Exclusive: Dozens of grassroots groups cut off from funding after Ontario Trillium Foundation repealed ‘shared platform’ policy

Why It Matters

Recent changes in federal law have made it easier for foundations to grant to grassroots organizations. But some Ontario charities say policy changes made by the Ontario Trillium Foundation in 2020 move the province in the opposite direction, making it tougher for grassroots groups to access funds.

A record $601 million in provincial funding has flowed to the Ontario Trillium foundation over the last four years, but some charities and grassroots groups say the repeal of the foundation’s shared platform policy has meant they’ve been left behind and forced to find new funding partners.

As the pandemic unfolded in early 2020, the Ontario Trillium Foundation’s board passed a number of policy changes, including alterations to the foundation’s policies around shared platforms. Over the last three years, this change has blocked dozens of grassroots organizations from accessing foundation support. But exactly why this policy change was made remains unclear.

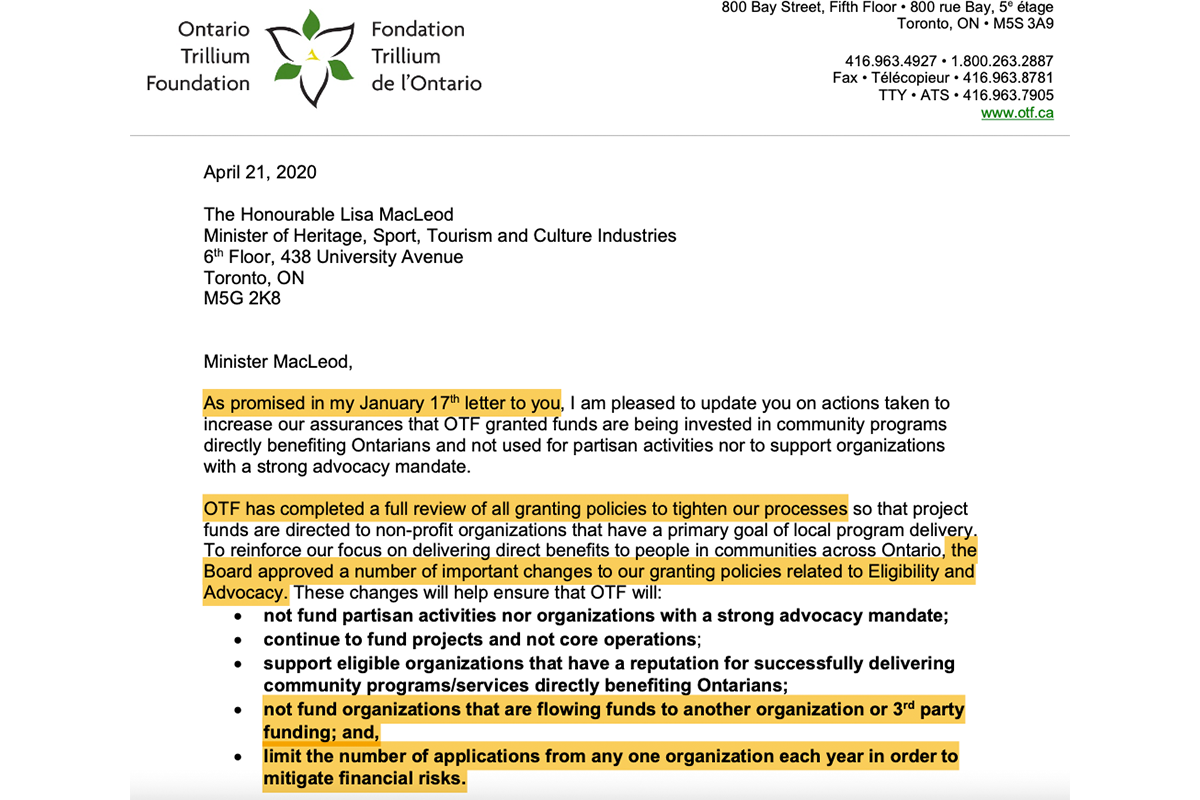

A letter sent by Trillium Foundation CEO Katharine Bambrick to Lisa MacLeod in 2020 — then Tourism, Culture and Sport Minister — suggests the repeal of the foundation’s shared platform policy was made to “mitigate financial risks.”

