Community organizations warn more people with disabilities could choose medically assisted death in the face of inflation and “legislated poverty”

Why It Matters

More than 6.2 million Canadians live with a disability, putting them at a greater risk of living in poverty. Meanwhile, two thirds of organizations serving those with disabilities are at risk of closing down in the next three years.

Inflation has many Canadians making tough decisions about affordability, but for some of those living with disabilities, rising costs are leading to homelessness, poverty, hunger and — in some cases — death.

“There are people choosing (medical assistance in dying) right now, this is actually happening,” says Victoria Levack, an advocate with The Disability Rights Coalition of Nova Scotia. “Because they don’t have access to housing or supports.”

Last spring, a 51-year-old Ontario woman died with medical assistance after being unable to find affordable housing that met her medical needs. A few months later, Winnipegger Sathya Kovoc chose a medically assisted death, not because she’d been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but because she was unable to access adequate home care.

In her own obituary, Kovac wrote “it was not a genetic disease that took me out, it was a system.”

Dr. Naheed Dosani, a palliative care specialist at St Michael’s Hospital at Unity Health Toronto, is on the frontlines and says the affordability crisis has cut the thread many people already experiencing structural vulnerabilities, such as disability, poverty and racism, were holding on by.

“We have many examples now, from coast-to-coast, of people with disabilities who are choosing medical assistance in dying, not because they want to die, but because they do not have access to the resources they need to live well,” he says. “I work in a world where it’s possible to successfully arrange for MAiD in two weeks … yet it takes years to get the people I care for into housing, months to get folks income supports and weeks to get mental health and harm reduction treatments.”

It took Levack 10 years — and a lawsuit — to finally force the Government of Nova Scotia to begin providing adequate housing for her and other young people living with disabilities. After a decade of being “incarcerated” in a seniors’ home, where she was assaulted by other residents suffering from dementia, she said it’s a relief to now reside in the community as part of a new pilot program operated by Independent Living.

“I’m lucky my bills are covered … I don’t have to worry about heat or lights or any of that. Like, I’ve never seen those bills,” she says. “But lots of disabled people don’t have that, they are choosing between heat and food and rent right now. There’s people eating one meal a day and people who can’t afford medication.”

Rising costs have also hit service providers working within the disability community especially hard. They are seeing an increased demand for services and programs at a time when inflation has devalued their funding and hiked operating expenses.

“It’s getting to a really critical point,” says Andrea Hesse, CEO of The Alberta Council of Disability Services. “Funding has not increased, either for direct or indirect costs to these organizations, and they’re heavily reliant on the funding that flows from government.”

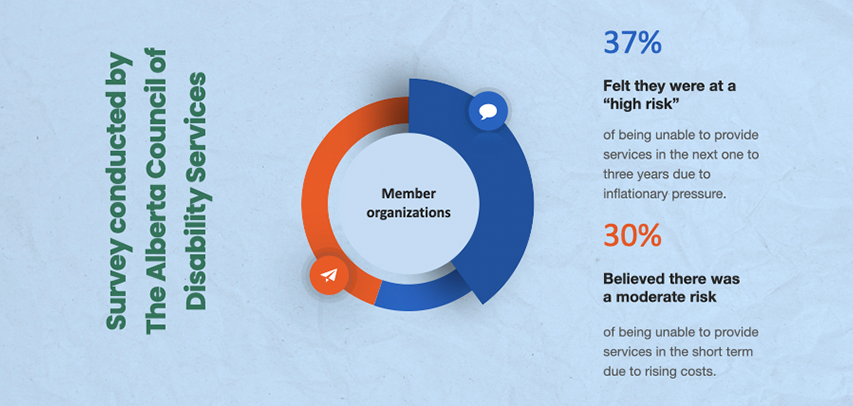

Member organizations have told her their ability to deliver services is at risk.

A survey conducted by the organization last year revealed 37 per cent of disability service providers felt they were at a “high risk” of being unable to provide services in the next one to three years due to inflationary pressure. Another 30 per cent of respondents believed there was a moderate risk of being unable to provide services in the short term due to rising costs.

“Administrative costs, like insurance, maintenance and utilities … are going up significantly, but no new funding is coming in; people are having to pull money out of services that would normally go to direct support to individuals in order to maintain those costs,” Hesse says. Stagnant wages, combined with a higher cost of living, has also exacerbated staff retention issues, she adds.

“Many organizations are just trying to keep the lights on,” says Hesse.

Non-profit organizations across Canada often provide Government mandated and funded programming, but are expected to do it at unreasonably low costs, say those working in the sector. Organizations often rely on donations to fill gaps in government funding.

“Programs are funded by the government, but that funding has not kept pace with cost of living increases historically, never mind during this recent hike,” says Margo Powell, executive director of Abilities Manitoba, which represents a network of agencies serving people with intellectual disabilities.

“We’ve gone back and tracked this since the year 2000 and funding has lagged behind cost of living increases, by upwards of 33 per cent.”

