Where does the Social Finance Fund stand in a post-COVID universe?

Why It Matters

The government’s landmark Social Finance Fund was set to launch this year, claimed to generate up to $2 billion in economic activity and create 100,000 jobs. But where do those plans stand in the midst of 2020’s extreme events, and what role could it play in rebuilding communities after COVID-19? In the first article in a new special report, Future of Good examines what the fund means for Canada’s social finance market, and for societal recovery.

When the landmark $755-million Social Finance Fund was first announced in 2018, the government could never have expected the circumstances they would face in 2020 – the year the fund was expected to launch.

The COVID-19 pandemic has left millions of Canadians in desperate need of support. The economic impact has been devastating, particularly for low-income Canadians. Businesses are struggling to stay afloat and unemployment has been soaring. More than eight million people have applied to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit so far.

For Canada’s most vulnerable people, COVID-19’s impact has been particularly severe. The disease has disproportionately affected the elderly, with 80 percent of deaths in care homes. It is having a profound social impact, too. Reports suggest domestic violence has increased by 20 to 30 percent in some regions, the government has said.

The pandemic has also made it difficult for the social impact sector to respond. Not only facing a surge in demand and fewer volunteers to hand, organizations have far less cash to help out – COVID-19 is expected to cost charities and non-profits between $9 billion and $15 billion, not including the damage to social enterprises.

These bleak circumstances have made the launch of the Social Finance Fund more important than ever. As communities across Canada look for ways to rebuild, thinkers and leaders in the social impact sector believe the social finance market could prove a vital tool for recovery.

For this exclusive new special report on the Social Finance Fund, Future of Good has been speaking to the people and organizations at the heart of building the social finance market in Canada, taking an in-depth look to find out what this all means for the social impact sector to build back better.

In part one, we examine the state of play. What does the Social Finance Fund aim to do, how are communities preparing for it, and what impacts has the extreme disruption of COVID-19 had on the government and its partners’ plans?

What is the Social Finance Fund?

Social finance is the mobilization of private capital to address social and environmental issues. Often referred to as “impact investing,” it usually involves investors – from financial institutions and institutional investors to charitable foundations and governments – lending to organizations working to achieve positive social or environmental impact, in exchange for a financial return.

These social purpose organizations can range from charities and non-profits through to social enterprises and even traditional for-profit companies whose activities have a positive social impact – such as affordable housing or green energy firms.

Announced in the fall economic statement in 2018, the Social Finance Fund is an attempt from the federal government to catalyze the growth of a social finance market in Canada, which experts hope could boost community recovery.

“I think it could have a monumental impact,” said Jeff Cyr of Raven Indigenous Capital Partners. “Social purpose enterprises – it’s in their name – operate at the intersection of profit and purpose. They drive local economies and address critical social and environmental challenges.”

Eventually, Ottawa hopes to create a self-sustaining social finance ecosystem whereby private and philanthropic capital can be employed for social purposes in communities across the country. With the fund, he said, the government is “leveraging public capital to increase the inflow of private capital and supporting the development of the whole social finance ecosystem.”

For every dollar of public capital invested, whoever manages the Social Finance Fund will be required to leverage a minimum of two dollars of non-governmental capital. Ottawa claims that the new fund could generate up to $2 billion in economic activity, and help to create as many as 100,000 jobs.

The government’s investments will be “concessionary,” Cyr explained, meaning Ottawa is expected to accept below market returns and extended time horizons. This both enhances the attractiveness of the social finance market to private investors and expands the types of capital available to social enterprises, he said.

A social finance market already exists in Canada and globally, to the tune of $14 billion and USD$502 billion ($675 billion) respectively according to estimates. But governments around the world, such as the United Kingdom and South Korea, have been putting forward capital to accelerate growth of the social finance ecosystem in their countries.

In Canada, different forms of social finance have existed for decades, but recent years have seen momentum grow more quickly – with several different types of social finance actors emerging.

One type is “place-based” investors, which support social impact organizations locally, such as VERGE Capital in London, Ontario. Other impact investors might focus on supporting particular issues, sectors or populations, like Windmill Microlending which helps internationally-trained immigrants and refugees.