But staff from several charities operating shared platforms, which provide back-office and grant application support for grassroots groups, say the policy change harms their grassroots partners — many of which are led by Black, Indigenous and racialized staff and volunteers — by cutting them off from access to the foundation’s funding.

They add that Trillium’s policy change is out of step with broader trends in the charitable sector, which aim to simplify grant access for grassroots organizations and say they want Trillium’s board to reinstate the old policy to make the process fairer for all applicants.

Previous policy said shared platforms helped OTF “maximize impact”

In 2015, Toronto-based Not Far From The Tree received $58,300 from the Ontario Trillium Foundation. The money helped them divert hundreds of pounds of fresh fruit from local landfills, putting it into the hands of residents, food banks and local food programs instead.

Food insecurity, exacerbated by high inflation and wage stagnation, has only increased over the last eight years. But Julia Girmenia, the organization’s director, says the foundation’s shared platform policy change has put similar funds out of reach, limiting the organization’s capacity to expand.

“We don’t want to fill the landfill with this fruit when there’s a huge food insecurity crisis in our city,” she says. “But with a team of two, we are pretty limited in how much ground we can cover.”

Girmenia says the problem stems from the foundation’s stance on Not Far From The Tree’s governance model, which is predominantly volunteer-led.

Their signature program engages volunteers to pick fruit from vines, bushes and trees in hundreds of yards across the city. Apples, pears and grapes in hand, the bounty is split equally between homeowners, volunteer pickers and local social service organizations.

In the early days, Not Far From The Tree’s volunteer board opted not to incorporate the organization as a charity — a process that can take more than six months and cost up to $15,000 in legal fees. Instead, they joined the MakeWay Foundation’s shared platform.

This allowed the grassroots organization to access a host of shared resources from MakeWay, including legal services, accounting, fundraising and human resources support. Accessing these services independently through consulting firms would have been cost-prohibitive, says Girmenia.

The MakeWay Foundation’s shared platform also gave Not Far From the Tree the ability to offer tax-receipts to donors who direct gifts to the grassroots organization — something that can incentivize additional donations.

To fund this hosting service, MakeWay and similar organizations typically collect a fee equaling 10 to 15 per cent of a project’s annual revenue. They also assume all legal and financial responsibilities for projects, which must operate in alignment with their own mission.

Prior to 2020, the Ontario Trillium Foundation welcomed this arrangement.

The foundation’s 2017 collaborative applicants policy says shared platforms were eligible for funds, calling them an “important part of the collaborative spectrum.” Working with shared platforms allowed the foundation to “maximize” its impact, reads the policy.

This open stance was reflected in MakeWay’s grant application success.

Between 2015 and 2019, the national public foundation secured between two and seven grants per year from the Trillium Foundation on behalf of 20-odd Ontario-based shared platform projects. Grants ranged from three to 60 months in length and were valued between roughly $16,000 and $1 million. They focused on everything from food insecurity to Indigenous sovereignty.

But their success came to an abrupt end.

In 2020, after Trillium’s board changed their collaboration policy, foundation staff told MakeWay and other shared platforms they’d be limited to submitting just one application per grant cycle — be it an application for funds for their own charity or a shared platform project.

Not Far From The Tree and their 20-odd shared platform project counterparts now had to compete to be selected by MakeWay to have their application submitted to OTF.

Lizzie Howells, shared platform director for MakeWay says the policy change was “incredibly difficult” and came early in the pandemic, just when grassroots organizations needed provincial funds the most.

Future of Good asked Trillium’s CEO Katharine Bambrick for an interview to discuss the policy changes, but she declined through the organization’s director of communications, Marzeno Gersho.

By email, Gersho says the foundation updates its policies “to ensure clarity and understanding by applicants as well as develop new policies that meet OTF’s granting objectives.”

She says the one application per granting stream policy was developed “to ensure competitive fairness, avoid dependency on OTF funding, ensure capacity to manage OTF funds, mitigate risk, and ensure equitable access for a broad range of applicants.”

Girmenia is puzzled by this explanation.

“I don’t think it’s really being inclusive,” she says. “We should all have the same opportunity to shoot our shot.”

Policy change comes following meeting with Minister: FOI documents show

Documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request show changes to the foundation’s shared platform policy were made to align with direction from Trillium’s board and the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport.

