on their own income has helped them make longer-term plans and led to lower staff turnover, she says, while creating positive social impacts.

As Canadian charities look to recover from billions in lost revenue, while contributing to the country’s recovery efforts, more are turning towards social finance.

Having long been completely reliant on grants from foundations and governments, charities are looking to generate their own income – usually by establishing social enterprises that can turn a profit. Social finance investments can be vital in helping those enterprises grow.

However, according to a new report released by Imagine Canada, most charities are much further behind for-profit social enterprises. In the first survey of its kind, the report showed that most charities are not “investment ready” – meaning they would be unable to acquire and repay social finance investments.

The federal government wants investment ready projects for its upcoming $755-million Social Finance Fund and launched a $50-million Investment Readiness Program (IRP) last year to give charities and other organizations tools to prepare, such as conducting research or getting business development advice. But Imagine Canada’s new report has laid bare just how much more work is needed.

Charities aren’t aware of social finance, especially at the community level

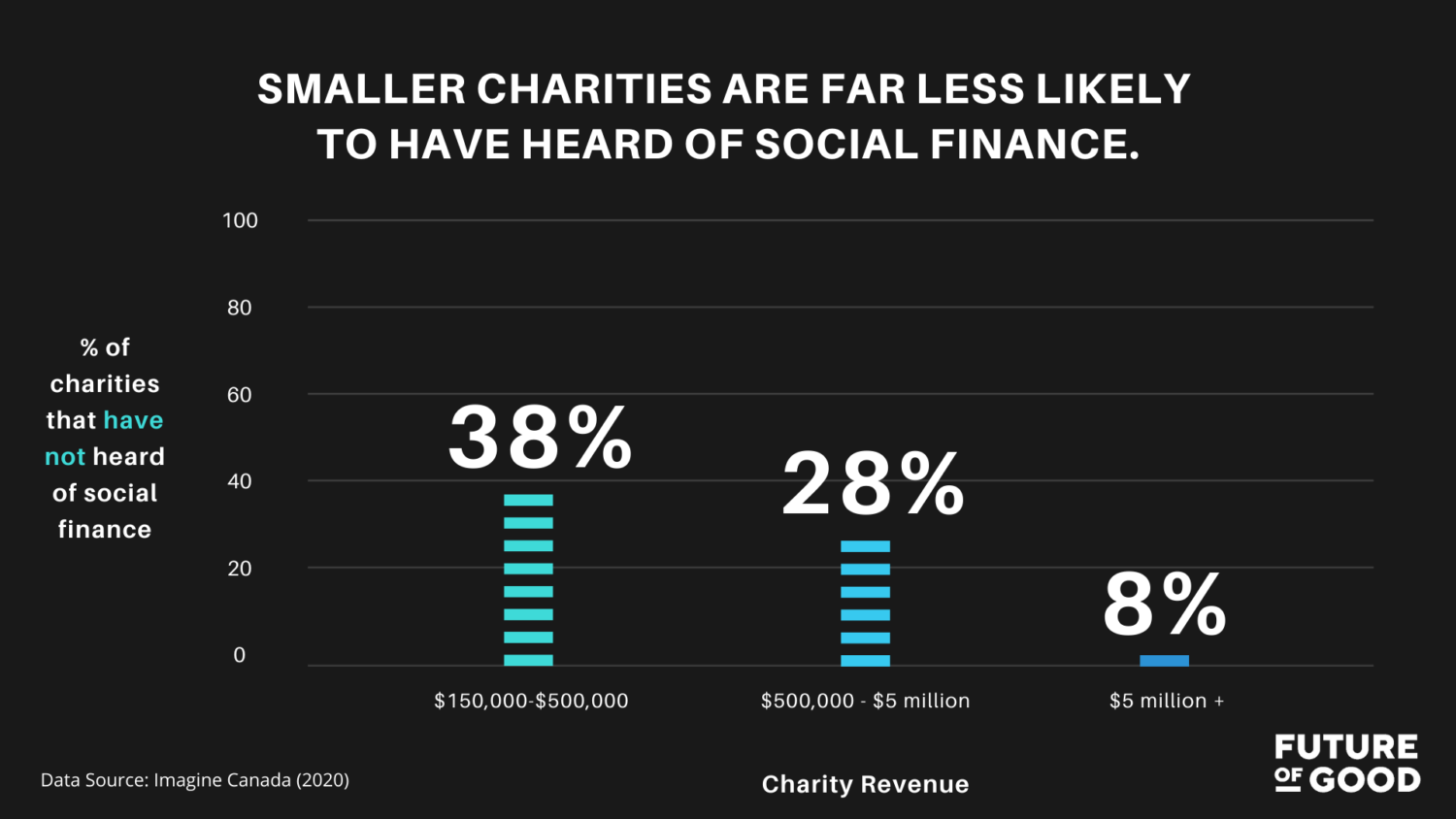

The first challenge is that charities simply aren’t aware of social finance. The survey of 1,018 charities – weighted to be representative of charities nationwide – found that two-thirds don’t know what it is, and half of those charities have never even heard the term.