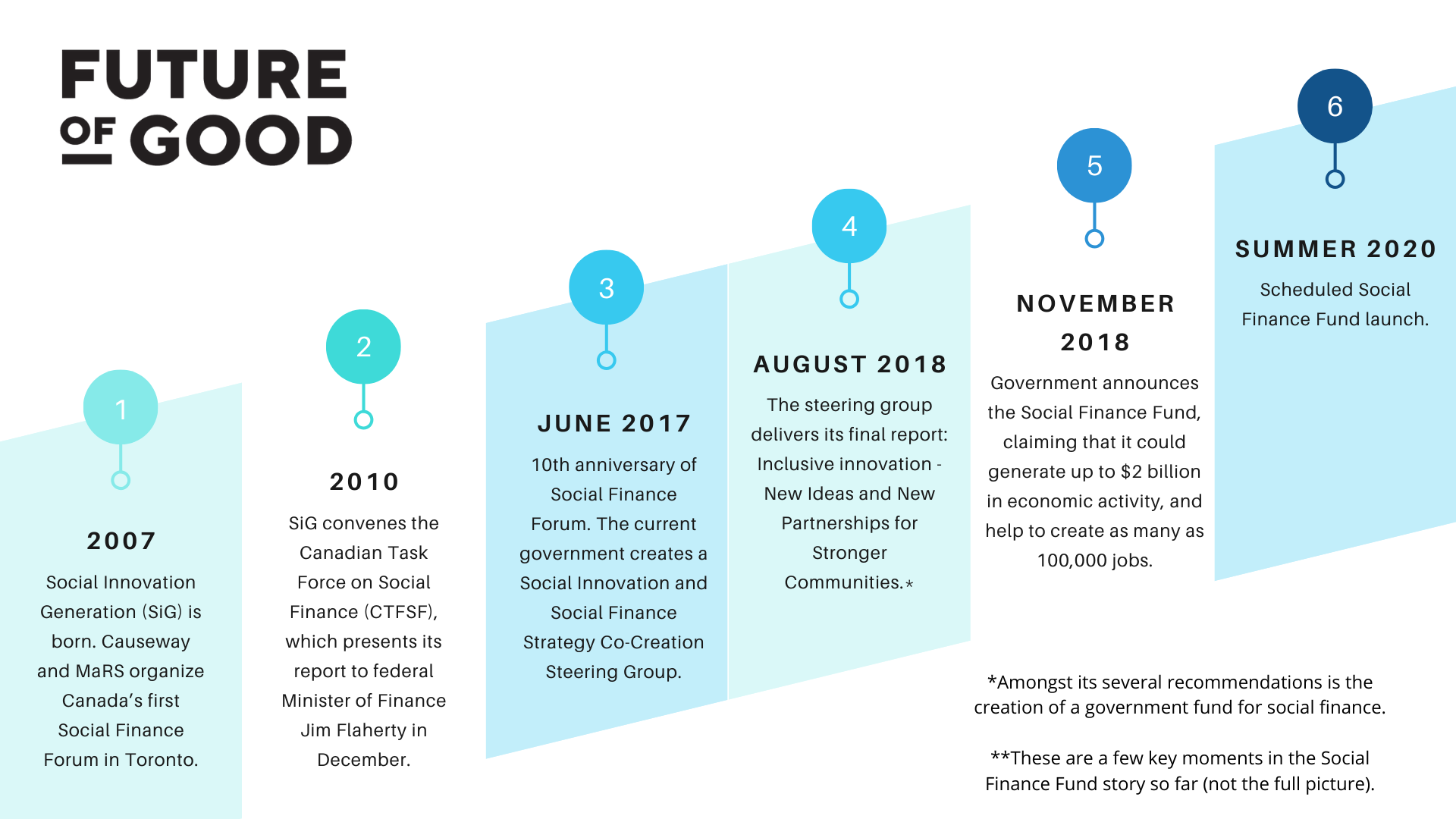

This growth of social finance has led to a greater push for governments and more major institutions to get involved. In 2007, the first Social Finance Forum was held by MaRS in Toronto, in 2010 a Canadian Task Force on Social Finance was set up, and more recently in June 2017, the current government created a Social Innovation and Social Finance Strategy Co-Creation Steering Group. The government has also been preparing to name a new federal Social Innovation Advisory Council, with 12 to 15 external experts to support the implementation of its social finance strategy.

