‘Educational defiance’: In Gaza, makeshift classrooms keep hope alive amid war and hunger

Why It Matters

Resiliance in Palestine is showing up in unexpected ways, including in the classrooms that have sprung up in tents and ruins of Gaza. War can erase culture; therefore it's important to preserve literacy as much as possible.

By Mohamed Solaimane, Egab

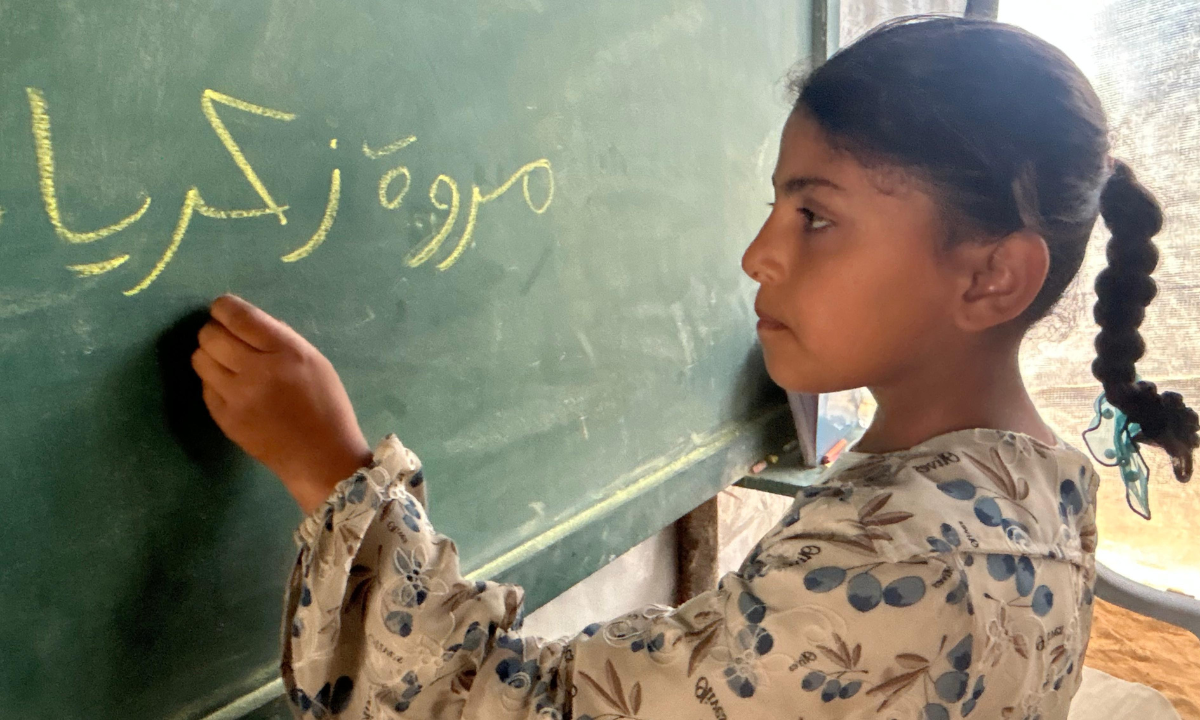

Every morning, 10-year-old Marwa al-Qudra stands at the front of her makeshift school in southern Gaza’s Al-Mawasi district, leading rows of students in a defiant chant: “Long live free Arab Palestine.” Her voice rises and falls, echoed by dozens of children standing in lines, their feet on dirt, their eyes fixed on her as she recites a poem about love for country and steadfastness.

Marwa is thin, her cheeks hollowed by hunger. Her body carries the signs of war and deprivation, and she speaks with a maturity beyond her years.

“I’ve only been eating one meal a day for weeks,” she said. “Sometimes, we don’t have bread. We eat whatever the community kitchen gives us.”

Still, she insists on attending school daily.

“I feel alive again when I line up with my classmates and write in my notebook.”

