From spam bots to doxxing, cyberbullying is bringing non-profits to their knees. What can be done?

Why It Matters

There is little criminal and legal protection for staff members who are targeted personally by cyberbullies - many of whom also identify as being part of the same marginalized communities they work with.

They were ready. They launched. Then, the bots swarmed everything.

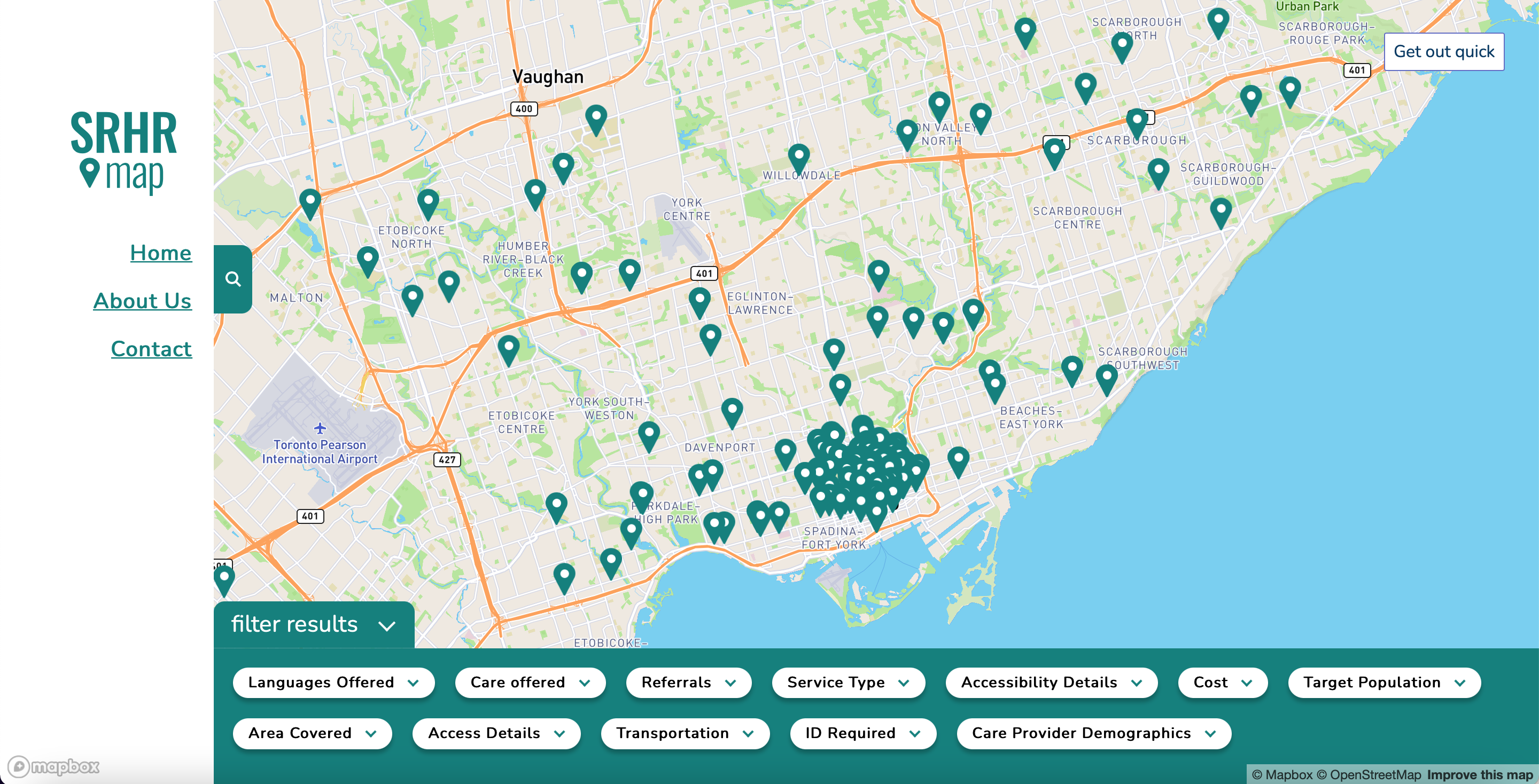

When SRHR Hubs launched its first virtual map of sexual and reproductive services across Canada, there was a lot of excitement about the project, recalled Rae Jardine, founder and executive director.

“We had lots of dreams about what we could create,” they said. “This was our biggest visionary project.”