The steering group delivered its final report in August 2018: Inclusive innovation: New Ideas and New Partnerships for Stronger Communities. Amongst its several recommendations was the creation of a government fund for social finance, which the government announced a few months later.

“Our response was to suggest the federal government supports the organic, interconnected ecosystems that are already making communities more sustainable and inclusive,” said Ajmal Sataar, CEO of Small Economy Works and co-chair of the steering group.

“We believed the creation of the Social Finance Fund, in particular, would accelerate the development of the social finance market to its full potential, and also be a catalyst to grow the report’s other integrated ecosystem-wide recommendations,” he said.

How will it work?

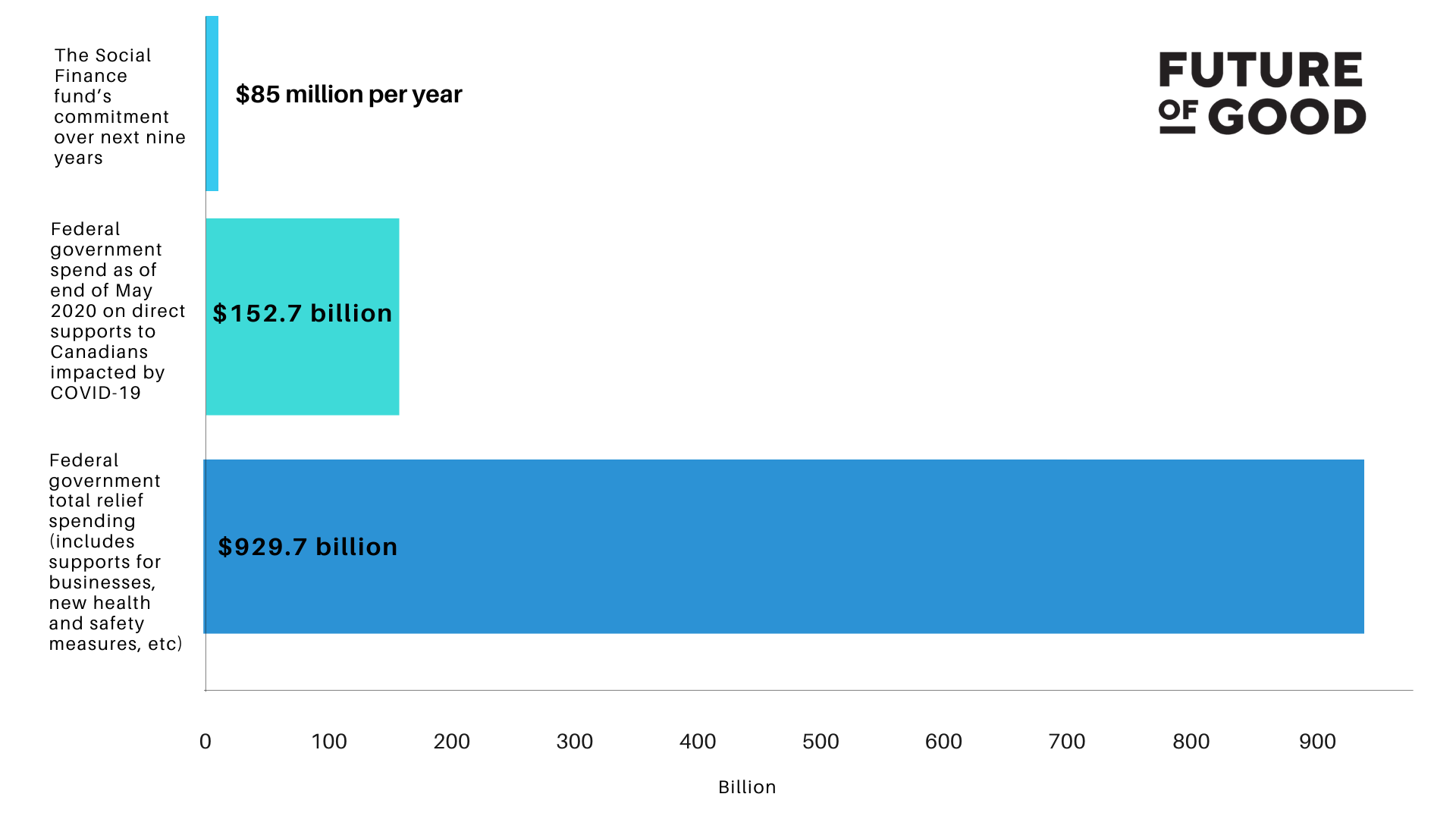

The fund is expected to allocate approximately $85 million per year of government funds to social impact organizations over 9 years, beginning in fiscal year 2020-21. The federal government has used a very broad definition of “social impact organizations” to be invested in, including “registered charities, non-profit organizations, co-operatives and businesses that consider the social effects of their activities.”

Although the government has been relatively thin on details so far on how the money will be spent, its social finance strategy has involved an explicit aim to support communities facing “persistent and complex social problems,” including Indigenous people, seniors, youth, immigrants, and women fleeing violence.

“The government is aware of the potential of social finance to promote growth that works for everyone, create jobs for vulnerable Canadians, and help solve urgent challenges such as food insecurity or climate change,” said Jessica Eritou, from the office of Ahmed Hussen, Minister of Families, Children and Social Development, in an email to Future of Good.

In the 2019 budget, the government pledged to allocate a minimum of $100 million over that period towards projects that support greater gender equality. And in the first year, $50 million will be put towards a separate new Indigenous Growth Fund. Jointly supported by the Business Development Bank of Canada and other public institutions, that fund will make capital available to Aboriginal Financial Institutions to provide loans to new and expanding Indigenous businesses.

Alongside the Social Finance Fund, the government created the Investment Readiness Program (IRP), which has been running for the first of its two years. With $50 million in funding, the aim of the IRP is to build capacity across Canadian communities, so that social finance funds have things to invest in – especially in vulnerable areas which often need the most capital, yet may be least prepared for investment.

