Nature Investment Hub hopes to generate $20B for natural land conservation and restoration in Canada

Why It Matters

In 2022, the United Nations adopted the first multilaterally agreed definition of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS). This December will see Cop 28, the international conference to assess progress on the 2015 Paris Agreement goals to combat climate change. It will include the launch of the first State of NBS report. NBS can save more CO2 annually than the emissions from the entire global transportation sector and reduce the intensity of climate hazards by 26 per cent.

Courtney Kehoe says her core values, earned through 15 years of fishing lobster off the Nova Scotia coast, sustain her as the managing director of a new investment hub.

Those core values are what inspired Courtney to join the team behind the newly launched Nature Investment Hub, which aims to contribute to a five-fold increase (equivalent to $20 billion) in public and private investment in the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of nature in Canada.

“Government and philanthropic funding provide the bulk of finance in nature and nature activities. They can increase that amount, but it will never be sufficient,” says Kehoe.

The Nature Investment Hub intends to get in a room with all stakeholders with expertise and power to create nature financing initiatives.

What is the difference between climate finance and investment in nature?

“Investing in climate would be building resiliency within our economy and mitigate the risk (of climate change),” says Kehoe. “Investing in energy transition, clean technology, and all initiatives toward net-zero emissions classify as climate investment.”

“Investing in nature includes financing conservation and restoration activities across the country,” she says. But it also includes projects improving wetlands to reduce the pressure on municipal water treatment systems and innovative farming practices supporting biodiversity and greater productivity.

Nature-based solutions can be implemented in cities, too, says Kehoe. Some examples of this already happening in cities include flood control and heat island reduction initiatives.

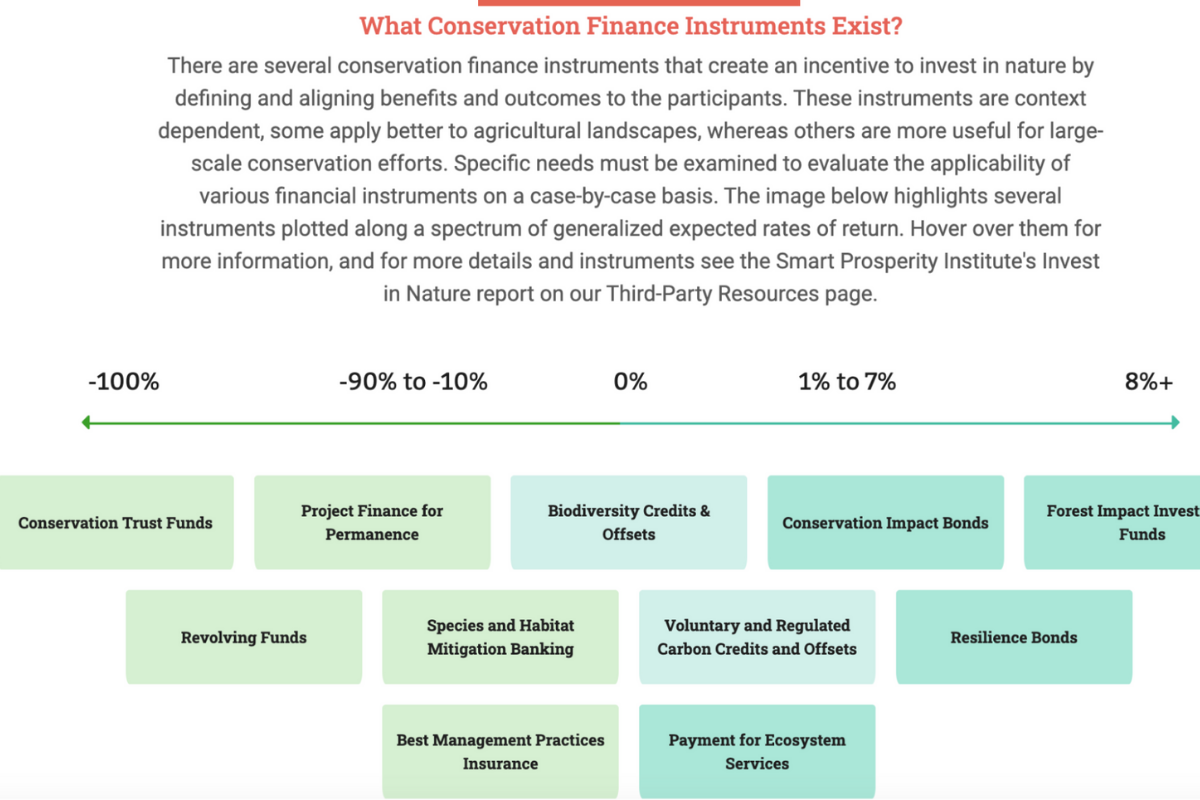

The Nature Investment Hub is a conservation finance initiative partnered by The Natural Step Canada and the Smart Prosperity Institute. Conservation finance uses financial instruments to generate, manage or deploy capital – or align incentives – to achieve nature-positive outcomes.

