The shadow side of the rise of big hospital foundation gifts: donation disparities, roller-coaster giving and donor influence

Why It Matters

If COVID taught us anything it’s this: we need our healthcare system. And yet, Ontario’s current funding policy for capital projects — rebuilding old ambulance bays, purchasing MRI machines, and building new wings — relies, in part, on philanthropy. Some experts say that this leaves the system vulnerable to health disparities.

This journalism is made possible by the Future of Good editorial fellowship covering the social impact world’s rapidly changing funding models, supported by Future of Good, Community Foundations of Canada, and United Way Centraide Canada. See our editorial ethics and standards here.

In late June, under a hot sun, Aatif Baskanderi spoke to an assembled crowd of nurses, doctors, and hospital foundation staff in Scarborough, Ontario, on the territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Anishnabeg, Chippewa, Haudenosaunee and the Wendat. He was all smiles. It was a historic day. Baskanderi, the CEO of the Northpine Foundation, was there to announce a donation of $20 million dollars — the largest gift the Scarborough Health Network Foundation has ever received.

After his speech, as he milled about, the manager of the emergency department of one of the region’s three hospitals approached him. “I never thought I would see something like this,” Baskanderi recalls her saying. When it comes to big donations, he says, hospitals in Scarborough have often been overlooked.

Scarborough occupies Toronto’s southeastern corner, beloved by residents for Vietnamese pho, Indian butter chicken, Jamaican patties, and other culinary delights, its rugged shoreline across Lake Ontario, and its diversity — 59 percent of residents are new Canadians and 74 percent are racialized people.

But despite the area’s many strengths, ensuring health equity in this part of the city is a challenge. Though Scarborough’s three hospitals serve more than 25 percent of the city’s population, and some of Toronto’s patients with the greatest needs — they bring in less than 1 percent of the region’s hospital donations, according to Scarborough Health Network Foundation.

Healthcare is a provincial responsibility, but Ontario health policy implicitly relies on philanthropic funding. Current provincial policy asks local communities to cover as much as 30 percent of the total costs required for hospital upgrades, according to the Association of Municipalities Ontario. Communities must contribute 10 percent of the cost of capital projects, like rebuilding an ambulance bay or remodelling an emergency room, and 100 percent of the cost for all equipment, furniture and fixtures, including X-rays, CT scanners, and more.

This is pricey stuff. The total capital budget for the refurbishment of Scarborough’s three hospitals, for instance, is north of $1 billion. This puts the community’s “local share” at more than 100 million dollars.

“Local share” funds can be raised through parking and other hospital fees. They can be provided by the municipality. They can also be financed by philanthropy.

Propelled both by generosity and accumulating wealth, Canadian philanthropists, like the Northpine Foundation, have been increasingly stepping up with mega-gifts for hospital campaigns like these. New research from consulting firm KCI shows that in 2021, the number of gifts of over $500,000 to Canadian hospital foundations hit a ten-year high. KCI tracked 96 such gifts in 2021, totalling $412 million.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Health said, by email, the local share policy “assists to ensure community interest and participation in the planning of hospitals and in controlling costs during design and construction.” But several health funding experts who spoke with Future of Good say that relying on philanthropy to help cover the cost of hospital upgrades puts less well-off communities, like Scarborough, and many rural communities, at a disadvantage.

“I live in northern Ontario,” says MPP France Gélinas (Nickel Belt), the NDP’s most recent health critic. “The small hospitals in Mindemoya, in Iroquoi Falls, in Smooth Rock, in Elliot Lake…their needs are huge and their chances of attracting a $20 million donation are zero.

“Thank you to those donors for answering this call,” she says, “but this is not how our health system will deliver equity in care. Because those type of donations are not available to all.”

For communities who can’t attract mega-gifts, like Northpine’s donation to the Scarborough Health Network Foundation, some experts say it’s cash-strapped municipal governments and their taxpayers who have to foot the bill. And for those who are better able to attract such donations, concerns remain too, chiefly that this approach to capital funding subjects hospitals to fluctuations in donations and can give wealthy donors a greater say in public healthcare.