Developing a social finance market is “not really about the supply of capital that’s available, it’s more about the demand for social finance,” explained Adam Jog, a research associate at Imagine Canada. “The Investment Readiness Program itself is an example of a major lesson learned from the UK experience of social finance,” he said, where a lack of capacity among social purpose organizations meant there were insufficient investment options.

In order to build that capacity, the government has 24 implementation partners who fall into three broad categories: readiness support partners, expert service providers and ecosystem builders.

There are five “readiness support partners” whose job is to manage the program and distribute IRP funds to social purpose organizations. In order to receive investment, organizations have to be incorporated, as well as satisfying various other criteria, including a demonstrated need for their mission in the community, an innovative business model, and suitable financial structuring.

Community Foundations of Canada has been the main coordinating partner, managing $22 million of the funds across Canada, while Chantier de l’économie sociale is giving $8 million to Québécois organizations, the Canadian Women’s Foundation focusing $3 million on gender issues, and the National Association of Friendship Centres providing $1.12 million across its network.

The Canadian Women’s Foundation was the first to launch, helping to support 12 organizations in its first round of funding, including YWCA Halifax in Nova Scotia, Women’s Shelters Canada and the Women in Need Society of Calgary.

The National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association, meanwhile, another readiness support partner, is using $3.1 million of the IRP to prepare its network of over 50 Aboriginal Financial Institutions for the Indigenous Growth Fund, which it runs.

The money will be used to boost the institutions’ local capacity to identify and support Indigenous entrepreneurs, said Shannin Metatawabin, the association’s CEO. “This will allow them to dig into the community even more,” he said, “by building programs to make sure that entrepreneurship is an option that everybody is considering.”

“Investment ready”

The organizations which are selected by the IRP can then spend the money on expert service providers – the second group of five partner organizations which the government is funding – to advise them on how to become investment ready. This support generally comes in the form of expert advice and consultancy.

