“Shelters are becoming de facto long-term housing” as Ontario grapples with alarming rates of homelessness

Why It Matters

Ontario is the only province where housing responsibility has been passed down from the provincial government to municipalities. Many shelters rely on a patchwork of funding sources, and are having to consider more financially sustainable options.

When people seek support at Street Help in Windsor, Ont., Anthony Nelson is often one of the first people they talk to.

And increasingly, Nelson is seeing whole families come in for the organization’s meal services, which run three times a day.

“Our food is going really fast here,” he said.

With the help of volunteers and donors, Nelson and his team also distribute essential winter products, such as hats, coats, gloves and sleeping bags.

Like other cities across the province, Windsor has seen a sharp increase in the number of unhoused people sleeping rough. Nelson said the city’s response is often to move encampments from place to place, a process that drives people further away from the resources they need, like the services provided by Street Help.

“If some say they want to go to Street Help to get a meal, they have to walk, because most of them don’t have transportation,” he said.

Nelson’s frontline experience reflects a larger trend, one that’s alarming advocates across Ontario. A report published by Helpseeker Technologies and the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) this January estimates there are more than 81,000 people currently experiencing homelessness in the province, an increase of 25 per cent from 2022.

And that number only reflects people known to shelter services in Ontario.

The report’s authors believe that the number of people experiencing homelessness is likely far higher, noting available data doesn’t include those staying with friends and family, or in other temporary accommodations.

“Even though they’re reporting such a large number, it’s probably more,” said Laura Dumas, executive director of Start Me Up Niagara, a resource centre providing support services for people living in poverty, with addictions and with significant mental health challenges.

“The Point-in-Time (PiT) count is completely voluntary, so if someone wants to stay under the radar, they won’t participate.”

The number of people known as homeless in northern Ontario—where temperatures are significantly colder in the winter months—tripled between 2016 and 2024, according to the association.

The AMO’s data also highlighted that Indigenous people represent nearly half of all those experiencing chronic homelessness in northern Ontario. Children and young people make up a quarter of the chronically homeless in the whole province, while refugees and asylum seekers are also a large part of the unhoused population.

Previous research has identified a “revolving door” between homelessness and those in Ontario’s criminal justice system. Many of those leaving incarceration are faced with long wait times to secure housing and other supportive services. Cost was another barrier cited.

However, homeless shelters and support services are increasingly seeing people come through their doors who just can’t keep up with the rising cost of living in the province.

Windsor’s Welcome Centre supports women experiencing homelessness and coming out of abusive relationships and is seeing the impact of the housing crisis first-hand.

“We’re seeing more and more women coming in and presenting with the same thing: they got an eviction notice, or had a breakup, and thought they would find a place but didn’t,” said executive director Lady Laforet.

“This is not a [housing] market like anything we have seen before, and when you’re looking at vacancy rates of one per cent, people get an eviction notice and think: ‘Okay I’m going to go look for a new place’ and then actually get out there and see they’re so priced out of the market.

“We’re seeing a lot more women coming and going: ‘I’m shocked that I’m here. I didn’t think that I would end up here.’”

Lack of transitional housing cited

East of Windsor, in Brantford, Rosewood House has also seen an increase in people coming to the organization because of a single trigger event, like losing their job or separating from a partner, said executive director Tim Philp.

But the majority of cases are significantly more complex, involving mental health and addiction, he observed.

“One person described it to me as living your life walking through molasses,” Philp said.

Back in Windsor, Laforet has not only seen an increase in the number of women walking through the Welcome Centre’s doors, but also a 54 per cent increase in the length of the average stay for each family, and a 40 per cent increase in the length of stay for single people.

“We’re seeing more people, but we’re also seeing longer stays. So that then inhibits my ability as a shelter provider to turn over those beds,” Laforet said.

“Women are staying in shelter much longer because they really have nowhere else to transition to,” adds Laurie Hepburn, who runs Halton Women’s Place.

“The lack of affordable and supportive housing means that emergency shelters are becoming de facto long-term housing.”

Hepburn said wait lists for housing are getting longer, even priority lists for women experiencing domestic violence. Halton Women’s Place has partnered with Habitat for Humanity to access short-term transitional housing units for clients leaving their shelter.

Given its proximity to Toronto, Hepburn said very few of the women leaving Halton Women’s Place are getting housing in the region. Many are transitioned out of the local area and into other parts of the province where more is available.

According to the City of Toronto, the average wait-time for a studio apartment is between nine and 11 years, while it jumps to 15 years for a one-bedroom apartment. In Ottawa, wait times for social housing are up to five years.

