Putting charities in charge: New $9-million Black-led fund - one of largest-ever in Canada - to centre applicants in grant decision-making

Why It Matters

Black leaders are hopeful that a participatory grantmaking process, being used by the Foundation for Black Communities, will model how governments and foundations will engage with and fund Black community organizations in the future.

When organizations apply to a new, national, $8.9-million fund for Black communities, it won’t be a group of far-away donors or government staffers reviewing their proposals — it will be local peers.

On Monday, the Foundation for Black Communities (FFBC), a national community foundation, launched a new granting program to support Black-led, Black-serving and Black-focused (B3) organizations nationwide.

The program is the first major distribution of capital from the $200-million Black-ed Philanthropic Endowment Fund, a federal program which the FFBC was selected to administer.

The Black Ideas Grant is not the first Canadian fund to support B3 organizations — in 2019, for instance, the federal government invested $200 million in the Supporting Black Canadian Communities Initiative — but it’s the first to be governed by a Black-led and focused community foundation, said amanuel melles, executive director of the Network for the Advancement of Black Communities.

“Now they have a locus of control. They have control [over] how they can design, implement and create this fund…This means they have latitude to try new things,” he said.

The design of the Black Ideas Grant suggests FFBC is wasting no time doing just that, melles added.

In determining organizations to be selected for a grant, the foundation will rely on local committees comprised of representatives from applicant organizations and other local experts.

The scores provided by committee members — more than 100 volunteers from coast to coast — will inform the granting decisions made by the foundation’s board.

Though peer reviews aren’t unprecedented, this approach has likely not been used on this scale before in Canada, said Juniper Glass, a philanthropy consultant who has supported foundations to engage in participatory grantmaking.

“They’re trying to shift the power,” she said. “I think it’s actually a really courageous thing to do.”

But while the capacity required to implement national peer reviews is significant, FFBC staff say it doesn’t require bravery.

“Black communities have been collectively deciding for centuries,” said Michelle Musindo, a FFBC program manager.

“So, it’s not scary, it’s critical…It should be the standard. We should all think about [using] participatory grantmaking all the time.”

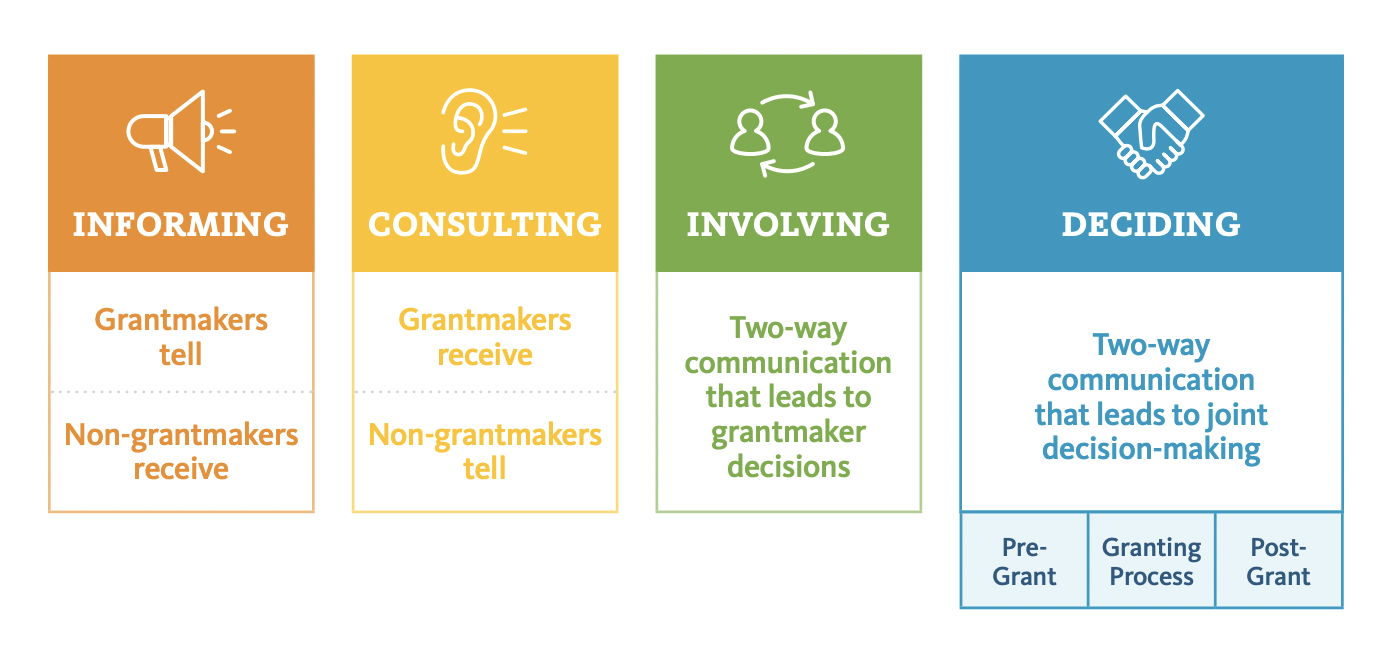

The participatory grantmaking spectrum

Traditionally, funders decide where, when, to whom and how funds should be distributed based on their vision for social progress.