Where do financial returns on investing in nature come from?

“It could be from direct revenue generation from a commodity produced, like a forest or agricultural product,” says Kehoe.

“It could also stem from reduced insurance premium payments due to investments in natural infrastructures. (Financial) returns could also be avoided capital or maintenance costs, like the water treatment example. And in certain regions, revenues from off-set or carbon credits.”

An example of a nature-based solution is the Guardians Program

“It is important that we ensure Indigenous Nations’ aspirations and visions are at the centre of a conservation economy in Canada,” says Kehoe.

To illustrate this vision, she gives the example of the Guardian Network, a worldwide initiative.

“These programs do wonders for the conservation of nature while strengthening Nationhood, creating economic opportunities and improving the wellbeing within Indigenous communities,” says Kehoe.

As detailed in a report by the Environmental Law Center of the University of Victoria, “Guardians monitor the activities of resources users, enforce federal, provincial, and Indigenous laws, gather data on the ecological health and wellbeing of traditional territories, compile data to inform Nation resource decision making, and engage in community outreach and education about conservation of cultural and natural resources.”

The report monitored 70 Guardians and Guardian-types programs worldwide, highlighting the benefits for both First Nations and society.

These benefits include “a better conservation of natural resources, restoration of damaged fisheries, forests and streams, key jobs in rural communities, improvements in community nutrition and health, and enhancement of the Reconciliation relationship that is essential for long-term economic prosperity.”

According to the report, the return on investment in Guardians programs can range from $2.5 for each dollar spent to $10 to 1.

A Canadian example: Nunavut Aviqtuuq Guardians

A September 2023 report from the Smart Prosperity Institute (SPI) concludes that in Nunavut, co-benefits from investments in the Aviqtuuq Guardians are estimated to have generated $12 million since 2016.

Nunavut is home to the fastest-growing natural resource extraction industry in Canada. Still, the extractive economy has proven detrimental to the health and the population’s environment, according to the report’s authors.

The SPI report highlights the community’s struggle to access nutritious food, the lack of local job opportunities, and the loss of the Inuit language and culture.

The Taloyoak community proposes developing an Inuit-led protected and conserved area in the Aviqtuuq Peninsula. The Guardians Program is part of this conservation economy initiative, which aims to create local jobs and protect the environment.

Taloyoak hopes to help achieve food sovereignty and develop local tourism infrastructure, as told by the community leaders to the Smart Prosperity research team, who visited Taloyoak in January 2023.

The Guardians will use smartphones to collect data and document changes in the landscape, including the migration patterns of key land and marine species and the growing impacts of climate change. If a sufficient database is created, the long-term project could inform decision-making around conservation.

The support of Indigenous-led conservation and stewardship was an essential factor during the consultations leading to the creation of the Hub, says Kehoe, as was the importance of compelling storytelling.

“We need to get better at telling conservative finance stories integrating economic returns. We need more Canadian examples,” says Kehoe.

The Hub will also work to mitigate the risk of these investments, says Kehoe.

“We must provide evidence so the private sector can open its eyes to the risk and accept it. We can also structure these investments in a way so that multiple partners are involved – a term called blended finance – allowing government funding to leverage and catalyze private investment.”

Between 2018 and 2022, the Canadian government funded 80 Guardian Programs.

Aside from directly funding nature-based solutions, governments can create financial tools to attract impact investing

Conservation impact bonds are an example, and Canada piloted the Deshkan Ziibi Conservation Impact Bond to attract investment.

The Ontario project netted $130,000 in impact investments from Verge Capital, offering a five per cent interest rate repayable in three years.

What are particular challenges for a Canadian conservative finance ecosystem?

“Canada’s land ownership structure is different from the U.S. and many other countries,” says Kehoe.

In Canada, 90 per cent of the land is Crown land, but in the U.S., 60 per cent is private.

This means it’s not usually possible for private-sector donors to own nature-based projects in perpetuity, says Kehoe, a disadvantage when investors want assurance their donation will have a lasting impact.

Another challenge is the tension between different jurisdictions responsible for natural resources. The federal government sets targets and commitments, but the provinces have jurisdiction to make decisions over wildland use.

“The Hub will convene the right people to overcome the challenges and to build the business case for investing in nature,” says Kehoe.

“It is important to stress that conservation finance does not redirect donors towards investing. It should create new investing opportunities for new donors.”