Rural concern about capacity to raise “local share”

This winter, more than half a dozen communities across Ontario’s Almaguin Highlands passed parallel resolutions. In them, small-town councillors called on the Provincial government to re-examine the “local share” policy to “better reflect the limited fiscal capacity of municipalities and the contributions to health care services they already provide.”

For many in southern Ontario’s cities, the Almaguin Highlands is cottage country. Gray-black rock of the Canadian shield juts out, the grass grows wild, and freshwater lakes abound. But for about 24,000 people, this region is home year-round. Rod Ward, the chair of the Almaguin Highlands Health Council, is one of them.

A couple of years back, Ward got word that his community’s two local hospitals, in Huntsville and Bracebridge, would either be rebuilt or refurbished to bring them up to modern standards. He was thrilled, knowing the hospitals needed the overhaul; but concerned about how his and other Almaguin Highlands communities would pay for it.

Though the capital campaign for the rebuild of both hospitals is not yet underway, the latest estimate, Ward says, is that it’ll cost about $600 million. This means that local communities could be on the hook for a local share of about $60 million.

But unlike downtown Toronto, where corporations and deep-pocketed philanthropists often provide large donations to help cover a large portion of the local share, Ward doesn’t believe such gifts will be forthcoming in his region.

“There are a few larger businesses in the Muskoka area, but they’re not typically going to be people who are going to hand over tens of millions of dollars as some kind of donation,” he says. “We could get lucky. It could happen. But it just doesn’t seem— it’s not something we would want to count on.”

Ward says municipalities, both rural and urban, tend to save some money for major hospital upgrades. That’s been the case in Armour Township, population 1,500 or so, where Ward is a councillor. “[But] we’re talking about a few thousand dollars, not hundreds of thousands of dollars,” he says.

His biggest concern is that if the region isn’t able to attract enough donors, it’ll be the residents of the region, including his own in Armour, who have to cover the cost of the local share through a municipal tax levy. “That’s a concern, because, first of all the low population,” he says, “and second of all, it’s also economically at the lower end of the scale for most of the region.”

In Armour, the median household income is about $60,000 — about 20 percent lower than the provincial average, according to data from the 2016 census. Ward says an increase in taxes to cover their portion of the local share for the hospital rebuild would be a “huge deal” for Armour residents who are low-income, especially during a period of record-high inflation.

Dr. David Klein, a physician at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a professor of public health at the University of Toronto, says it’s not just residents of Armour who face this challenge.

“There are clearly have and have-not hospitals and regions in the province of Ontario in terms of their ability to fundraise, their infrastructure to fundraise, and the population that they’re fundraising from,” he says. “And so ultimately any sort of sharing arrangement [between the Province and local communities] can only further exacerbate the health equity challenges that come with being in the have-nots.

“If you’re a small hospital in Fenelon Falls, trying to compete with SickKids or Princess Margaret to get that 10 percent or 30 percent for your capital projects, that’s not a fair fight,” he says.

The Ministry of Health, however, disputes that the local share policy disadvantages smaller communities. A ministry spokesperson said, by email, “the size and cost of hospital projects are proportional to the size of communities, as hospital planning for bed numbers and ambulatory services are based on local needs, defined by demographics and population projections.”

Gélinas says, however, that construction is more costly in Northern Ontario, with higher costs of transportation, labour and materials. Two reports on relative cost of road construction and manufacturing in Northern Ontario compared to Southern Ontario suggest this to be the case.

She also underscores that residents in these communities have less capacity to make big donations to hospitals. In 2013, a greater proportion of rural Ontarians donated to charity than their urban neighbours (91 percent vs. 84 percent), but on average, gave less ($534 vs. approx. $550), according to Statistics Canada data, analyzed by the Rural Ontario Institute.

Though no comprehensive studies have analysed the distribution of hospital donations across the province, anecdotal data can offer some clues.