On January 17, 2020 — three months before the shared platform policy was repealed — Bambrick sent a letter to Minister MacLeod thanking her for meeting with foundation staff in the days prior. She added the Trillium Foundation had set a “full review” of its policies in motion to ensure granted funds were invested in community programs directly benefiting Ontarians and not supporting organizations with a “strong advocacy mandate.”

In the weeks following, the policy committee of OTF’s board of directors met a number of times to discuss updates to the foundation’s shared platform and advocacy policies. A briefing note prepared for a meeting of that committee on February 3, 2020 says a key goal of the policy update was to provide “clear messaging” and to ensure the foundation’s policies align with “government and board direction.”

While the briefing note focuses on the changes to the foundation’s advocacy policies, it adds that planned “revisions” to OTF’s collaborative policy, which deals with shared platforms, will impact “stakeholder messaging and process” — in particular those linked with the foundation’s youth opportunities fund, which relies heavily on trustee relationships.

On March 12, 2020, the board approved changes to the foundation’s collaborative policy, repealing its previous support for shared platforms and creating a new one application per deadline policy, now known as the one application per granting stream deadline policy.

Roughly five weeks later, Bambrick sent a second letter to MacLeod — the one suggesting its shared platform policy was repealed to mitigate financial risks.

“OTF has completed a full review of all granting policies to tighten our processes,” the letter goes on to say. “These changes will help ensure that OTF will…not fund organizations that are flowing funds to another organization…[and will] limit the number of applications from any one organization each year in order to mitigate financial risks.”

In the following months, executives operating shared platforms in Ontario learned of Trillium’s policy change. Concerned, a group sent a joint letter to MacLeod and Trillium’s board chair Michael Diamond on November 24, 2020, asking for a meeting and for a policy reversal.

In the letter, they stressed the “harm” this new policy would cause the Black, Indigenous and youth-led organizations that formed the bulk of the organization’s trusteed groups. They also said the issue was particularly urgent given the new two-year $100 million community building fund the government announced just weeks prior to support non-profit organizations in their pandemic recovery.

Bambrick agreed to a video call with the letter’s signatories, but the former executive director of one organization who attended the meeting believes it was clear from the CEO’s tone that the policy wouldn’t be reversed. “I felt like it was strictly an appeasement [meeting],” she says. “They weren’t taking it seriously. They were just trying to calm us down.”

Referencing the letter Bambrick sent to MacLeod in March 2020, Future of Good asked Marzena Gersho what “financial risks” the minister or OTF believed shared platforms pose. No response was received.

David Stevens, a lawyer with Gowling WLG who has experience with shared platforms, is sympathetic to the fiscal concern. The “relative looseness” of shared platforms can make it more difficult for funders to ensure their money is spent appropriately, he says.

But Girmenia and staff of other shared platforms disagree.

Are shared platforms riskier?

Girmenia meets with MakeWay staff weekly, presenting ample opportunity for the foundation to flag any issues with how her organization is spending grant funds, she says. “Without MakeWay, I could understand how Not Far From The Tree could be a risk to OTF,” she says. But under the oversight of the foundation, she can’t understand the logic.

Howell adds that MakeWay, as a shared platform provider, must exercise “direction and control” over the projects that operate on their platform.”. They must also observe the same Canada Revenue Agency-mandated rules as any other charity would follow. Although, in recent years, the direction and control regime has come under fire from many charities and foundations for being too accountability-focused and rigid.

“Really, what we’re offering is a way for groups to spend more time and money on the things that matter to communities to get them out in the field delivering programming,” she says.

Bibiana Virgüez, interim director of programs and advocacy for FoodShare, another organization operating a shared platform, also takes issue with Gersho’s assertion that Trillum’s one application per granting stream policy helps ensure “equitable access” to funding “for a broad range of applicants.”

Not so. For many applicants, particularly grassroots organizations predominantly led by Black, Indigenous and racialized folks, the policy change has reduced access to the foundation’s funds, Virgüez says. FoodShare created its shared platform about a decade ago with the aim of helping resource these sorts of grassroots food justice groups, she adds.

Rather than trying to be everywhere all at once, which Virgüez describes as a “colonial” approach, the shared platform model allows FoodShare to boost the capacity of other neighbourhood-based food justice organizations. It also allows FoodShare to pool knowledge around issues like tax navigation, benefitting a wider group of Toronto-based organizations.