Within private foundations without staff, family members or close family friends on a foundation’s board of directors commonly determine granting strategy and recipients.

With government programs, ministry staff typically design funding programs and assess applications, making recommendations approved by a minister.

These approaches can be expedient but have their drawbacks.

Funders sometimes create overly complex application processes, wasting applicants’ precious resources to compete for funds. Funders also sometimes lack the lived experience or local expertise to make granting decisions in the best interest of a community’s vision for change.

Grantees have increasingly called for more power in decision-making based on these and other frustrations.

Funders have responded, developing a spectrum of approaches that offer progressively more control over decision-making for prospective beneficiary organizations.

At the far end of this continuum are so-called closed collectives, where funders empower community organizations to decide amongst themselves how a pot of money should be distributed.

These decisions are typically made through meetings where organizational representatives discuss their funding needs and how those stack up relative to their peers.

Several Canadian community foundations have used this approach, but the fund sizes have typically been more modest.

For their 2023 Community Vital Grants, for instance, the Community Foundation of Greater Peterborough used a closed collective process to distribute about $100,000.

This is a process FFBC would like to use in future granting, but it wasn’t feasible for this first fund due to time constraints, said Musindo.

Instead, the foundation’s approach will use participatory committees, the most common practice in participatory grantmaking, according to PGM consultant Kelley Buhles.

FFBC’s peer review process

Once applications are submitted from B3 organizations nationwide, FFBC staff will form local review committees in communities nationwide.

Half of the members of each group will be representatives from applicant organizations, and the other half will be local community experts, making this a community committee.

This differs from a representative committee, where local experts mix with traditional decision-makers, such as board members or donors, or a rolling applicant committee, where former grant recipients make funding decisions about a subsequent funding round.

To help assess applications, review committee members will receive a rubric and training on the program’s objectives from FFBC staff and will have three weeks to evaluate the proposals.

To compensate for time spent, committee members will be provided with an honorarium for their time at about the rate of the local living wage, up to a maximum, Musindo said.

While the process has more moving parts than a traditional review process, foundation staff and Black community leaders said it’s well worth it.

Why PGM? A return to roots

The decision to use participatory grantmaking is crucial because it’s a return to a style of collective decision-making common to some Black communities, said Liza Arnason, founder and chair of the Ase Community Foundation for Black Canadians with Disabilities.

“When you do it this way, you give light, acknowledgement and support to how we’ve always done things in the past,” she said.

For centuries, community members in many African and Caribbean countries have participated in collective fund distribution processes, such as sou-sous. Within these circles, participants contribute an equal amount regularly, rotating who receives the full pot each session based on need or distribution schedule.

“This is how we moved through slavery. This is how Africans survived colonialism,” Arnason said.

“What this fund is saying is that we’re going to do it the way we’ve done it for hundreds of years, that have worked for centuries — because this other way hasn’t been working for us.”

Proponents of participatory grantmaking also say the approach fosters more robust ties between organizations in local communities.

Last winter, Arnason participated as an applicant and peer-reviewer on a smaller fund distributed by FFBC.

The process allowed her to learn about the work of peer organizations with whom she could partner in the future, she said.

Participatory grantmaking can also support improved community cohesion by bringing greater transparency and accountability to funding decisions, said melles.

Typical grantmaking processes often leave applicants in the dark about how decisions are made, which can sometimes lead to community acrimony.

By contrast, he said participatory grantmaking can bring a level of clarity applicants welcome by engaging stakeholders in the process.

The approach can also help to capture the wisdom of diverse communities, melles added.

“Black is not homogenous. Black is a very diverse family from Afro-Nova Scotians to newcomers to continental Africans to Black Canadians and the Black diaspora.”

Using a participatory process allows FFBC to cement a “relationship of meaning” with diverse Black communities across the country, said melles.

The downsides? Risk of loss of IP

Despite the upsides, participatory grantmaking doesn’t come without its challenges.

For one, it takes a lot of work on the part of the foundation to set up a participatory process and support community members to make decisions, said Glass.

Some Canadian grantmakers who have piloted PGM have paused using this approach because it required so much energy, she added.

Some other foundations have shied away from the approach because of a concern about conflicts of interest — that applicants can’t be objective about their peers’ applications or could steal intellectual property, said Mary Abdo, a consultant who has researched participatory grantmaking.

But though these concerns are understandable, Arnason said the benefits of the participatory approach outweigh the risks.

In particular, it’d be challenging for an organization to truly copy another’s idea because they would lack the partnerships, expertise and history to make it happen, she added.

Hoping for a ripple effect

melles is hopeful the Black Ideas Grant is more than just a funding program — he hopes it can serve as a catalyst and offer a template for how other funders can support Black communities.

“The biggest investment, in terms of change in communities, comes from government — federal, provincial and local government. That’s where we hope funding reform will happen,” he said.

“I hope this is not just a grant program. It’s an opportunity to bring innovation and creativity so that we can not only support Black communities but influence governments in terms of their funding practices.”