In 2020, the University Health Network Foundation, which fundraises for four Toronto area healthcare institutions, including Toronto General Hospital, received 24 gifts of over $500,000, including from several large private foundations, including a $8.5 million donation from the Peter and Melanie Munk Charitable Foundation, according to data from the Canada Revenue Agency, accessed via CharityData.ca.

In the same year, SickKids Hospital and its foundation received 18 donations of more than $500,000, including donations of about $11.5 million from the Peter Gilgan Foundation, $6.3 million from the Rogers Foundation, and $5 million from the FDC Foundation.

In stark contrast, in this same year, the largest donations to Rod Ward’s two regional hospital foundations, the Huntsville District Memorial Hospital Foundation and the South Muskoka Hospital Foundation’s top donations were $100,000 and $125,000 respectively, from a pair of Toronto-based family foundations.

Of course, Toronto hospitals serve much larger populations than those of Huntsville and Bracebridge, including out-of-town residents with complex needs. Both also operate sophisticated research programs, whose work benefits hospitals across the country. In addition, in 2020, neither the hospital in Bracebridge nor Huntsville were actively engaged in a major capital campaign. Nonetheless, the data provides some sense of the volume of large donations flowing into Toronto’s urban core.

The discrepancy in donations could have consequences. If a community can’t come up with the money for its local share, the project will stall, preventing a community from securing much-need equipment for renovations, says Monika Turner, Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) policy director. She stresses that healthcare is a provincial responsibility — not a municipal one; and that it’s inappropriate for the province to be asking for municipalities to cover a share of the cost.

Natalie Mehra, executive director of Ontario Health Coalition, agrees: “Handing responsibility for infrastructure from higher levels of government that have more revenue flexibility to levels of government that have much less really is bad policy.”

Over the last decade, AMO has campaigned for the provincial government to change the policy, through letters, delegations and conversations with officials. But the work hasn’t led to a change. “[The policy] works well for the Province,” Turner says. “Not so much for the municipalities and communities.”

Hospital donations drop during recessions: study

Beyond the concerns about municipal budget strain, Dr. David Klein, has another concern about relying on philanthropy to fund capital healthcare projects: its volatility.

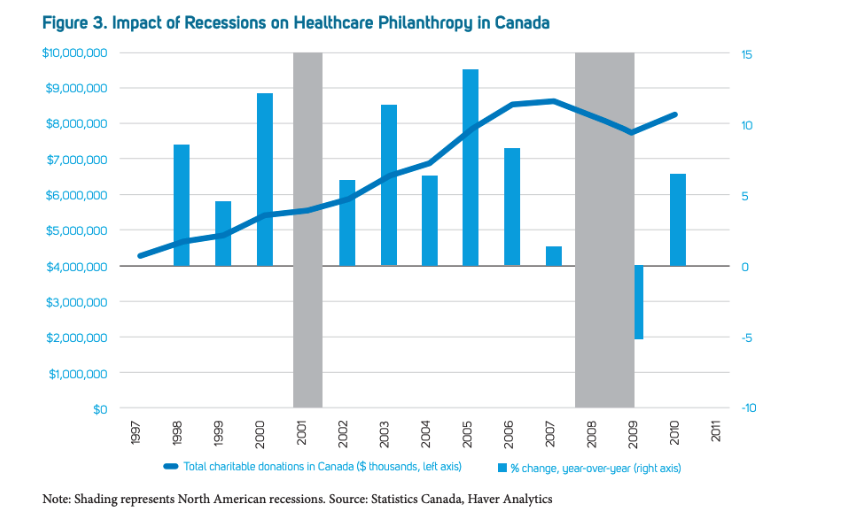

In 2013, Klein was part of a team of doctors and economists who analysed the relationship between stock market performance and total hospital donations in Canada, as part of a broader investigation into hospital capital funding. What they found was stark: when recessions happened in 2001 and 2008, hospital donations dropped. “When people’s pockets are well-lined and they’re doing well, that’s when they like to give back,” Klein says. “And when recessions come, not so much.”