Digging deeper, however, the survey shows an area where the awareness gap needs addressing the most.

Smaller charities are far less likely to have heard of social finance: for those with revenues between $150,000 and $500,000, 38 percent were not at all familiar, compared to 28 percent between $500,000 and $5 million, and only 8 percent for charities of $5 million or more.

Meanwhile, only 60 percent of charities serving smaller geographic areas like municipalities were familiar with social finance, compared to 88 percent of those working across provinces and territories. Certain sectors are also much less aware of social finance, including “arts, culture & recreation,” health, and social services.

The findings suggest that the government and organizations across the social impact sector need to work collaboratively to communicate social finance in a more accessible way, says Adam Jog, manager of public policy & research at Imagine Canada who authored the report.

This includes things like simplifying terminology, being clear about why charities would want to engage with social finance in their context, and identifying champions in a community’s target audience to spread the message, he says.

One potentially powerful tool could be spreading more case studies of social finance’s use in the charitable sector. Though not published in the report, Jog told Future of Good that when asked what kind of information would be helpful to charities, dozens suggested that examples of similar organizations that have taken on social finance would be a useful tool.

Investment readiness means embracing risk — an unfamiliar mindset for many charities

In the Imagine Canada report, charities highlighted several potential barriers to seeking a social finance loan. The barriers most commonly mentioned included concerns about their ability to repay a loan (identified by 23 percent of charities), or that their board might not approve (21 percent).

Though largely financial, these concerns point to the difference in mindset between a charity and a business. Charities were not designed to create a profit or take risks – such as by taking on debt – but social finance necessitates doing both.

“Our sector is very averse to having debt,” says Angela Carter, executive director of Roots Community Services, a small charity in Brampton, Ontario. Roots was recently awarded a roughly $19,000 grant through Community Foundations Canada as part of the IRP, which it’s using for a feasibility study into creating a social enterprise incubator for marginalized and racialized women entrepreneurs.

Hailing from a finance background herself, Carter says charities need a business-minded board and leadership in order to be willing to take risks associated with social finance. She says her organization is still only testing the water with the feasibility study, and she would need to convince her board to go forward with a loan.

IRP participants range from charities like Roots, exploring early business ideas, to organizations with more developed plans. “The point [of the IRP] is not just to push everybody forward, come hell or high water,” says Sara Lyons, vice president of Community Foundations of Canada. Instead, she says, it can help charities to explore whether it’s the right direction for their organization. For small charities without any earned income, for example, it may not be appropriate to take on loans and investments.

Many charities lack the organizational capacity, especially after COVID-19

Charities also need to have the right organizational capacities to be ready for social finance investments. In the survey, which was conducted before COVID-19 took hold in Canada, charities were asked to rate certain capacities as strengths or weaknesses, independent of social finance projects.

Across five different domains, there were two capacity areas that stood out as the weakest: financial capacities, such as the ability to raise funds, and impact measurement and evaluation. For example, more than one-third of charities listed the ability to collect data in order to evaluate their work as a weakness.

Measuring impact and managing finances are two key aspects of social finance, which suggests that human capital is needed for charities to become investment ready. In the previous question on barriers, one in five respondents identified “lack of staff/volunteers with the right skills/experience.”

Shady Hafez, special projects advisor at the National Association of Friendship Centres – which is distributing $1.12 million in IRP money to friendship centres across Canada – says that COVID-19 may have made this capacity issue even more significant for charities considering social finance.

According to Imagine Canada research released in May, the pandemic has led to decreased organizational capacity for approximately 40 percent of charities, and 30 percent of charities had already laid off staff members as their revenues suddenly dropped.

By exploring social finance, organizations “now have to divert energies away from your regular programs and services that your centre is designed to do,” Hafez explains, many of which are now in higher demand post-pandemic, “and then invest that time and energy into something that’s very new, something that could be risky.”

Hafez says it can be helpful for organizations to have dedicated staff overseeing projects who have expertise in social finance, which suggests much more philanthropic or government funding may be needed for more charities to build the necessary capacity. First Light, for example, has a business department that works closely with the operations team.

Closing the gaps

For the federal government and its partners, the size of the gap between many charities and investment readiness suggests that the two-year, $50-million IRP pilot program should be expanded both in terms of money and time.

A two-year time frame also isn’t enough for charities to become informed about social finance, decide whether it’s appropriate for them, and to take the necessary steps towards implementation, says Adam Jog. “If social finance is to live up to its promises,” he says, “eventually there does need to be a concerted effort to involve a larger number of charities in this sort of initiative.”