This independent journalism is made possible by the Future of Good editorial fellowship covering the social impact world’s rapidly changing funding models, supported by Future of Good, Community Foundations of Canada, and United Way Centraide Canada. See our editorial ethics and standards here.

It’s an exciting time for charity policy geeks.

Last year, the government issued a whack of promises in Federal Budget 2022 that have widespread implications for the sector.

Soon, foundations with assets of more than $1 million will need to kick out more money to the sector each year, all charities will need to provide more information on how their assets are invested, and charities across the country will have greater clarity on how they can grant to “non-qualified donees” — non-profits, grassroots groups, and others without charitable status.

Sharmila Khare is the head of the Canada Revenue Agency’s Charities Directorate — and the bureaucrat with the responsibility for implementing all of these federal promises. In late February, Future of Good spoke with Khare about these and other key files, gathering nine key insights from the conversation.

In Canada, all charities, including public and private foundations, are restricted by the CRA in how they can support the community by their “charitable purposes” — their stated goals and objectives which are outlined in their governing documents. Many have been hopeful that, with the passing of a new law in June 2022, more foundations will begin granting directly to non-qualified donees — organizations without charitable status. But for hundreds of foundations, their existing charitable purposes may pose a barrier.

For many foundations, one of their stated charitable purposes is “making donations to qualified donees” — rendering them, by definition, unable to make use of the government’s new law. Some have feared that in order to benefit from the new rules, each one of these hundreds of foundations will need to update their charitable purposes — a process that may involve legal fees and take board time away from other activities.

Khare signaled that these concerns may be well warranted. When asked about this issue, she said the CRA will be providing more information to the sector on how all charities can update their charitable purposes. She said each foundation’s compliance with their own charitable objects is specific, but added that “it is likely that some adjustments will need to be made.”

About five months after the federal government changed the law that makes it easier for foundations to work with non-qualified donees, the CRA published draft “guidance” on how all charities should interpret the law — and invited the charitable sector to provide their feedback on the document.

Sixty individuals and groups submitted their feedback, Khare said. Among other recommendations, respondents have encouraged the CRA to ditch the document’s heavy focus on “risk,” shorten the guidance considerably, and boost the rate at which a grant to a non-qualified donee is considered by the CRA to be “high risk.”

Khare says publishing the final guidelines is her team’s top priority among all of the policy products in development, and that she’s hopeful her team will be finished with the finalized version in the “coming months.” She acknowledged, however, that time is of the essence: “It’s in everybody’s best interest to see that final product in the public domain as soon as possible because the new rules are in effect right now.”

It can take a lot for foundations to change their behaviour. As a result, some sector professionals have said the CRA needs to take an active role in educating foundations about new ways of working with NQDs, encouraging this behaviour directly.

But those looking for the CRA to play such a role may be disappointed. “As the regulator of the sector, our responsibility is to put out administrative guidance so that the sector understands how we intend to administer the new legislative framework,” Khare said. “We’re not necessarily the marketers of the new policy.”

The Director General of the Charities Directorate said sector organizations are better positioned to market this new approach. This suggests that philanthropic networks, like Philanthropic Foundations Canada, Community Foundations of Canada, and Environmental Funders Network, and charity and non-profit associations like Imagine Canada, Ontario Nonprofit Network, Alberta Nonprofit network, and others, may need to play a bigger role in sharing information about the new law.

In last year’s Federal Budget, the government committed to improve the CRA’s collection of information from charities on their use of Donor Advised Funds.

DAFs are charitable accounts held commonly with foundations, which operate like a private foundation, but require much less effort on the part of the benefactor. As a result of this convenience and other factors, DAFs have exploded in popularity in Canada in recent years. Researcher Keith Sjögren has found that in Canada, DAF assets have increased by about 20 per cent over the past five years; and are predicted to reach $10 billion by 2026.

Proponents say this growth in the DAF market is great news for charities, who can benefit from new donations. But DAF detractors caution that these giving vehicles are not subject to many of the regulations required of private or public foundations, despite, in some cases, being just as large. For instance, individual DAFs are not subject to the disbursement quota — the base rate that a charity must spend on charitable activities or grant to other groups each year.