The same correlation appears to be true when analyzing major gift donations. KCI’s research shows that in 2016, for instance, when the stock market dipped, the total value of gifts of more than $500,000 dropped to a five-year low. The total value of gifts dropped again in 2020, when the stock market dipped at the onset of the pandemic.

An inverse relationship between stock market performance and donations may be common sense, both when it comes to all donors and ultra-wealthy donors, but it could have big implications for hospital capital projects which rely on hitting their “local share” targets in order to move forward. “I think the danger, or the risk, is that the money isn’t there when you need it,” says Klein.

Can donors influence healthcare spending?

For some onlookers, there’s a third worrying trend when it comes to the rise of big hospital foundation donations: donor influence.

In their analysis of trends shaping the hospital foundation sector, KCI described that wealthy donors are increasingly interested in bringing both capital and ideas to the gift-making process.

“Today, transformational donors expect to bring more than money to the table,” the report notes, “and are increasingly emerging as integral thinking partners who want to contribute knowledge and expertise to the idea or problem at hand.”

Celeste Bannon Waterman, a partner with KCI, says donors don’t have “influence” but that some big donors are looking to have “involvement” at the early stages in a capital campaign. Before confirming the project with the government, Bannon Waterman says a hospital will sometimes conduct a “feasibility study,” reaching out to donors to get a feel for how much the campaign will be able to raise. This is done to ensure that the hospital is able to raise its local share once the government has made a commitment. It’s at that phase at the project where donors often want to have some input, she says.

Bannon Waterman says this could look like donors suggesting that they might give more if a particular aspect of a capital project was highlighted, like rethinking the role of the doctor in the emergency department, for instance, or ensuring there’s appropriate levels for mental health staffing.

She says she believes there are “appropriate balances and checks” on these conversations — that donors can’t dictate projects, no matter how much money they have, because the government has the final say with big capital budgets — but says that some donors are “increasingly wanting to bring those conversations to the table.”

Alicia Vandermeer, CEO with Scarborough Health Network Foundation says hospital donors have a variety of different approaches to determining what to fund. She says some donors, like the Northpine Foundation, are happy to fund whatever is most needed. She says Northpine Foundation’s Baskanderi specifically asked her what the hospital found hardest to fundraise for, and told her to put their gift toward that.

But once in a while, Vandermeer says, a donor will come to the foundation and say a family member has accessed care in a specific hospital department and ask whether the foundation has any donation needs in that area. “There’s a lot of need across the whole hospital,” Vandermeer says, “so we feel it’s our responsibility to take a look” at the long-term fundraising plan for that part of the hospital. “In some cases, there may be opportunities there that we’ll put out and maybe advance them, because the donor is interested, advance them now. And really have it be a win-win for the hospital.”

Under current funding framework, donations critical

Despite concerns raised about the role of big philanthropy in healthcare funding, nobody who spoke with Future of Good wanted these sizable gifts to stop. The way our system is structured, donations large and small provide money that’s essential to rebuild hospitals and finance necessary equipment.

The Northpine Foundation’s gift to Scarborough Health Network, for instance, will boost emergency department care, with the aim of creating the country’s first “no wait” emergency department, supercharge diagnostic imaging capacity, and finance a program intended to improve surgical outcomes.

Ward, Mehra and Klein, however, are all hopeful the government will take another look at the local share policy, considering the challenge it poses for communities of all sizes.

In addition, Ward is hopeful that other philanthropists will, as the Northpine Foundation has, take the opportunity to look for donation opportunities in northern and rural Ontario. In seeking to raise funds for the hospitals in Bracebridge and Huntsville, Ward is particularly hopeful that Ontarians who spend time in cottage country will see the value in ensuring the hospitals are well-served both during the summer months, when the population swells, and year-round for the region’s full-time residents.

“We want people to see it not just as a place to kind of drop in for the weekend and then leave,” he says. “There are people who live up here permanently who need these kinds of services on a permanent basis.”