Passing the buck

Ontario is the only province in Canada that has passed responsibility for housing and homelessness down to municipal governments. The change occurred over the course of a few years, with the 2011 Ontario Housing Services Act finally making municipalities responsible for the administration and funding of all types of social and supportive housing.

There are now 47 service managers across the province delivering core services for people experiencing homelessness.

With the exception of the cities of Toronto, Greater Sudbury, and Ottawa, which each have their own services, the other service managers encompass smaller cities, townships, and municipalities within their remit. District services serve communities in northern Ontario.

Each service manager provided data for the AMO’s homelessness research. Collectively, they reported just over 27,000 housing spaces on offer, two-thirds of which are emergency shelter spaces.

The report also concluded that “supportive housing—proven to help people transition out of homelessness permanently— is in critically short supply.”

“Our municipalities don’t have that kind of funding,” said Renee Geniole, executive director at Reach Out Chatham-Kent (R.O.C.K.). “They’re stretching pennies like crazy.”

R.O.C.K’s client numbers more than doubled between 2019 and the most recent count. The rural nature of Chatham-Kent, which encompasses a number of small towns and villages, means that it’s rarely prioritized in outreach and harm reduction work, Geniole said.

Social services often go to the “bigger centres,” she said.

The provincial government’s most recent data shows that $5 billion was spent on housing and homelessness services between 2017 and 2018, including funding from the federal, provincial and municipal sources.

Between 2014-15 and 2017-18, municipalities funded more than half of community housing projects, with a third coming from the federal government.

Over that same time period, the provincial government funded nearly 70 per cent of all homelessness programs across Ontario, and almost all supportive housing programs. The chart below shoes total spending by each level of government in a four-year period, which is the most recent available data.

For people experiencing chronic homelessness, supplementary programs included in supportive housing are crucial to breaking the cycle, said Margery Muharrem, an outreach coordinator at R.O.C.K.

“You can’t give someone four walls and a roof and say: ‘Get on with it’,” Muharrem said, adding that they may not have the skills to live or look after a home independently.

AMO and Helpseeker Technologies’ modelling shows that ending chronic homelessness would require an $11 billion investment over the next decade and the development of more than 75,000 housing units.