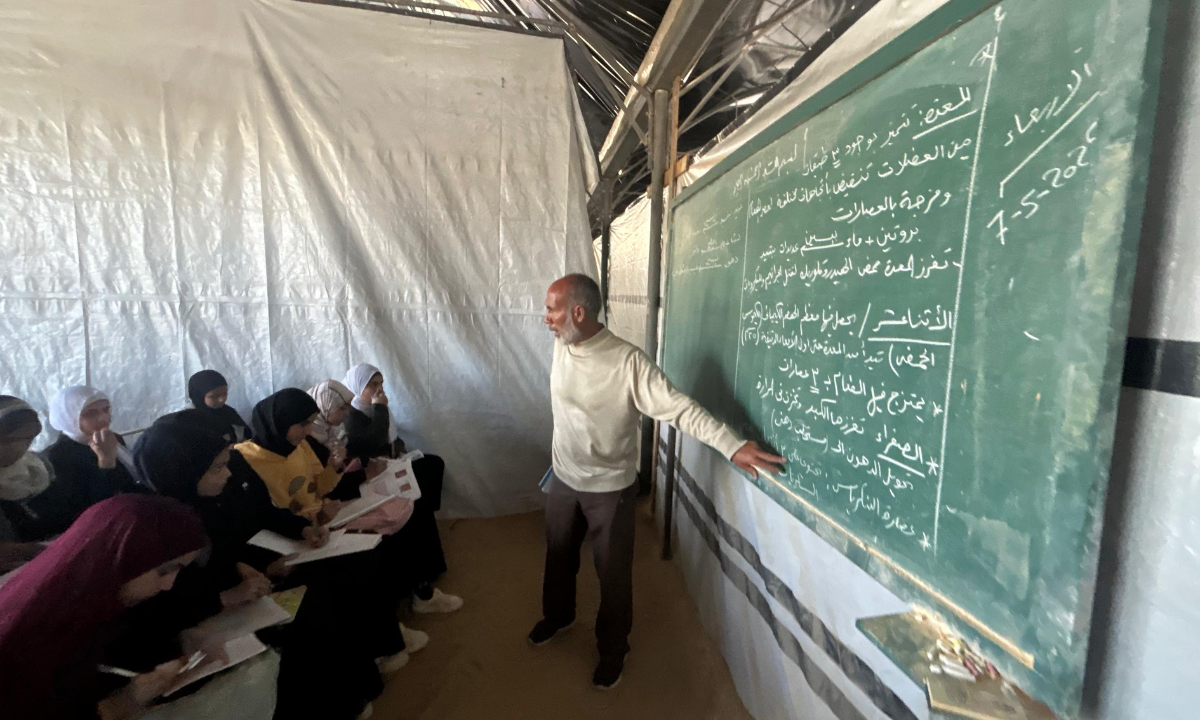

Her classroom is a makeshift structure: thick plastic sheets for walls, wooden crates that once carried humanitarian aid turned into chairs, and a salvaged blackboard propped up by rubble. Israel’s war on Gaza, which is entering its 20th month, has killed more than 55,000 people nearly a third of whom are children, and displaced roughly 2 million people, including hundreds of thousands of children.

An Israeli-imposed complete siege on the enclave has also starved the whole population as it hasn’t allowed food and other vital humanitarian aid in since March 2.

But for hundreds of children like Marwa, these makeshift schools, with sheets for walls and often without chairs or blackboards, are a sanctuary, a lifeline, and a declaration of resilience.

In the depths of Gaza’s ongoing war, hundreds of makeshift “field schools” have sprouted across the territory. Set up in tents, garages, and backyard shelters, they’re helping thousands of students study daily under bombardment and starvation – Marwa’s school, Al-Masar Field School, is attended by about 600 students.

Built by community volunteers and NGOs with minimal resources, these spaces serve as a fragile yet determined effort to preserve education during the war. By early 2025, nearly 90 per cent of Gaza’s schools had been damaged or destroyed, and most intact buildings had turned into shelters.

Marwa and her aunt now live in a tent after losing her mother, Asmaa (41), and brother Abdulaziz (22), in an Israeli airstrike in November 2023. Her father Zakaria (56) was later detained by Israeli forces while accompanying her injured siblings at Nasser Hospital during a raid in February 2024.