Khare wouldn’t say what kind of information the CRA will require of foundations or charities that operate DAFs, but said we’ll know more in the coming year. The CRA expects to roll out a new T3010 form in fall 2023, Khare said. The T3010 is a form charities have to complete annually, which asks information about their assets, fundraising and donations. The updated form will include new questions about DAFs and will also ask new questions about charities’ investments, another promise made in Federal Budget 2022.

“I don’t think we know enough as a government on the use of DAFs in the charitable sector,” Khare said. “So the first step will be for us to collect more information through the T3010, which will inform tax policy development in the future.”

For many years, some charity sector professionals have called for more data on the diversity of charitable sector boards. Heeding these calls, in June 2019, the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector recommended the CRA amend the T3010 and the T1044 (the form for federally incorporated non-profits) to ask charities about board diversity.

Three years later, and the T3010 and T1044 are mum on this subject.

Khare said progress on this file is not within her area of responsibility, per se. She noted, however, that there’s been some work on this issue underway in the Senate — a motion in May 2022, by Senator Ratna Omidvar called on the government to implement the Special Senate Committee’s recommendation. Khare also implied that collection of this data would require a change to the Income Tax Act, which has not yet occurred.

Khare says the T3010 serves two functions: public transparency — providing Canadians with information on the charitable sector; and compliance — collecting the information the CRA needs to ensure charities are in compliance with the Income Tax Act.

“Currently, there are no provisions in the Income Tax Act that relate to collecting information about the diversity of the directors in charities or non-profit organizations,” she said. “The CRA would need a reason to collect that information. From a compliance perspective, that is not information that I need to run my program today.”

In recent years, a pair of studies have raised concerns about potential anti-Muslim bias in CRA’s treatment of Muslim-led charities.

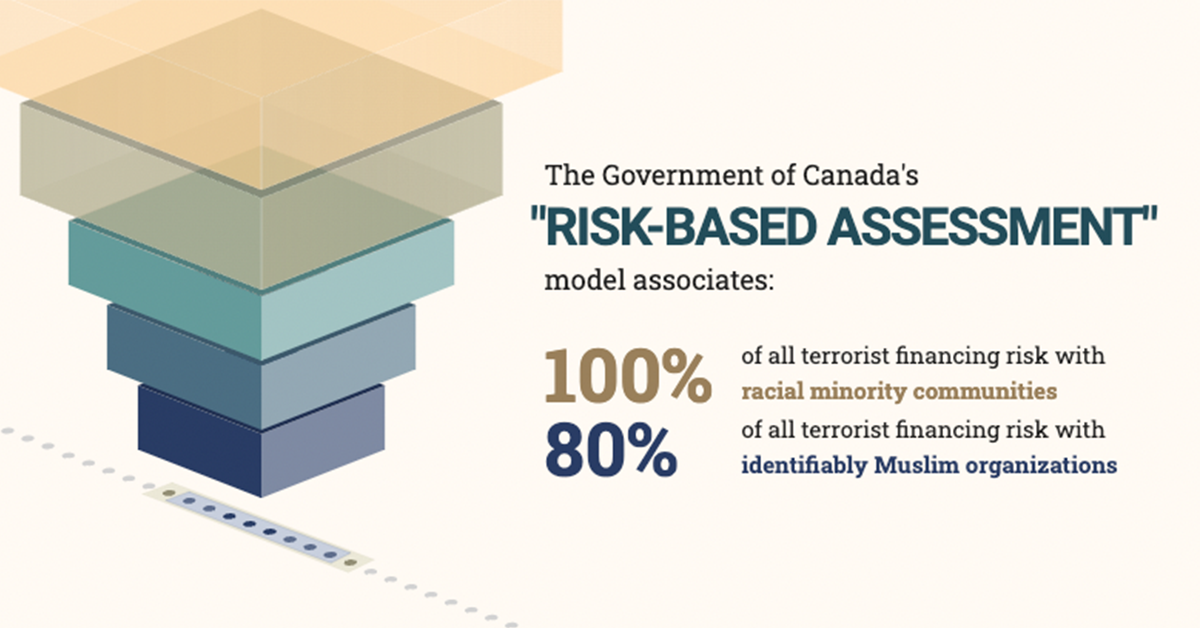

In 2021, the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group found that of the sixteen charities audited by the CRA’s counterterrorism financing group, the Review and Analysis Division, between 2008 and 2015, eight had their status revoked — six of which were Muslim-led.