Later, when recruiting people to help build digital features into the map, Jardine and their team noticed suspicious registrations.

Not only were there fake-sounding names filling in online forms, but several generic emails popped up in their inbox. While the content of the emails wasn’t alarming, the volume certainly was, Jardine said.

“Our forms were swamped because there were so many people answering,” they said. “We started putting in security features: geolocation to participate in Canada, captchas, cookie links.

“We were throwing everything we could at the problem.”

It wasn’t long before the bot spam spread to the SRHR Hubs’ email inbox and other facets of their programming. Jardine realized that it wasn’t humans spawning this content but anonymous bots directed to their site.

The generic names were one giveaway. The other was the speed at which forms were being filled in – impossible for human users.

The bots eventually came for the surveys that SRHR Hubs had sent out about their programs, making it increasingly difficult to discern real responses from fake ones. Every feature on the map—such as adding a new sexual or reproductive health service, requesting changes, or providing feedback—was disabled, and the team had to switch to using PDF forms, increasing their workload.

Jardine spent a lot of time on customer service helplines trying to recover their forms.

“To this day, we have no idea who it was, but we have our suspicions,” they said.

“A little prior, we had done some work on abortion rights – we think that is possibly something people could not have liked and attacked us for. It’s not a random attack.”

Jardine expressed particular disappointment with funders, who were unwilling to help. Cybersecurity is not a budget line that organizations often preemptively plan for, they added.

“This is a large-scale setback to this project, and it is still on hold. We are not where we’re supposed to be on our project timeline.

“This experience has left us in fear. Every time we do a virtual callout, we’re on edge.”

2SLGBTQIA+ organizations particularly at risk

Ultimately, Jardine describes the experience as chaotic.

“Our space is hard to work in – we’re dealing with funding insecurity and uncompensated labour. It became detrimental to team morale and mental health.”

Although the SRHR Hubs team was not at personal risk from this attack, it raised alarm bells about the potential of doxxing – the risk of hackers and cyberbullies publishing personal, identifiable information about an individual or staff member on the Internet.

When onboarding their latest board members, Jardine ensured they knew the risks.

“We wanted them to make an informed choice.”

Working in the sexual and reproductive health space, Jardine has also heard rumblings of this affecting organizations in other sectors.

“We’re hearing more and more censorship of social justice content on platforms, coupled with less safeguarding,” they said.

“Anecdotally, we’re seeing much more homophobic and transphobic content – we’re having to shut down posts and comments.”

The Ontario Digital Literacy and Access Network (ODLAN) recently released The Internet Isn’t All Rainbows, a report outlining the experiences of 17 2SLGBTQIA+ organizations across Canada in being exposed to and mitigating queerphobic hate online.

The report was produced in partnership with Wisdom2Action, whose executive director, Fae Johnstone, received vast amounts of harassment online after featuring in a Hershey Canada campaign for International Women’s Day in 2023.

The report found that online hate can be directed at organizations as a whole and specific individuals who work in them, particularly those whose roles are more visible and prominent within the community.

Research participants not only reported experiencing this hate on their social media pages and in their email inboxes, but many also had bullies infiltrating virtual events.

One participant shared that ‘Zoom-bombing’ – the practice of infiltrating online meetings, public or closed, and disrupting them – and recording queer spaces have become common in the U.S. Some were also faced with threats that the online hate would continue to in-person violence.

LGBT Youthline offers confidential peer support to young people in the 2SLGBTQIA+ community. The people who volunteer to provide this peer support are often also queer youth.

At the end of last year, LGBT YouthLine received several calls from fake callers, seemingly to waste volunteers’ time, said Lauren Pragg, executive director.

The spike in fake phone calls was most noticeable between September and December when anti-trans protests erupted across the country.

“It’s difficult to know whether it was related to the anti-trans protests, but it’s a safe bet,” added Nur Ali, peer support manager.

View this post on Instagram

LGBT YouthLine staff and volunteers provide critical support to young people in the 2SLGBTQ+ community, but their call and text lines have recently become flooded with fake callers.

Like SRHR Hubs, LGBT YouthLine also found that sign-up forms were spammed by bots, which meant it felt unsafe to run in-person programming.

Both Pragg and Ali noted there is often a tension between limiting the organization’s exposure and ensuring that vulnerable youth know the service is out there.

“It’s a double-edged sword – we would like to do advocacy, but it can also draw unwanted attention. What is the balance between us doing communications work and trying to protect our volunteers?”