Despite these traumas, she finds solace in returning to the routine of school. “Even though death surrounds us, school reminds me I am still a student, that there is still life,” she said, clutching a donated notebook.

The Ministry of Education, backed by organizations like UNICEF, initially supported these efforts with hybrid in-person and remote learning programs. A temporary ceasefire in February 2025 allowed some classes to move back to partially cleared school sites.

But when Israeli strikes resumed in March, many schools were again shuttered. Some resumed activities in safer zones based on assessments by principals and parents.

“We consider education sacred”

For Dr. Mohammad Zarea, principal of the Al-Masar Field School in Al-Mawasi Khan Younis, the decision to resume schooling was both personal and political.

“I’ve worked in education for over 20 years,” he said. “But I’ve never witnessed such hunger for learning, even when families are starving.”

Zarea helped launch the school in November 2024 with just 60 displaced high school girls. Today, the school teaches 600 students from grades 1 through 12, and 100 more are on a waitlist. Thirty-five volunteers now work as teachers, assistants, and counsellors.

“Some parents skip meals to buy their children notebooks or shoes,” Zarea said. “Education here is sacred. It’s a national and religious duty.”

The school itself began in one room of a local volunteer’s home, then expanded into a semi-covered space built from agricultural greenhouse frames and plastic tarps. Wooden crates, often used for food aid, were repurposed into benches and desks.

“We’re constantly solving problems—space, materials, safety—but the biggest challenge is hunger,” he added. “Still, every day we reopen, it’s a win.”

Palestinians have long viewed education as a form of resistance. Gaza boasted one of the highest literacy rates in the Arab world despite being under a siege imposed by Israel and Egypt since 2007.

In 2023, the illiteracy rate among Gazans aged 15 and above was just 1.9 per cent, down from 13.7 per cent in 1997, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

According to Zarea, many students and parents view attending school as an act of defiance.

“The occupation can destroy our homes and kill our families, but they can’t erase our minds,” he said.

Instruction is centered around “learning kits” focused on math, Arabic, and English—skills identified as essential by the Palestinian Ministry of Education, drawing from lessons learned during COVID-19’s remote schooling. Despite the limitations, students receive basic education, and more importantly, a structure in a time of chaos.

“The day starts at 7 a.m.,” Marwa said. “It gives me purpose.”

Trauma, tents, and a hunger for learning

Wedad al-Astal, the school’s girls’ coordinator, said the contrast between the children’s lives in tents and their commitment to school is jarring.

“From a psychological and pedagogical perspective, this is impossible to explain,” she said. “But it makes sense in the Palestinian context—it’s a rejection of the occupation’s effort to de-educate us.”

She describes how students, some of whom are visibly malnourished and mentally exhausted, arrive before school starts and ask to stay after hours.

“It’s like they’re trying to say, ‘We have not been defeated. We are still learning.”

Al-Astal believes the experience can offer insights into trauma-informed education. “There’s a lot we can build on—from the resilience we’re witnessing to how we balance emotional and educational needs.”

What’s also striking, she said, is the political awareness of students.

“They know everything—about Palestine, the factions, Israel, even international responses. Their awareness is far beyond what children their age typically understand.”

Educational expert Dr. Mahmoud Assaf of Gaza’s universities sees the field schools as vital, though imperfect.

“They’re stopgaps,” he explains, “but they keep the educational spirit alive.”

While acknowledging the limits of learning under fire—“No classrooms, no desks, no exams”—he believes the greater success lies in preserving the psychological resilience of children through structure, play, music, and writing.

“In times of war, education is not about grades. It’s about protecting the soul.”

Yet, he cautions against over-romanticizing the model. Without systemic support, sustainability is fragile. “These initiatives must be institutionalized—tracked, funded, and supervised—or they’ll fade.”

He points to the halted final exams for the high school classes of 2006 and 2007 as a worrying sign, warning younger students may lose faith if they don’t see a pathway to graduation.

Still, Assaf sees one reason the schools have spread: what he calls “educational defiance.” “The message is clear: you bomb our universities, and we will teach in tents. You starve us, and we will learn by candlelight. That’s the Palestinian way.”

This piece was published in collaboration with Egab.