“This is groundbreaking information”: New report quantifies non-profit wage gaps

Why It Matters

Non-profits pay employees less and hire more women, immigrants and racialized people than other sectors of the economy. Knowing more about un-equitable compensation is key to improving working conditions and raising wages.

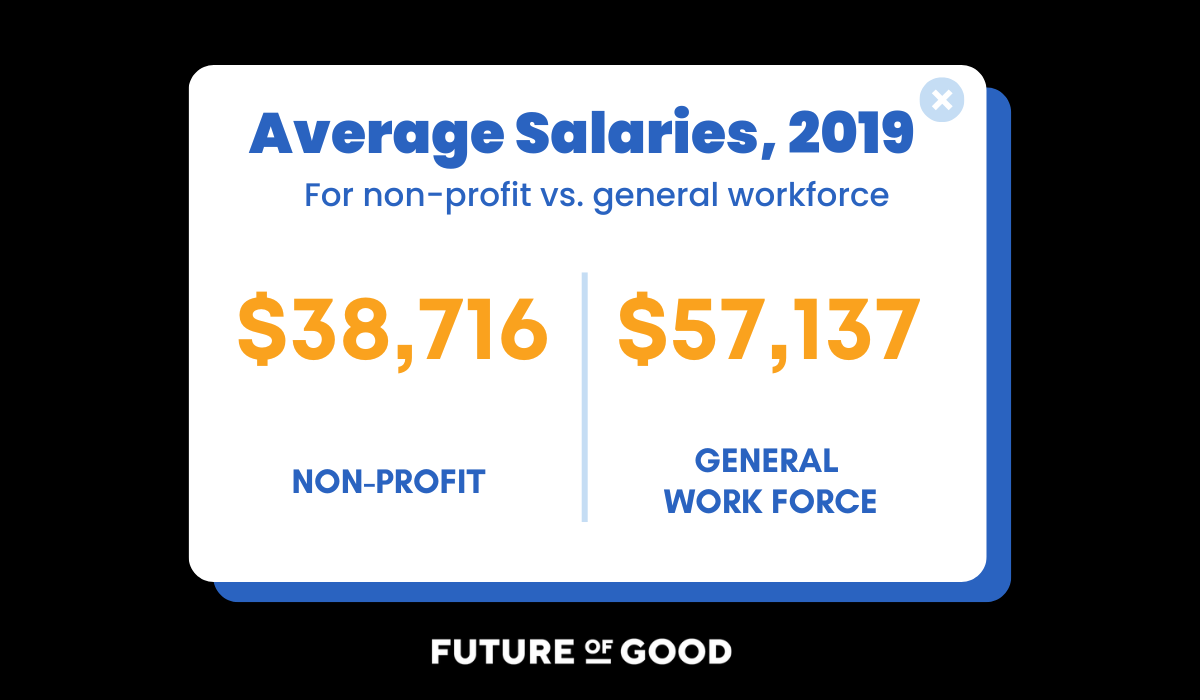

The average salary of an individual working at a community non-profit is more than $18,000 less than someone working in the overall economy, according to a new study released by Imagine Canada.

“When we saw the results, we were like ‘Oh my God, this is crazy. We have to get this out there,’” said Cathy Barr, Imagine Canada’s vice-president of research and strategy. “This is groundbreaking information.”

A detailed analysis of Statistics Canada data revealed that those working in the overall economy, excluding the self-employed, earned an average salary of $57,137 in 2019, while those employed by community non-profits — which provide goods and services like childcare, advocacy, access to the arts and social services — made an average of $38,716 per year.

The average salary at non-profit business organizations, such as chambers of commerce, condo boards or professional associations, and non-profit government organizations, like some residential care facilities, hospitals or post secondary institutions, was slightly higher, at $48,331 and $54,669 respectively.

“The pandemic has emphasized the importance of the non-profit sector’s work, but it has also laid bare the cracks in our operating environment,” wrote Emily Jensen, who authored the report. “Low-wage, low-benefit, short-term contract jobs are prevalent due to short-term, project-based funding.”

That underfunding, she goes on to write, often results in subpar working conditions and a dearth of professional development opportunities — something of particular concern, considering 77 per cent of all jobs at non-profits are held by women, while 47 per cent are filled by immigrants to Canada. Additionally, 29 per cent of non-profit employees are racialized individuals, compared to 20 per cent in the overall economy.

Barr said that, anecdotally, it’s long been known that women are over represented in the non-profit sector. However, this is the first time there’s been hard numbers to back that observation up.

“Only 12 per cent of jobs held by immigrant men are in the non-profit sector, but half of all jobs held by immigrant women are in the non-profit sector. That is astounding, right?” Barr said. “Think about what that means from a public policy perspective … half of the jobs for immigrant women are in the non-profit sector, and yet the governments treat us as, you know, unimportant, invisible, nice people doing nice things.”

Canada’s non-profits and charities employ 2.5 million people, representing 14 per cent of Canadian jobs. In 2019, approximately 660,000 of those workers were employed by community non-profits. The non-profit sector also contributes 8.3 per cent to gross domestic product, more than the construction, transportation, or agricultural sectors.

The report also found that those working at non-profits have higher levels of education than those working in for-profit industries, an observation made more impactful by the substantial wage disparity between the two.

Barr said that, by taking an intersectional approach to analysing Statistics Canada data, a clear picture of who is working at non-profits and how they’re being compensated is emerging for the first time. She hopes this will lead to better working conditions for those employed in the non-profit sector going forward.

“We’re a sector made up of women, immigrants and racialized people … who tend not to be taken seriously or given a lot of voice,” she said. “So, it’s almost like this report is, on some level, an answer to the question — why aren’t we taken seriously?”

Work done by racialized people, immigrants and women has historically been undervalued, particularly caregiving work, and that mentality continues to persist, Barr said.

Employment of racialized and immigrant workers in the sector is also rising quickly, according to the report’s author. Between 2010 and 2019, non-profit sector employment increased by 32 per cent for immigrants, compared with four per cent for other workers.

During that same period, employment of racialized individuals rose by 47 per cent, and the number of Black workers increased by 58 per cent, compared with a 6 per cent increase in non-racialized employees. Indigenous employment grew by 42 per cent.

The report also found that, across the sector, immigrant workers are paid more on average than non-immigrant workers.

“However, this data should be interpreted with several caveats. First, in much of the sector, racialized workers have lower salaries than other workers, which suggests that non-racialized immigrant workers are pushing up the average salary for all immigrant workers,” Jensen wrote. “Second, immigrant workers are overrepresented in the nursing field, which has higher wages than many other sector occupations.”

The data provided didn’t differentiate between recent and established immigrants who may have studied in Canada.

Going forward, Barr hopes funders move away from models that reinforce negative racialized and gendered stereotypes about the sector. She’d like to see more core and unrestricted funding opportunities, more flexibility and reduced application and reporting burdens.

The report also calls on federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments to treat the non-profit sector as a “valued partner on par with the way that other industries of similar size are treated.”

But the non-profit sector must also take a hard look at its own practices as well, if working conditions and wages are to improve, Barr said.

“We in the non-profit sector also need to also take this information onboard, and try harder, and do better,” she said. “I know non-profits are in a difficult situation, they don’t always have the money, but we’ve got to stop using that as an excuse to for exploiting workers.”