That’s resulted in many organizations working with “skeleton crews,” while also changing how they deliver services. In some cases, that means a reduction in programming, Powell says, adding the most significant impacts are seen at the support staff level.

“They’re the direct support professionals, so their wages are determined by government funding, which hasn’t increased,” she says. “But the work that people do in our sector is becoming minimum wage work, even though the skill set required is very complex — it is not minimum wage work to support someone in every area of their life.”

One organization represented by the agency has a current turnover rate of 450 per cent, says Powell. Many people who want to work as support workers end up leaving the profession because they simply can’t afford to make ends meet on the wages they’re offered.

“Can you imagine you need someone to help you have a bath and you have upwards of 18 different people in like three months?” she says. “It’s so devaluing.”

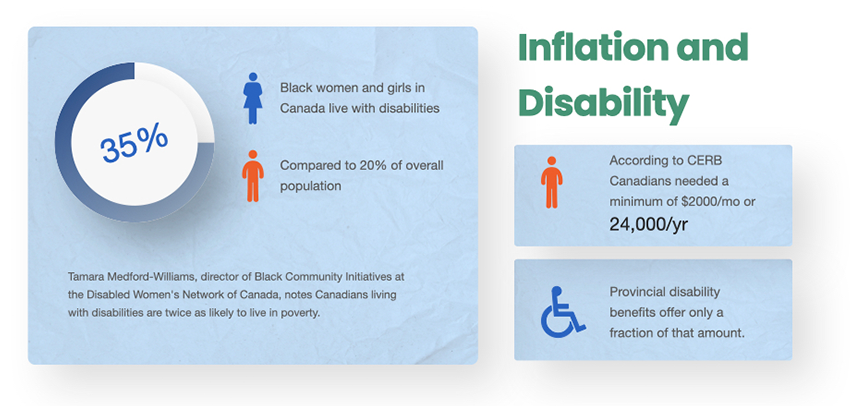

Tamara Medford-Williams, director of Black Community Initiatives at the Disabled Women’s Network of Canada, notes Canadians living with disabilities are twice as likely to live in poverty.

“And because poverty coincides with other intersecting forms of systemic oppression like race, gender, ability, sexual orientation and expression … that makes the issue of inflation and rising cost of living much more critical for those with disabilities,” Medford-Williams says.

Nearly 35 per cent of Black women and girls in Canada are living with disabilities, compared to about 20 per cent of the overall population, she adds, making them particularly susceptible to rising costs.

“With the issues of racial inequality and systemic oppression, Black women and girls with disabilities really face a plethora of systemic barriers,” says Medford-Williams. Inadequate and restrictive social assistance rates, along with wage disparities related to race, gender and ability, further compound issues around poverty, housing and food security, she adds.

Women, particularly Black or otherwise racialized women, are often dependent on their partners or other family members for care in the face of unreasonably low welfare rates, putting them at an increased risk of physical, mental, sexual and financial abuse, Medford-Williams says. Gender-based violence is almost three times higher for women with disabilities, she adds.

Financial autonomy would lessen those risks, but inflation is only pushing independence farther out of reach for many Canadians with disabilities.

During the pandemic, the Canada Emergency Response Benefit or CERB, posited that every Canadian needed a minimum of $2,000 to live on each month or $24,000 per year. And yet, provincial disability benefits offer only a fraction of that amount.

In 2021, a single person living on a disability allowance in New Brunswick could expect to receive $859 per month or about $10,298 for the year. In Ontario, a single person with a disability could expect about $15,449 per year.

“I can only imagine, with the situation being exacerbated because of the rising costs of living and inflation, that more individuals living with disabilities will apply for MAiD,” Medford-Williams says.

Levack says it may take generational change to shift the dialogue around disability, something that won’t happen fast enough to address the current affordability crisis. Political will to address the issue is also in short supply, she adds, noting ableism continues to be deeply embedded in Canadian policy and Canadian society.

“Capitalism is really to blame,” says Levack. “Governments view citizens as either productive or unproductive … so if we’re seen as a drain on the system, it’s easier to kill us.”

Too often, disability policy fails to centre the individuals who are actually affected, Dosani says.

“I feel like people with disabilities, particularly those who are experiencing poverty, are not being heard,” he says. “And I think if we really actually centered the voices of the people who are being most impacted … this would lead to new and innovative solutions to deal with some of these issues.”

The federal government has introduced Canada Disability Benefit Act, or Bill C-22, which would create the first tax-free, guaranteed income supplement for working-age Canadians with disabilities, but it has yet to pass the Senate.

Advocates are cautiously optimistic about Bill C-22, but say there are many unanswered questions, including who will be eligible and if provinces will claw-back their own disability benefits in response.

Reducing stigma and awareness around social assistance would also help, Dosani says, particularly educating the public about what assistance actually covers.

“Many people in Canada think that social assistance rates provide enough for people to live on and that’s the furthest thing from the truth. In fact, social assistance rates are so low that they actually place people living with disabilities below the poverty line,” he says. “It is essentially legislated poverty.”