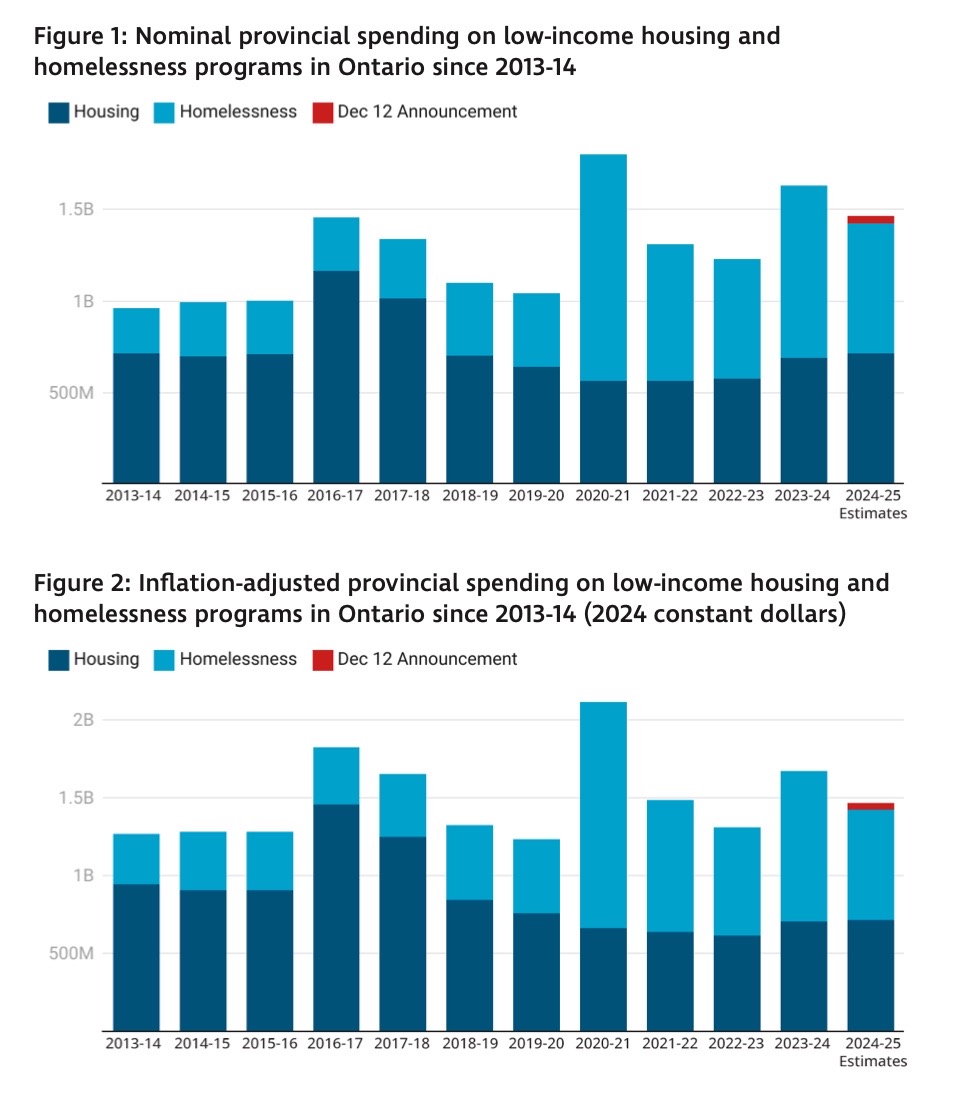

However, according to Maytree, a human rights organization, provincial spending on housing and homelessness has stagnated, despite increased need. While there was an uptick during COVID, funding decreased to pre-pandemic levels in 2021-2022.

“The data shows that, after adjusting for inflation, provincial spending is more or less where it was a decade ago. Projected spending in 2024-25 is slightly below the real average annual spending since 2013-14,” wrote Alexi White, director of systems change at Maytree.

White also found that “between 2016 and 2024, Ontario municipalities more than doubled their annual spending on housing … and more than tripled their spending on homelessness.”

Non-profits stuck in funding conundrum

At the end of 2024, a group of Ontario mayors asked Premier Doug Ford to invoke the Charter of Rights and Freedoms’ notwithstanding clause to allow them to clear encampments in their communities.

Not long after, the province announced an investment of $75.5 million in “homelessness prevention,” pledging to “take action to end encampments and crack down on public use of illegal drugs.”

Whether provincially or municipally funded, shelters and homelessness support services work very closely with the government. At R.O.C.K, staff saw the mayors’ request as a “political move that backfired on them.”

Windsor’s mayor participated in the campaign, asking Premier Ford for more powers in dismantling encampments. Laforet said the move was demoralizing for many frontline staff.

“At the end of the day, that speaks volumes about where that partnership is at,” she said

“I will say that the departments we work with at the municipality—housing, children’s services and departments solely responding to homelessness—we work amazingly well with, but there is still 100 per cent a disconnect between the understanding of what is needed to solve the problems and what those problems are.”

“Perhaps we have a different vision on that.”

Most of Welcome Centre’s funding comes from the provincial government, but Laforet is looking to diversify.

“If there were to be a large change to that core funding that we get, that would have the ability to decimate our services,” she said. “It makes it difficult to feel like you’re rowing in the same direction [as the provincial government].”

Not far from the Welcome Centre, Sylvie Guenther runs Hiatus House, another shelter and support centre for women and children in abusive households. Largely funded through Ontario’s Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services, Hiatus House is also ramping up fundraising efforts.

Provincial funding doesn’t stretch far enough, Guenther said.

Hiatus House was eligible for provincial funding set aside for victims of gender-based violence, but not for housing and homelessness funds.

Guenther and her team are also part of a group asking the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Rapid Housing Initiative to build 40 transitional housing units in Windsor. As it stands, women discharged from Hiatus House often return to a state of homelessness because there’s nowhere for them to go.

In addition to their federal applications, Guenther is also seeking funding from provincial, municipal, and private sources, such as foundations.

Providing a “continuum of care”

“Homelessness and shelters become a catch-all for gaps and holes in other systems,” Laforet said, noting a particular increase in seniors on fixed incomes who become unhoused after leaving hospital, and queer youth coming out to their parents.

Most shelters and organizations serving the unhoused provide a plethora of supplemental services. Hiatus House, for example, provides access to therapy, as well as support for those going through court and judicial processes.

At Start Me Up Niagara, Dumas and her team offer meals, washrooms, medical support, and mental health counselling, alongside art and recreational programs. They also provide donated clothing and hygiene products, and hope to launch a subsidized grocery store.

Meanwhile, Halton Women’s Place is trying to expand its transitional housing program to include a 12-month rental supplement for women who are looking for housing.