Each service provider looks after different types of organizations or aspects of work. SVX, for example, focuses on the technical aspects of raising capital, such as financial modelling and structuring investment offerings, said its CEO Adam Spence. Raven Indigenous Capital Partners, meanwhile, is focused specifically on organizations which help Indigenous people and women.

“Investment readiness means if they were charitable or not-for-profit that they need to pivot their mindset slightly into: how do I generate revenue?” Cyr explained. “Many not-for-profits and charitable organizations are perfectly situated to take some of the things they do, look at the value proposition, value it, and turn it into a working business model.”

Importantly, though, social finance isn’t for every social impact organization. For some organizations, he pointed out, their work might not suit pivoting towards creating revenue from their activities, and they should remain traditional charitable service providers.

By the end of May, over 50 social purpose organizations had received funding through the IRP to improve their ability to participate in the social finance market, the federal government told Future of Good. Over the course of the pilot project, which is due to end next March, it expects at least 250 more will be funded.

In order to build the ecosystem around social impact organizations, the government has funded a third group of partners called “ecosystem builders.” They are tasked with addressing “system-level gaps” in the social finance ecosystem such as social research and development (social R&D), impact measurement, and building capacity in social finance intermediaries.

Imagine Canada, for example, is working to improve the awareness about social finance among charities, Jog said, and helping other actors like investors work more effectively with charities.

Another ecosystem builder is the Canadian Community Economic Development (CED) Network, which has broad reach in local communities across the country.

If social finance is to reach communities which most need it, it needs to be very place-based and local, said Sarah Leeson-Klym, the organization’s regional networks director. “We’re not going to have a very rigorous or a very robust system if it’s all administered centrally,” she said. “It’s like an ecosystem that has to exist across the country if this whole social finance world is going to increase.”

A post-COVID-19 universe

The plans of the federal government and its partners, however, have been impacted profoundly by the COVID-19 pandemic and global recession. Questions are being raised about the new role which the Social Finance Fund could play in community recovery, and whether its rollout should be accelerated.

Still in crisis mode, Ottawa is yet to reveal its position. The government is “currently re-examining the timelines for the fund’s launch,” said Jessica Eritou from Minister Hussen’s office, and has received proposals from a variety of stakeholders to accelerate its launch, which “officials are examining.”

“The government welcomes additional input and ideas on the Social Finance Fund’s potential role in supporting a successful, sustainable and inclusive post-crisis economic and social recovery,” she said.

While the sector awaits those answers, COVID-19 has been having a direct impact on the organizations implementing the IRP program.

“As our reviewers were completing their process [of approving applications], the whole world moved sideways,” said Sara Lyons, who is leading Community Foundations of Canada’s (CFC) implementation of the IRP. CFC had already decided but not finalized or announced its first round of IRP investees.

Lyons explained that CFC has been building in time for thoughtful dialogue with the successful social purpose organizations about the viability of their plans in the face of COVID-19. “People applied in universe A and they will be getting the money in universe B,” Lyons said. “We can’t give people money for something that no longer makes any sense.”

Although it is still unclear what exactly the social finance fund will be investing in, and when the funds will be disbursed, said Lyons, it is still an “inherent good” to “create an ecosystem” in preparation.

Undoubtedly, many of their individual plans and priorities may have changed substantially. Over the coming weeks and months, communities will learn what it will take to recover, and social purpose organizations are likely to be at the heart of those efforts.

The urgency of the COVID-19 situation may help to push the Social Finance Fund forward, said Leeson-Klym. Although the federal government is yet to meet the sector’s demands for a stabilization fund, as set out by Imagine Canada, “there’s really fast policy development,” she said, “and we’re seeing programs change really quickly.”

“And on the sector side, maybe because the IRP had already been in place, there’s a lot of people talking that weren’t,” said Leeson-Klym, “and a lot more willingness to try to align ideas.”

“That’s a unique moment, and I think the next few months will be really busy and really exciting,” she said, “to see whether we can really be catalytic in how things change.”