Virgüez says her organization trusteed nine groups last year, including Black Creek Community Farm, Thorncliffe Park Urban Farmers and CaterToronto — all organizations led by staff and volunteers from under-served communities.

But since 2020, FoodShare has been unable to trustee any of their Trillium applications, because the charity has submitted applications for funds to support their own programs and infrastructure — and are limited to just one application per cycle, she says.

In effect, this policy change has “reinforced” funding systems which under-resource Black and Indigenous-led organizations, Virgüez says.

She acknowledges Trillium’s existing policy allows FoodShare’s projects to find other trustee organizations to steward Trillium grant applications or to collaborate with another charity on a joint project.

But Girmenia says doing so takes precious time and energy. “It’s like, ‘Okay, this is another piece to add to the list of a million things that a small grassroots organization has to do,’’’ she says.

Not all impacted by shared platform policy change equally

However, not all grassroots organizations have been equally affected by the policy change, according to the foundation’s grant funding database.

Several organizations operating shared platforms have received Trillium funding for multiple trusteed projects per grant cycle without issue since the 2020 policy change came into effect.

A shared platform manager for one such Toronto-based charity, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, says she was not aware of Trillium’s one application per granting stream deadline policy. Rather, she says, foundation staff have reached out to her organization asking if they’d be willing to serve as a so-called organizational mentor and trustee for multiple groups keen to apply for youth opportunities fund dollars.

In 2021, her charity received four Trillium Foundation grants: three grants on behalf of trusteed organizations through the youth opportunities fund and one grant for their own charity through the resilient communities fund.

Asked about this discrepancy, Gersho says the youth opportunities fund is a “very different program with very different needs” than the foundation’s other funds. She says that, through the youth opportunities fund’s organizational mentor program, trustee organizations provide guidance and support for grassroots groups with a “primary focus on delivering programming.”

But the executive director of another Toronto-based charity, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity, says Trillium’s policy is being applied unevenly.

Prior to 2020, this organization had considerable success supporting a dozen or so shared platform organizations in securing Trillium grants. Since the foundation’s board shifted policy, however, things are different.

According to the executive director, the organization recently applied for capacity building funds for their own charity, but was deemed ineligible by the foundation because they’d received one grant via the youth opportunities fund the previous year.

“I don’t understand how a policy doesn’t apply across the board, but it just applies to us,” the executive director says. “I feel like it’s very inequitable.”

Gersho recommends any organization with questions about eligibility book a one-on-one coaching call with a Trillium program manager.

But Virgüez says she doesn’t understand why trusteeship would be OK with the youth program and not with any of the foundation’s other grant streams. It’s not just youth-led organizations who can benefit from shared platform support, she adds.

“I recognize that supporting youth [grantees] is important, but I can’t understand why you cannot do the same with BIPOC [grantees] if we know there is a gap in the system similar to youth,” she says.

Foundation is “going backwards”: Virgüez

Each year, Not Far From The Tree staff and volunteers hustle to raise their $300,000 budget to keep fresh fruit out of the landfill.

To do so, Girmenia says, they charge volunteer fruit pickers membership fees, host fee-for-service fruit picking outings with company teams and raise funds from private and corporate foundations. Since launching 14 years ago, their volunteers have picked over 250,000 pounds of fruit — an impressive feat — but less than a quarter of what’s produced by Toronto’s “urban orchard” every year.

With more money, Girmenia says her organization could scale up and divert more pears, apples and cherries from landfills to food banks. They could also expand the program to other municipalities.

Before the policy change, Girmenia says funding from the Ontario Trillium Foundation was very competitive, but nonetheless, they had a clear path to apply. Now, things are tougher.

Howells and Virgüez say they want Trillium’s board to reinstate the foundation’s old shared platform policy, which would be in step with broader shifts in the grantmaking sector aimed at increasing grassroots organizations’ access to grants.

In June, the federal government changed the law making it possible for foundations to grant directly to non-charities, also known as non-qualified donees, without oversight from a charitable trustee. A variety of other funders have also welcomed applications from non-charities, including the City of Toronto, the United Way, and several family foundations.

“Right now, everybody is talking about sovereignty,” Virgüez says. “[But] it kind of seems like [the Ontario Trillium Foundation] is going backwards.”