Political changes cited as possible causes

Like LGBT YouthLine, participants in ODLAN’s research “noted that queerphobic online hate is tied to and influenced by far-right politics. One participant in the BIPOC session said, ‘The far right seems to have shifted their attention from anti-vax, COVID kind of angst, to all of a sudden it’s the queer community that is responsible for the unravelling fabric of society.’”

The Whitby Public Library noted a “shift in discourse” in 2022, which affected their Drag Queen Storytime (DQST) program.

Other libraries continue to be targeted for similar events, with Thunder Bay Public Library reporting a bomb threat during their scheduled drag story time event just last month.

In Whitby, where the program has been running since 2019, the public library received complaints from those outside the community and the U.S.

“In the weeks leading up to the 2022 event, there was widespread misinformation, which resulted in a large increase in questions for our staff,” said Jaclyn Derlatka, manager of strategic initiatives at Whitby Public Library.

“The vast majority of our community members were supportive, but there was a vocal minority that disagreed with the library hosting DQST. Some told our staff they were going to complain to the Mayor about the program, while others simply asked why the event was being held,” Derlatka said.

Complaints decreased in 2023, and the Whitby Public Library team even won an award for hosting the event. But 2022 was still a challenging year for staff.

“It’s never easy dealing with anger and misinformation,” Derlatka said.

“We also learned a great deal about protest management, which is not a typical issue for public libraries to familiarize themselves with.”

Anti-trans rhetoric from politicians also affected the team at Leadnow, said senior campaigner Nayeli Jimenez. Leadnow is a multi-issue advocacy and campaigning organization, and that sometimes means that community members and donors who feel strongly about one issue may not be aligned in their perspectives about another issue – for example, there may be a strong cohort who feel strongly about economic justice, who may not be aligned with Leadnow on their climate change advocacy, said executive director Shanaaz Gokool.

“Sometimes there is a tendency to talk about the Leadnow community, but in reality, it’s communities within communities within our larger email list,” Gokool added.

At Leadnow, the team often receives messages from their community directly into their personal inboxes rather than the general email inbox – which can have positive and negative consequences. Gokool has also been targeted and stalked on LinkedIn and Jiminez on X – both of them acknowledge that women of colour are often the targets of online abuse.

“When I get those LinkedIn messages, I think to myself that it’s not my responsibility to fix somebody else’s hate,” Gokool said.

Lack of legal protections and safeguarding on platforms

For the Whitby Public Library team, when messages crossed a line into harassment and hate, they could report to the Durham Region Police Service.

However, as ODLAN’s report notes, many organizations may feel hesitant about contacting the police, particularly those where staff and community members belong to marginalized groups.

Jardine, for example, didn’t report the SRHR Hubs case to the police. “The laws are still catching up to the intricacies,” they said.

While cyberbullying is not explicitly covered under the Criminal Code, behaviour that could be interpreted as harassment, threats, intimidation, defamation, attacks on people or property, and incitement of hatred is.

Perpetrators can be taken to court – if the organization or individual on the receiving end can even find out who they are. In cyberspaces, perpetrators can hide behind usernames that are difficult to track down.

“At the moment, hate content is very narrowly defined in the Criminal Code of Canada, which means charges are rare,” said Tricia Grant, director of marketing and communications at MediaSmarts, an organization dedicated to increasing digital literacy in Canada.

“The Online Harms Bill may also have implications for how online hate is defined and addressed legally, should it come into effect.”

The Online Harms Bill seeks to hold platforms accountable when filtering hateful and harmful content. The Bill is primarily focused on protecting and safeguarding children, but there is a proposed Digital Safety Commission and Ombudsperson that would “advocate for the public interest with respect to systemic issues related to online safety.”

Organizations usually set aside $100,000 for legal battles, said Warda Youssouf, the founder of the grassroots community House of Arts Toronto. But as an organization run by one person, this wasn’t an option available to her when she fell victim to a cyberbullying attack earlier this year.

“Someone is spreading false information about me online and engaging in cyberbullying activities,” Youssouf wrote on Instagram.

“House of Arts will be taking a temporary hiatus for the rest of the month to address the pressing legal issue related to cyberbullying, and to prioritize my mental health and wellbeing.”

Youssouf had to cancel gatherings for artists and creatives while she recovered.

View this post on Instagram

When these attacks began, Youssouf was already feeling depleted, she said. She hadn’t been able to apply for grants, and she often found that she was working for free herself.