Later that same year, a report from University of Toronto and National Council of Canadian Muslims raised concerns about “structural bias” embedded in federal anti-terrorism financing and anti-radicalization policies, which, they, too, suggested make Muslim-led charities “exceptionally vulnerable to audits, or worse, revocation of charitable status.”

But Khare said it’s not so: “There have been allegations of bias, but I think the policies and procedures and systems that we have in place in the Charities Directorate are designed to prevent bias presenting itself in the selection of a charity for audit or the denial of a registration.”

She noted that charities are “particularly vulnerable” to abuse by terrorist financing and said the CRA’s Review and Analysis Division is a “niche area” that was established to protect the sector from this kind of abuse. The division, she said, reviews all applications for charitable status to ensure there are no risks of terrorist financing, monitors the sector to identify new trends and potential risks, and conducts audits when risks have been identified.

Khare added that there are a number of “checks and balances” in CRA’s systems to prevent bias, including that staff work in a team-based environment (so it’s never one staff member making decisions about audits alone) and that staff get training on unconscious bias.

Still, Khare said she welcomed a forthcoming report by the Taxpayer’s Ombudsperson, which was requested by the Minister of National Revenue in 2021, into the bias concerns raised by Muslim-led charities. “We’re looking forward to those recommendations and seeing how that will shape our work going forward,” Khare said.

In 2019, the federal government established the Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector, a permanent body composed of top charity lawyers, executives, accountants, and others, whose mandate is to provide the Minister of National Revenue and the CRA with input on sector issues. That group has gotten some attention in the broader sector, including concerns by some that its membership has lacked racial and experiential diversity.

But, there’s another, perhaps, less well-known, advisory body that the CRA turns to for input, too: the Technical Issues Working Group.

Established in 2004, the group meets twice per year, serves two-year terms and is composed many of the same sorts of professionals as the ACCS — lawyers, accountants, and representatives from umbrella groups, like Imagine Canada, the Association of Fundraising Professionals, and the Canadian Centre for Christian Charities. Like the ACCS, the TIWG (referred to as the “TWIG” — despite it being not quite phonetically correct) also provides the CRA with advice on charitable sector issues.

“They’re generally our go-to group when we are consulting on a new policy document when we are thinking about an operational change within the Charities Directorate,” says Khare, who notes, for instance, that CRA consulted with this group on the draft NQD guidance and when the agency introduced new online services for the sector.

Khare says if there’s one thing she wished the sector better understood about her team, it’s that they’re not as scary as you might think: “We are here to help,” she says.

Khare says her team welcomes your calls — even anonymously — if you have questions, concerns, need guidance, or need help navigating the CRA’s website.

She acknowledges that CRA’s role is fundamentally focused on regulation and enforcement, but says, in her heart, that her team’s desire is to see a strong and vibrant charitable sector — “a sector that Canadians can trust.”

“The charities directorate — it’s kind of like we’re our own little world within the tax agency,” Khare says. “People in this directorate are here because they’re very passionate about this particular sector. They’re here in the Directorate working by choice.”

Despite Khare being a relative newcomer to her role, having been promoted to Director General in May 2022, she’s no newcomer to tax policy nor the charitable sector.

The senior bureaucrat trained as an economist, and has held roles with the federal Department of Finance, the World Bank, and now CRA; but her roots in the sector began with her family.

“My mom was a big inspiration,” Khare says. “She came to Canada as an immigrant. She was a trained architect, but couldn’t practice in Canada…So, her life really became about being that great grassroots volunteer, and she impacted so many people. Many of the things she worked on, for immigrant women and seniors in the community where I grew up, still exist today.”

Khare has followed this example in her own life. As a young person, she was involved with Girl Guides and the Duke of Edinburgh program, and hasn’t looked back. “I can’t remember a time of my life, since I was a young person, where I wasn’t engaged in some type of regular volunteer work,” she says. “So, it’s a sector that I really care about.”

A full transcript of this conversation, with additional questions and answers, is available here.