Newcomers that she had employed had to stop working for House of Arts. The attacker not only messaged Youssouf’s social media accounts but also contacted organizations she had previously worked with.

“I am not registered – House of Arts is all grassroots,” she said. She eventually received support from Toronto-based VIBE Arts, which was running legal clinics and consultations at the time.

Non-profits investing more in wellbeing and mental health support – but is that enough?

Content moderation can take a toll on staff morale, Grant said, especially if they are directly affected by hateful messages or being contacted personally.

“Safeguards should be put into place for people who take on a content moderation role, including ensuring team members have access to mental health supports, are able to take breaks from this task, and ideally given a separate device from their own personal device to do this work,” she said.

Recognizing that volunteers are critical to the organization, YouthLine had to rethink its policies and procedures to safeguard them as much as possible.

YouthLine’s volunteer peer supporters are provided with a script if they encounter a caller who uses homophobic or transphobic language.

“Our shift supervisors can see every chat as it unfolds in the back end. We can pre-empt issues and take them over or ask other volunteers to take it on. We do immediate debriefs and ask people if they would like to end their shifts,” Ali said.

At Leadnow, the team allocates the work of responding to or blocking cyberbullies to those not personally affected by the hateful comments, to avoid re-traumatizing staff.

In practice, that means that white team members are the ones dealing with racially motivated hate and cyberbullying in the organization’s email inbox or social media, for example.

Meta’s social media platforms also allow users to filter out and block certain words, but those comments may still be visible to the public and community members, Jimenez said.

“Unfortunately, I think a lot of us have been doing this work for so many years, even outside of Leadnow, in a way where we’re used to it, and we almost have our own personal ways of handling it, blocking people and knowing boundaries,” she added.

Gokool recommends that staff keep aggressive emails rather than delete them. The emails don’t need a response, but they may be needed in the future.

However, despite collecting the evidence, Gokool said many organizations may not know where to go or who to report to.

“Outside of direct threats to a person’s life, which is something enforceable, there are a lot of other messages that we get, there is no other place to go with.”

“I think one of the biggest issues is that no one really understands the scope,” Gokool continued.

“We understand silencing on Meta; we know that there is a lot of intimidation, bullying and outright harassment on X; we’ve seen the emails that come in – but there isn’t a place for us and other groups to say this is happening.

“I see it as a real failure of leadership. There is no oversight for the sector. There is no protection for us.”

In the absence of that oversight, employers should consider how to handle the aftereffects of bullying, according to Pen America.

Pen America has an Online Harassment Field Manual where they recommend different resources for non-profits and corporations who are dealing with anonymous attacks.

Employers and managers should hold private check-ins and health checks during meetings to ensure employees’ support and offer extra help when needed, according to their guide.

“As an individual, it can be difficult to get a platform’s attention, but organizations often have direct contacts at tech companies If an employee has reported abusive content that clearly violates a platform’s terms of service … escalating the issue directly with tech company contacts can make all the difference.”

In the meantime, employers should have policies in place to help with online abuse and an easy reporting tool, such as a Google form for employees.

They also recommend a workplace peer support group in the form of a Slack Channel or chat group so people can have a safe space to vent with others who may have gone through the same situation.

Gokool, Jardine and Pragg all called on funders and the non-profit sector to take a stance on cyberbullying.

“It’s hard for non-profits to keep up with the latest standards in security,” Pragg said, adding that additional funding and support on cybersecurity is critical in the age of AI.

“We are not shying away from integrating it into our advocacy work and pushing funders to have this in mind when making programming decisions and funding calls,” Jardine said.

“If the worst comes to pass, what kind of support are we getting from funders?”

Groups like the Canadian Centre for Nonprofit Digital Resilience are calling on funders to invest more in cybersecurity software, hardware and infrastructure, which very few philanthropic organizations are funding.

However, there is little that a funder or a non-profit can do to completely shield an organization from cyberbullying.

If the organization has a public presence on the Internet or social media platforms, it can be susceptible to harassment.

“Regardless of the policies we develop, my organization can’t stop me from being doxxed, my organization can’t stop me from receiving threats outside of work or on my personal, and even going private, they can … find ways sometimes to get at you,” said one respondent in ODLAN’s research.

“So I think part of it is [that] we need a larger systems change and accountability from social media platforms.”

Lauren Pragg was previously named as interim executive director. Their title has now been changed to executive director. LGBT Youthline was previously referred to as Youthline. The article has now been amended to reflect the correct name of the organization.